Van Gogh Museum Shows How Artists Present Themselves in Their Portraits

How do we picture ourselves? Now we take a selfie, in the past artists made a self-portrait. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is presenting its first exhibition focusing on artist’s portraits and tells stories about identity and image.

The majority of the nearly eighty works exhibited in In the Picture: Portraying the Artist belongs to the museum’s collection. Most on display date from roughly 1850 until 1920. On the exhibition’s second floor, grouped around themes like “the artist at work” or “the suffering artist”, visitors find works inspired by Vincent van Gogh’s self-portraits. These include art by Elin Danielson-Gambogi, Egon Schiele, Edvard Munch, James Ensor, Francis Bacon and many others.

The genre of artists' self-portraits increased in popularity

Why this focus on artists capturing themselves, or portraying their friends during this specific period? Curators Nienke Bakker and Lisa Smit explain that the genre of artists’ self-portraits increased in popularity. Artists could promote themselves through such portraits. Moreover, the interest in artists changed: who was the real person, the genius behind his or her art.

Of course, in this museum, any exhibition is linked to Van Gogh. About thirty years after his death, it was thought he had painted nearly fifty self-portraits. Over the years, with increasing knowledge and improving technical research, this number dropped. Of the remaining roughly twenty-five pictures, most were created while Van Gogh stayed with his brother Theo in Paris.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with grey felt hat, 1887

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with grey felt hat, 1887© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Why so many Parisian self-portraits? Van Gogh wanted to become a portrait painter but could not afford to pay models. The cheapest artist model is the artist. Or as he once wrote from Arles to Theo: ‘…I purposely bought a good enough mirror to work from myself, for want of a model…’ (Letters, 681)

Van Gogh’s poverty not only shows in self-portraits, many on a small scale. A few of his self-portraits were painted over by the artist, to save on the cost of canvas. Moreover, he also used cheap materials.

Take for instance his violets, created by mixing blue and red. After tests, some experts think the cheap red ingredient may have started to fade within weeks. What is now blue may well have started as a different colour.

In this exhibition, one self-portrait by Van Gogh seems unfinished. Research hints, Van Gogh’s self-portrait from 1887 may have looked totally different, once finished. As text next to it explains: at least one colour has disappeared. Did Van Gogh notice? His letters show he was not always pleased with his self-portraits. On the other hand: only two or perhaps four of the self-portraits may have actually been intended as such. The many unsigned ones Van Gogh used to experiment with styles and colours.

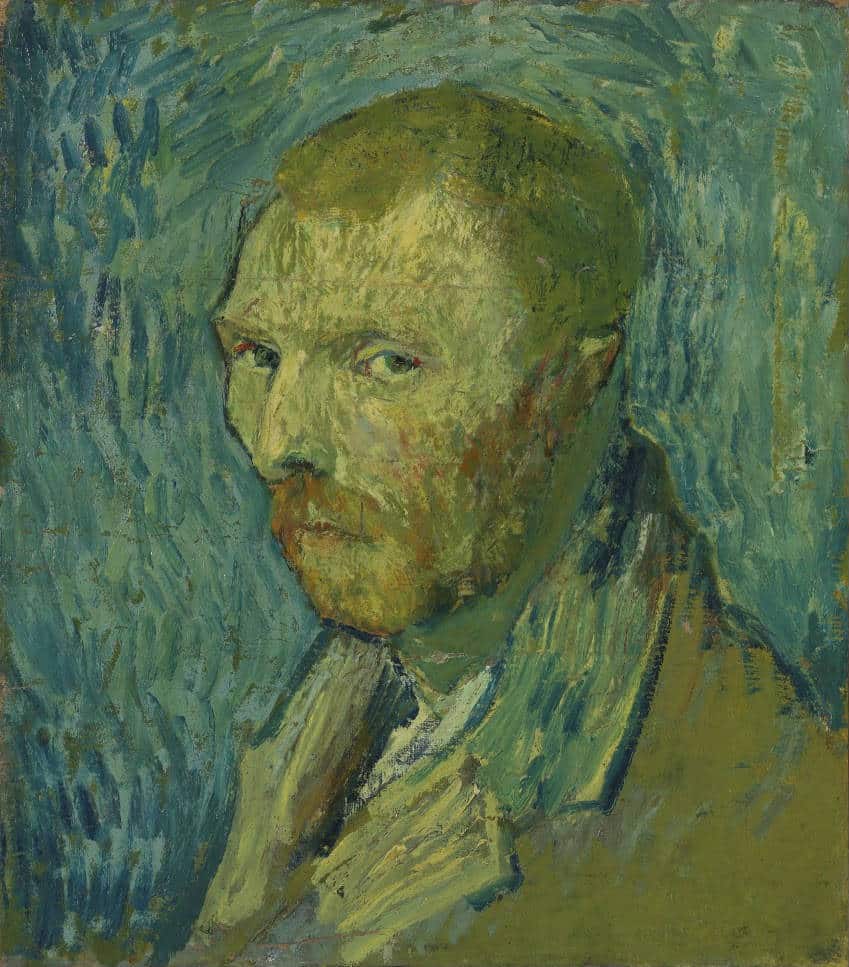

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889© Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo, photo by Anne Hansteen

On the ground floor of the museum, there is a spot where visitors can see several of Van Gogh’s self-portraits hanging in different parts of this exhibition with works grouped around themes. Comparing these, the different styles are obvious, yet they were created within roughly the same year. Van Gogh did not stop painting his portrait on moving to Arles, Saint-Rémy and Auvers-sur-Oise.

Before this exhibition opened, the Van Gogh Museum and Nasjonalmuseet in Oslo announced, extensive research had terminated a problem. The Norwegian museum owned a Van Gogh self-portrait after all, which of course is displayed in this exhibition. Experts now conclude that it was painted while Van Gogh was recovering from his first psychosis at the Saint-Rémy asylum, towards the end of August 1889.

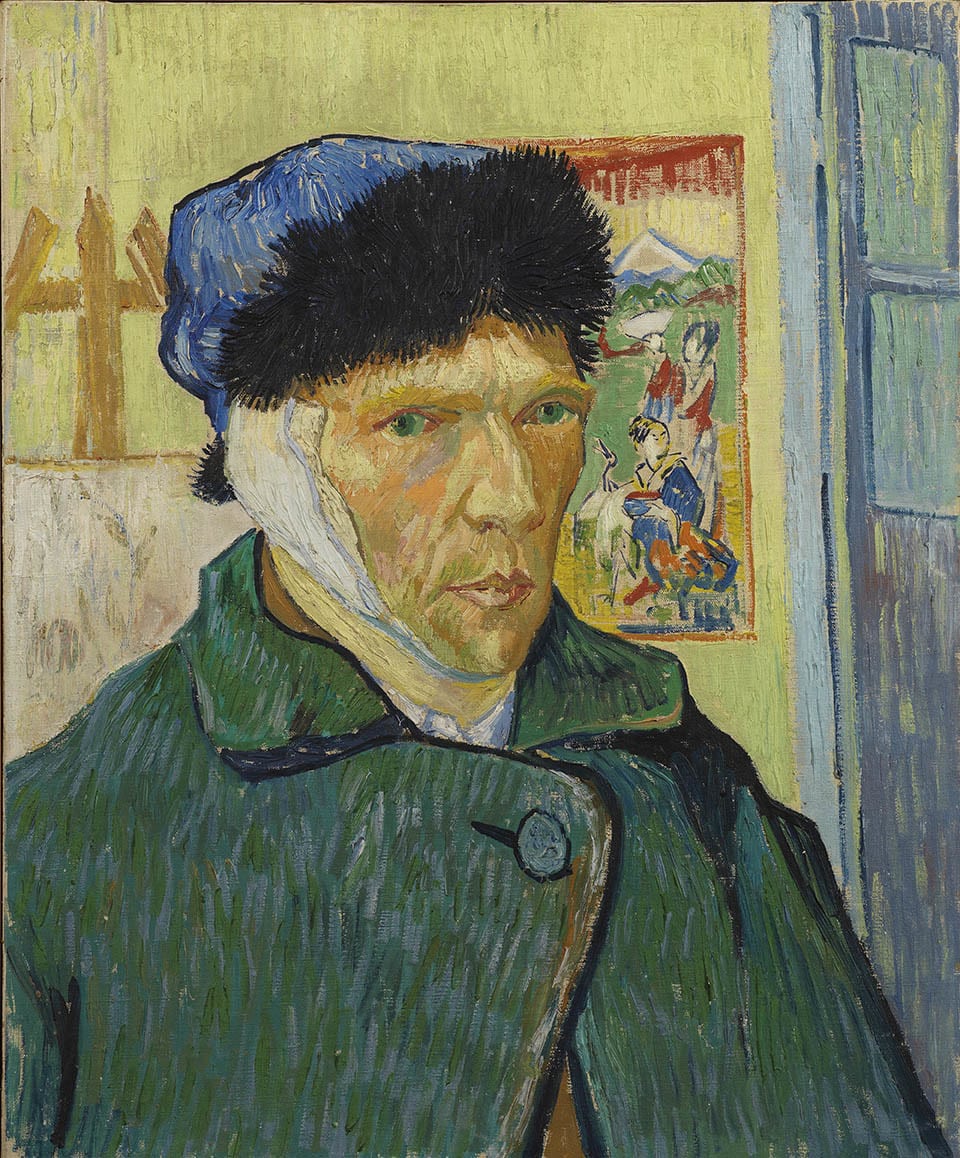

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, 1889© The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, Londen

This therapeutic work is not the only important self-portrait by Van Gogh in this exhibition. Also included is another iconic one. It is usually to be found at London’s Courtauld Gallery, which is currently closed. This famous self-portrait shows Van Gogh with bandaged ear (1889). Within the series of self-portraits, this is no experiment but a statement. Look carefully at the background, behind Van Gogh. On the left is a canvas on an easel and on the right a Japanese print. It implies that this artist may be suffering, but he continues to paint. As experts point out: ‘… [it] shows an artist both vulnerable and strong,… distressed, but … painting. The work provides insight into the identity, image, self-contemplation and suffering…’

John Russell, Vincent van Gogh, 1886

John Russell, Vincent van Gogh, 1886© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

In the Picture not only exhibits self-portraits, but it also contains wonderful portraits of artists painted by their friends, colleagues, rivals. Among these are several pictures of Van Gogh, including two which impressed me. Both portraits are displayed near Van Gogh’s self-portrait with a felt hat (1886 – 1887). One is by Australian artist John Russell and dates from 1886. It captures Van Gogh turning towards the viewer and seems a close resemblance. The other work dates from a year later. Using chalk and paper, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec captured a swift impression of his friend Van Gogh, sitting in at Café Le Tambourin, with a drink in front of him. Friends recalled, Van Gogh would storm in and down several drinks at the end of the day.

Do these works and his self-portraits show what Van Gogh looked like? We don’t know. He wrote that the self-portrait or portrait remained an important genre, but it was no longer important to capture an exact likeness. It was important to capture an impression of the real, living person – behind the mask.

Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum In the Picture: Portraying the Artist

runs until 30 Augustus 2020.