The Afterglow of the Van Gogh Comet

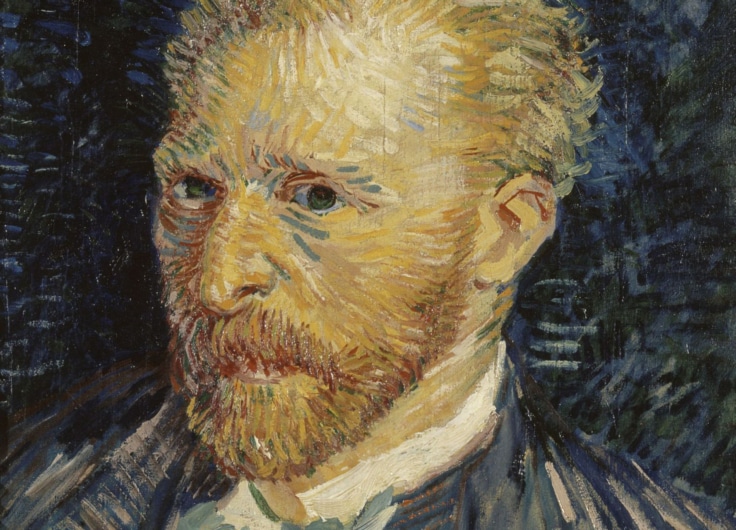

In a short life and an even shorter existence as an artist, Vincent van Gogh drew and painted an extensive oeuvre that pushed art history in new directions. The glow of the comet that was Van Gogh continues to twinkle, as is evident in three books that reveal new aspects of his life: his drawings studied in full context, the last months of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise, and his forgotten travels on foot through Belgium as a young man.

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) lived a whole life before taking up painting. He first worked as an art dealer, which ran in the family. He then tried his hand as a preacher, including in the Walloon mining region, which was another family tradition. He also had a few other small jobs in between these professions. In the summer of 1880, at the age of twenty-seven, he decided – as if it were a career choice – to become an artist himself. After ten years of intensive artistic activity, a tormented Van Gogh shot himself on the open ground behind the gardens of Château de Léry in Auvers-sur-Oise, an artist’s haven not far from Paris. He died there on July 29, 1890.

As an artist, Van Gogh was almost self-taught. After his “conversion” he educated himself using handbooks that taught him the grammar of painting. For a short while he studied at the art academies of Brussels and Antwerp and received some drawing and painting lessons from Anton Mauve, a relative and one of the painters of the Hague School. Van Gogh honoured him in 1888 with one of the flowering orchards he painted in Arles. Pink peach blossoms are depicted against a still frozen, winter ground form his painting Souvenir de Mauve.

Pink Peach Trees ('Souvenir de Mauve'), 1888

Pink Peach Trees ('Souvenir de Mauve'), 1888© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterloo

Theo van Gogh, himself active in the art trade, acted as a mentor and patron for his brother. On January 14th, 1882, shortly after Mauve’s lessons, Vincent wrote to Theo: “Drawing is becoming more and more of a passion for me, a passion just like a sailor has for the sea.”

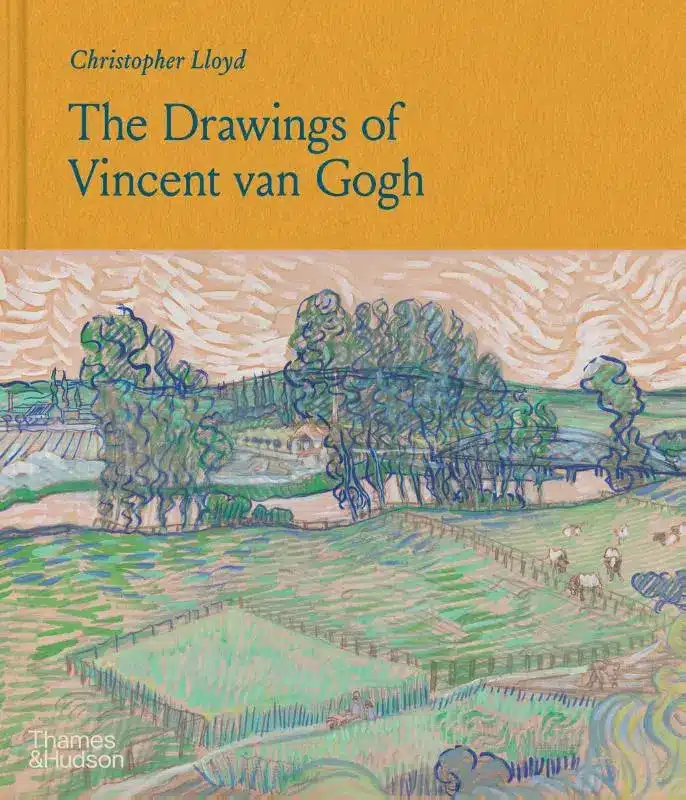

The Drawings of Vincent van Gogh, by the British art historian Christopher Lloyd, former curator of the British Royal Collection, is a book devoted to the passion that led Van Gogh to create more than a thousand drawings over his intense lifetime. Lloyd’s explanations for why Van Gogh’s drawings are so original are rooted in the artist’s unusual life path and the predominance of his talent and personality, rather than his craft and expertise. Van Gogh drew in his own way: “It is no exaggeration that he adapted almost all traditional drawing techniques, whether improvised or otherwise, and as a result, he became very aware of the visual impact and physical properties of pencil, pen, brush, ink, charcoal, chalk and watercolour”, Lloyd writes. Unhindered by traditions and conventions, Vincent experimented and combined techniques until he became Van Gogh.

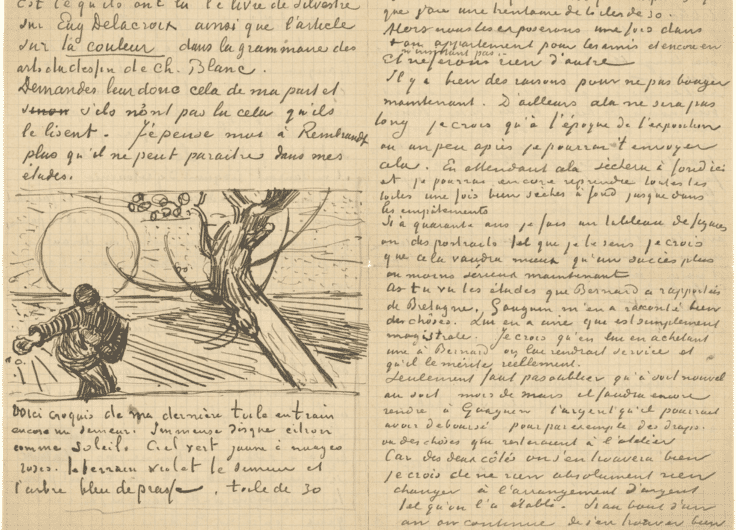

Lloyd’s book takes a cross-section of Van Gogh’s oeuvre based on technical characteristics – only his works on paper are included. It therefore contains all the drawings: loose sketches and preliminary studies, presentation drawings and detailed sketches of paintings, such as The Cafe Terrace on the Place du Forum in Arles at night, the painted version of which became an iconic Van Gogh painting. As well as these, the book also contains autonomous drawings that Van Gogh hoped to sell or publish as illustrations. As the chronology progresses and Van Gogh’s mastery grows, so does the virtuosity and complexity of his drawing. The book shows the stunning panoramic harvest scenes on the banks of the Rhône, which Van Gogh himself considered among his best drawings. The landscapes from Arles and Auvers-sur-Oise, captured with wavy and sometimes colourful lines, are often considered to be the most classic Van Goghs. Lloyd groups Van Gogh’s drawings into thematic clusters, each of which he discusses separately. The characters, the places, the landscapes, the portraits and the compositional drawings are discussed with attention to compositional aspects and technical features, as well as compared with older art (a Rembrandt and a Van Gogh are presented side by side). These thematic clusters are also biographically contextualised, and quotes from Vincent’s letters to Theo about the works are included too.

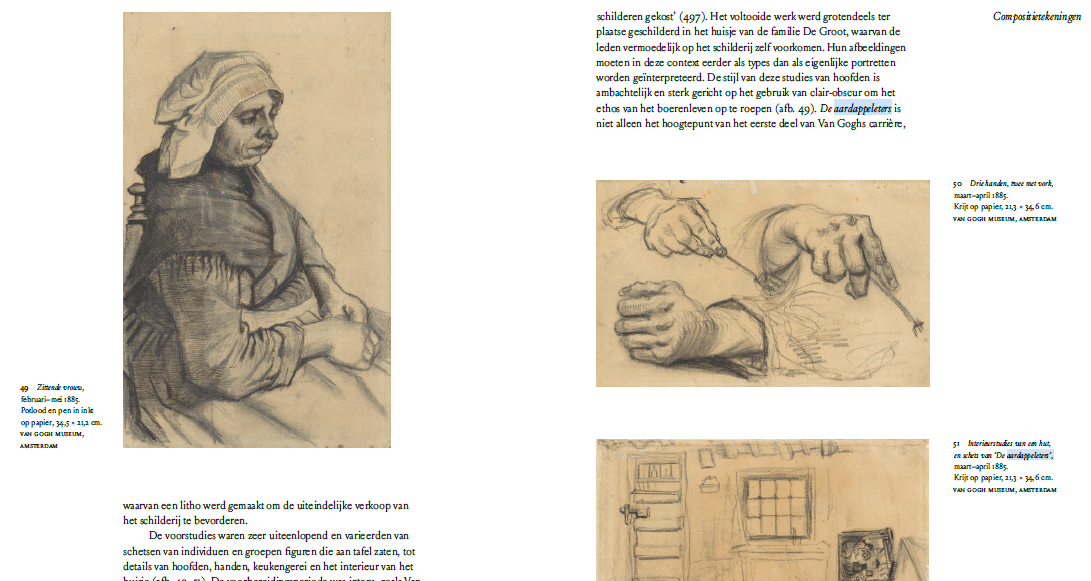

A page from ‘The drawings of Vincent van Gogh’ showing drawn preliminary studies for ‘The potato eaters’ (1886)

A page from ‘The drawings of Vincent van Gogh’ showing drawn preliminary studies for ‘The potato eaters’ (1886)© Mercatorfonds

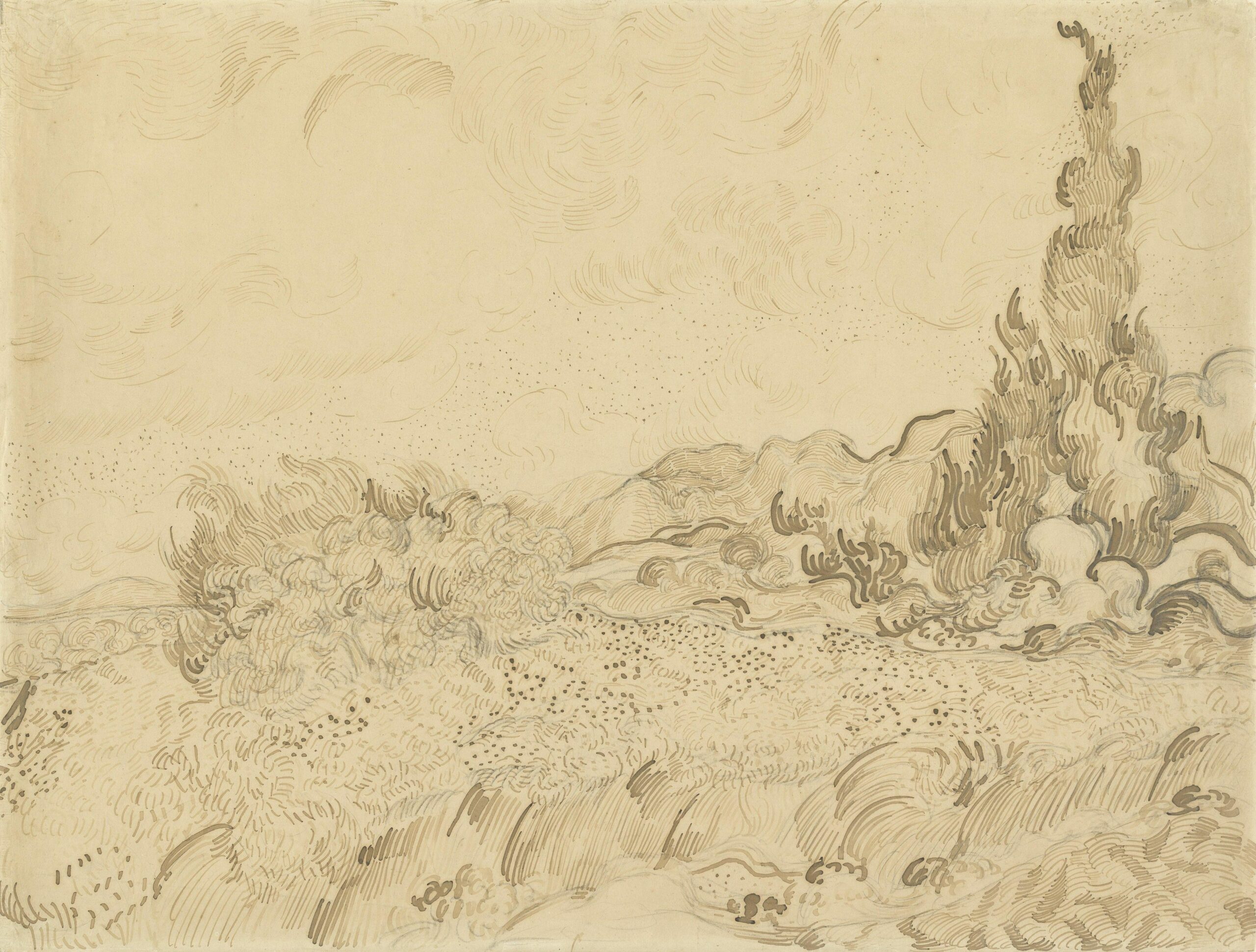

Lloyd’s book offers an insightful overview of Van Gogh’s drawing work, written with a sense of synthesis. It also shows the reader how Van Gogh’s art came into being. For example, extensive composition drawings weren’t a given due to financial limitations, which made the various preliminary studies for The Potato Eaters (1886) an investment – “a whole winter of painting heads & hands”, Vincent wrote to Theo. Biographical circumstances also had a major influence. After being admitted to a psychiatric hospital, the scope of Van Gogh’s work narrowed to the windows, corridors and rooms of an institution in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. But through those windows, Van Gogh was able to draw and paint Wheat Field with Cypresses (1889).

Wheat Field with Cypresses, Painting and drawing from 1889, created in a psychiatric institution in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence

Wheat Field with Cypresses, Painting and drawing from 1889, created in a psychiatric institution in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence © National Museum, Londen / Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

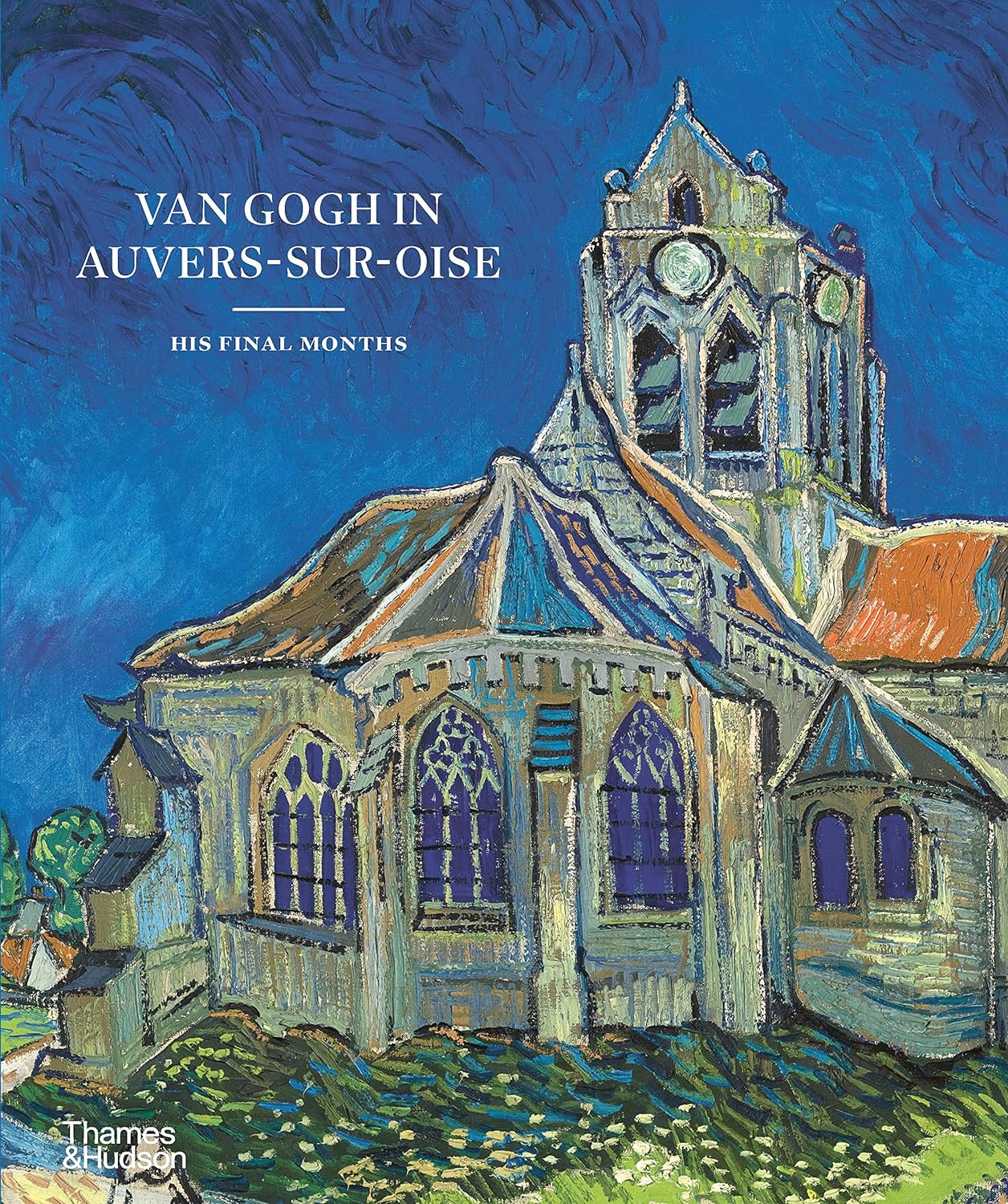

The Drawings of Vincent van Gogh was published by Thames & Hudson. Ghent publisher Tijdsbeeld, released Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise. His Final Months, the accompanying catalogue for the exhibition of the same name, was first shown in Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum in 2023 and then in Paris’ Musée d’Orsay until early 2024. Just like The Drawings, this book is also a feast for the eyes, and as an exhibition catalogue, it is exemplary. The authors, almost all of whom are affiliated with the Van Gogh Museum, succeed in giving their texts scientific merit without offending the reader. Much of the research is cleverly contained in references and footnotes and in the meticulously compiled index section, which fully maps Van Gogh’s production in Auvers-sur-Oise (seventy-four paintings and more than fifty drawings). All of this information is rock solid and does not hinder the beautiful pages where viewing is paramount.

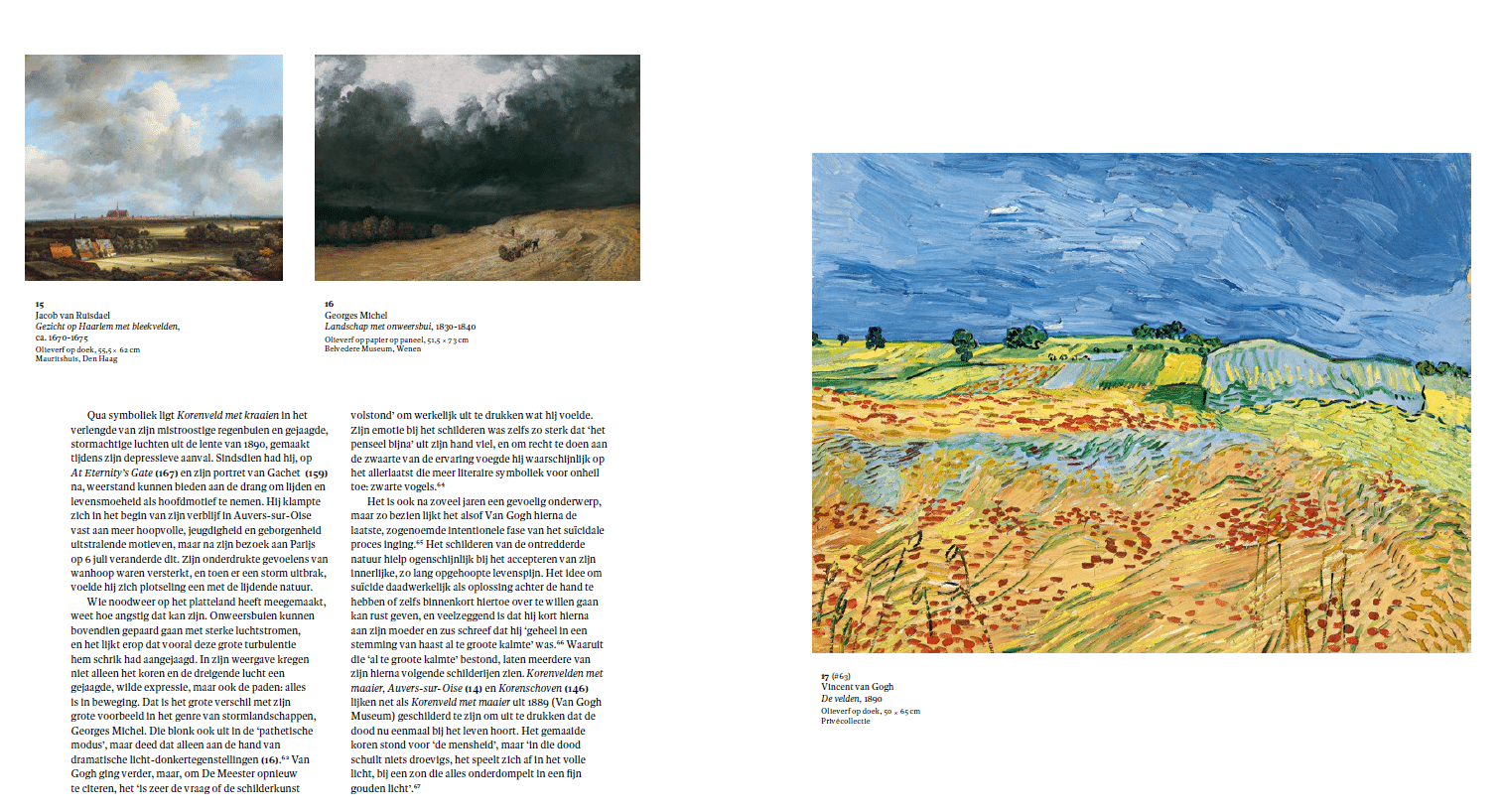

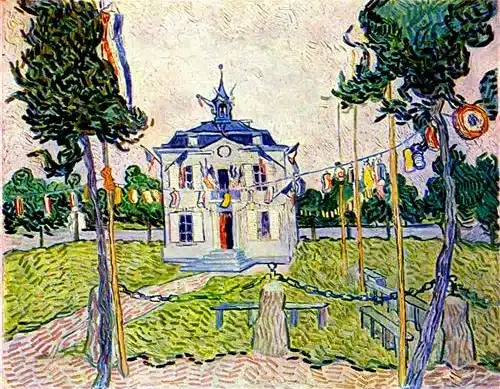

The reader can look at a triptych in which the portrait of Marguerite Gachet is positioned next to a chalk practice version and a letter to Theo with a plan and sketch of the painting – practising twice before going for real. The reader can look at the town hall of Auvers-sur-Oise, both as a drawing and as a painting. They can see how the dancing paint strokes encompass Van Gogh’s last Bastille Day, as the festive tricolour flags flutter on a square without people. On a double-page spread, the reader can look at blossoming chestnut trees that seem to greet each other in the middle of the street, against the backdrop of a menacing summer thunderstorm. The reader can look at a suite of flower still life that could fill an entire museum, as well as look at the wheat fields that connect Van Gogh’s landscape painting with the tradition of the seventeenth-century painter Jacob van Ruisdael.

A page from ‘Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise’ showing cornfields connecting Van Gogh's landscape painting with the tradition of seventeenth-century painter Jacob van Ruisdael.

A page from ‘Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise’ showing cornfields connecting Van Gogh's landscape painting with the tradition of seventeenth-century painter Jacob van Ruisdael.© Tijdsbeeld / Musée d’Orsay / Van Gogh Museum

Due to Van Gogh’s suicide in July 1890, the drawings and paintings he made in Auvers-sur-Oise became his last works. For great artists, the end of an oeuvre always appeals to the imagination – a kind of last dance with the canvas or paper. As a result, this is the interpretation of Van Gogh’s work in the final two months of his life that art history has predominantly taken. Still a young man, this period came rather early in Van Gogh’s life, but Auvers-sur-Oise is known as Van Gogh’s late style – the point at which all experience came together in a final creative outburst, to the climax of his ability, and which took on a special charge in the light of the revolver shot that followed. Was the festively decorated but empty square on Le Quatorze Juillet a sign of his own inner sorrows? Were the deep blue, almost black skies that loomed behind the flowering chestnut tree a symbol of the disaster in his own life, which in reality was only just beginning to come into blossom?

For Van Gogh, the intensity and depth of his last works are reflected in his biography – the relationship between psychiatry and art in the final part of his life, and the time he spent in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise in the north of France. This area of countryside was accessible by train from Paris, which is partly why it became so loved by artists. Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir and Camille Pissarro also stayed there for a while.

Auvers-sur-Oise Town Hall on 14 July 1890, 1890

Auvers-sur-Oise Town Hall on 14 July 1890, 1890Private collection

Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise presents the results of new research more so than Lloyd’s The Drawings. The catalogue meticulously records the places in and around Auvers-sur-Oise that Van Gogh visited and describes his encounters there in detail. The book includes maps showing the locations in and around the village where he produced work. Van Gogh painted the church and the town hall, the farms and houses in the hamlet of Cordeville, the gardens of Château de Léry, doctor Paul Gachet, his house and family members, and the fields, vineyards and landscapes on the banks of the river Oise.

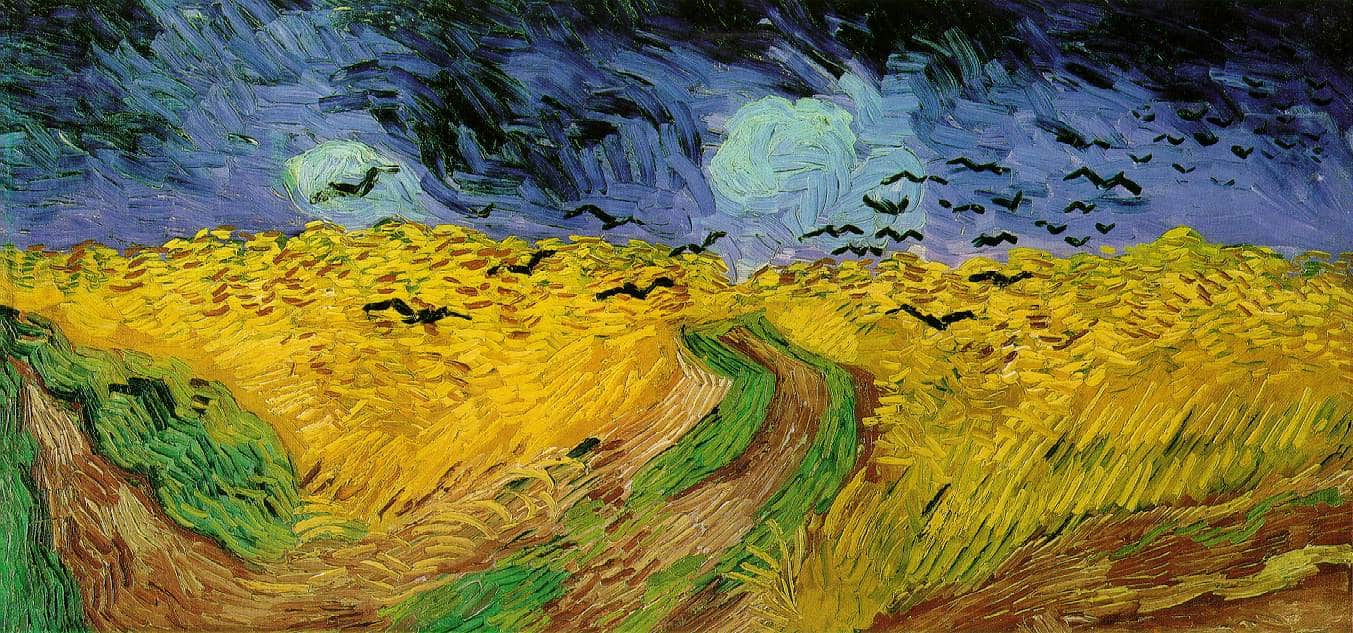

Vincent van Gogh painted Wheat Field with Crows in the last months of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise. ‘I have emphatically tried to express sadness and extreme loneliness in them’, he wrote to his brother.

Vincent van Gogh painted Wheat Field with Crows in the last months of his life in Auvers-sur-Oise. ‘I have emphatically tried to express sadness and extreme loneliness in them’, he wrote to his brother. © Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Wheatfield with Crows, completed in a summer storm, and one of Van Gogh’s most famous works, was painted slightly outside the centre of the town, in the fields surrounding the cemetery. He wrote to Theo after completion on July 10th, 1890, “They are immense, vast wheat fields under wild skies and I have emphatically tried to express sadness and extreme loneliness in them.” Van Gogh created his last work, Tree Roots, on July 27th near the Café de la Mairie, where he rented an attic room. An old postcard which surfaced in 2020 has helped to find the last place he painted. Two days later he died in his room, about a hundred meters away.

“My plan is not to spare myself,” he had already written in 1883, “not to avoid emotions or difficulties. It’s a matter of relative indifference to me whether I live a long or a short time.”

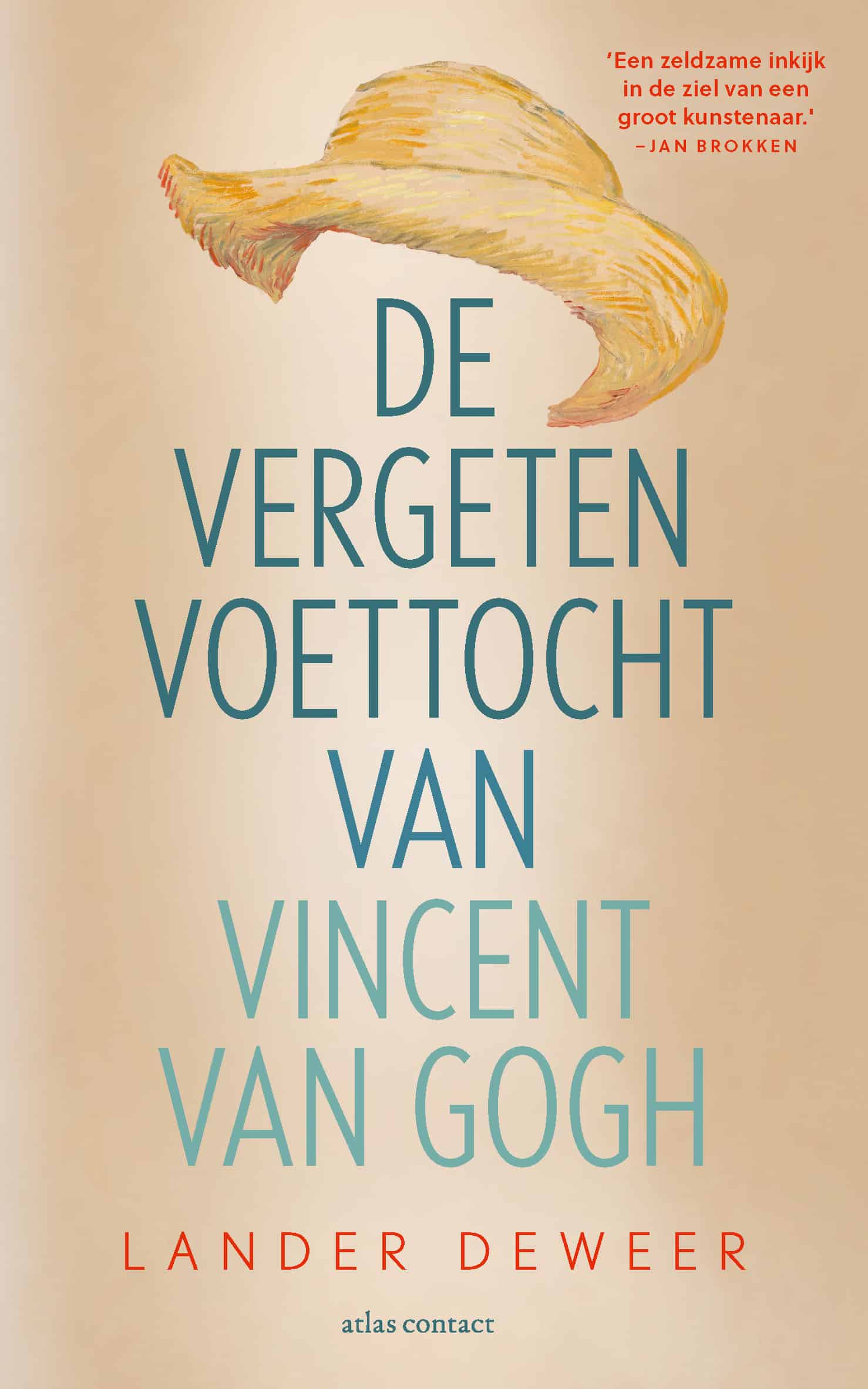

A book of a completely different ilk is De vergeten voettocht van Vincent van Gogh (The forgotten walk of Vincent van Gogh) by Lander Deweer. Rather than an art historical study or catalogue, it is a journalistic reportage. The book is set in 1879, shortly before Van Gogh converted to art, and tells the story of the journey Van Gogh undertook after being dismissed as a preacher. He moved from the Borinage to the municipality of Sint-Maria-Horebeke in the Flemish Ardennes, where he met the painter and preacher Abraham van der Waeyen Pieterszen. Did this man play a role in Van Gogh’s budding artistry? Deweer’s book revolves around this question, and fans out from Van Gogh to the demise of the Geuzenhoek – the most Protestant church community in Sint-Maria-Horebeke – showing how this globally renowned painter can also be seen as an almost mythical part of the traditions of a small village community. Pieterszen’s great-great-grandson, who still lives in the municipality, continues to tell the stories.

Deweer’s book is primarily literature, reportage, and sometimes almost folklore. In his search for the origins of Van Gogh’s artistry, Deweer is guided by Pieterszen’s descendants and by the visual artist Johan Tahon, who says convincingly, but still with a question mark: “Without Pieterszen, Van Gogh might never have become an artist?”

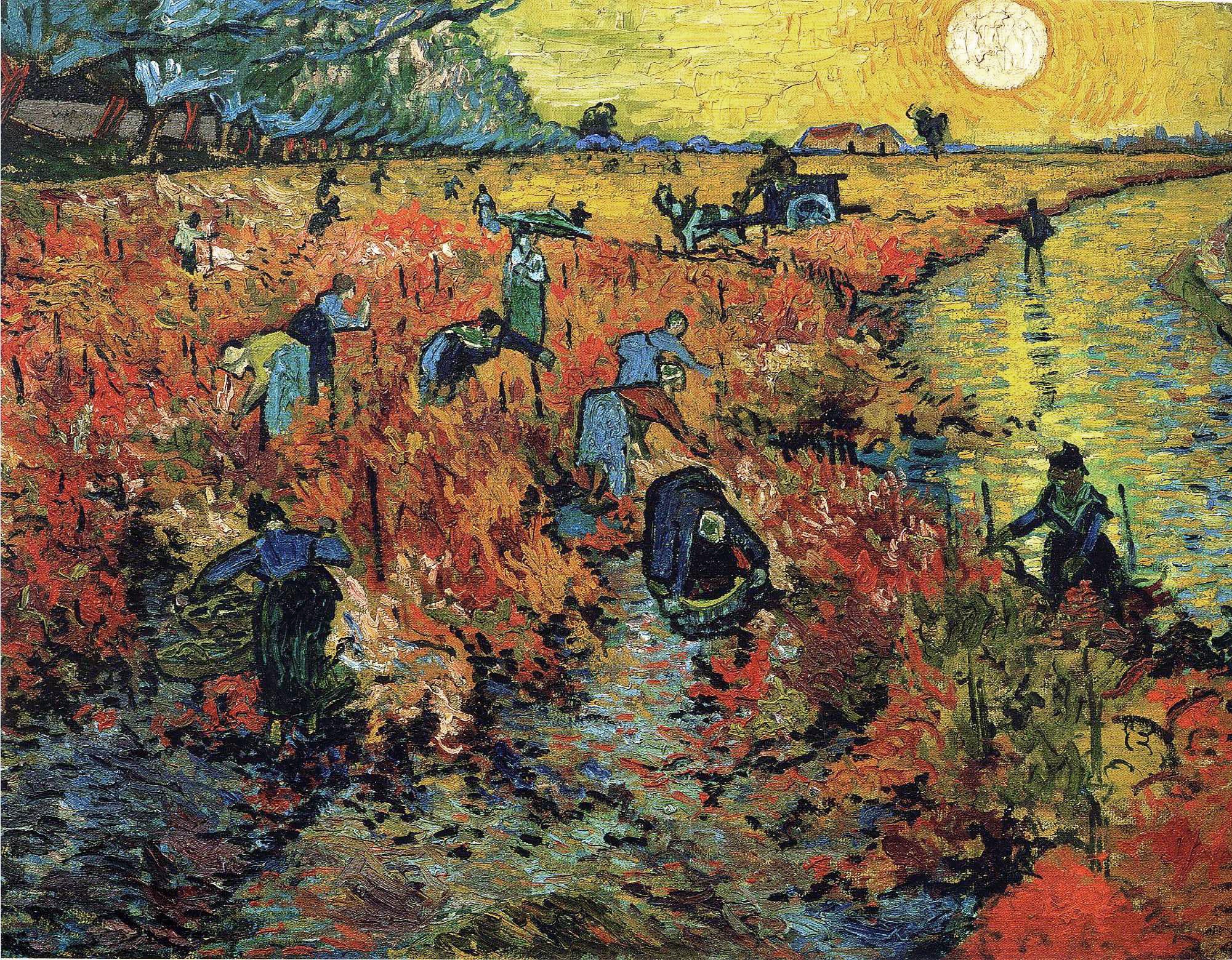

The Red Vineyards near Arles, 1888

The Red Vineyards near Arles, 1888© Pushkin Museum, Moscow

However, in terms of art history, the book is on the margins. Van Gogh in Belgium is more of a metropolitan story, visiting the academies of Brussels and Antwerp and the avant-garde society Les XX, who exhibited at and appreciated Van Gogh even during his lifetime. Members of Les XX later visited Van Gogh’s sister-in-law Jo Bonger in Bussum, and in 1893 a small edition of his letters was published in the literary magazine Van Nu & Straks. They are accompanied by a drawing of cypresses that Lloyd also discusses, and about which Vincent wrote to Theo in June 1889, “The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it surprises me that no one has yet done them as I see them.”

Van Gogh sold a work through Les XX to Anna Boch, herself a painter and daughter of the wealthy family of the famous porcelain. The Red Vineyard (1888), dating from the period when he painted in Arles, shares nothing of the ominous work from Auvers-sur-Oise. Bent under the glowing evening sun, and set in bright colours, the workers pick the harvest.

- Christopher Lloyd, The Drawings of Vincent Van Gogh, Thames & Hudson, New York, 2023, 224 p.

- Nienke Bakker, Emmanuel Coquery, Teio Meedendorp and Louis van Tilborgh (eds.) Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: His Final Months, Tijdsbeeld/Van Gogh Museum, Gent/Amsterdam, 2023, 255 p.

- Lander Deweer, De vergeten voettocht van Vincent van Gogh, Atlas Contact, Amsterdam, 2023, 200 p.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.