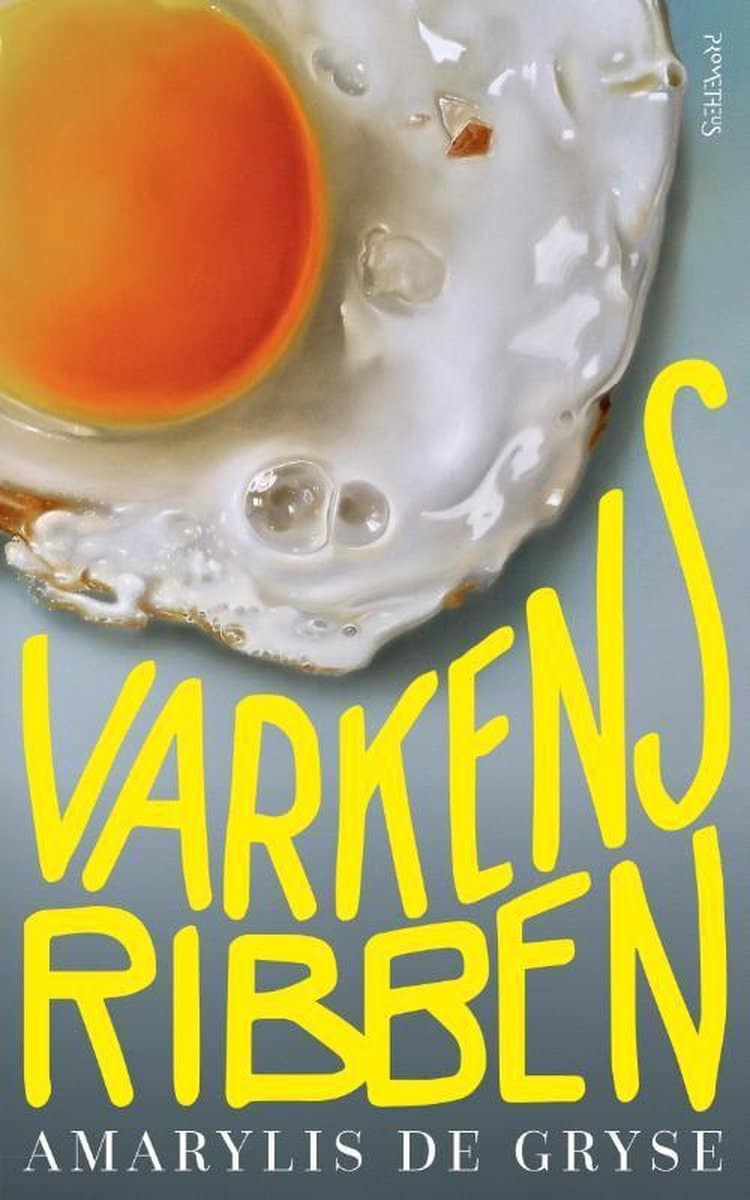

‘Varkensribben’ by Amarylis De Gryse: Stuck in the Revolving Doors of Life

In Varkensribben (Pork Ribs) by Amarylis De Gryse, people eat a lot, and people turn around in circles. This is a melancholic and funny debut novel about people who tend to follow the herd but still want to be noticed. Have to be noticed.

There has been much speculation about the first ‘corona novel’ and how closely it should mirror current events, but perhaps it pre-empted the crisis.

Perhaps it was written just before the outbreak of the pandemic, for example, by Amarylis De Gryse (b. 1989), who grew up in a non-descript village on the outskirts of Bruges and now, she says, writes her stories and books in a cabin in the woods along a motorway in the Kempen region, where she is also retraining as an organic farmer.

Amarylis De Gryse

Amarylis De Gryse© Marianne Hommersom

Precisely because the words corona and COVID-19 are completely absent, this book harks back so strongly to the oppressive atmosphere of last spring. Marieke, the main character, works in a care centre, where looking after the elderly residents who are increasingly sick steadily falls to fewer and fewer staff.

The circumstances, a heatwave, and an imminent move to a new building work against them, while Marieke is also going through a personal crisis. She has been kicked out by her boyfriend, a butcher’s son, and sleeps in a rental car that she parks along the canal every evening. And her summer clothes are stuck inside a washing machine at the laundrette, so she has to wear clothes that are unseasonably warm.

No, life is really not going well for Marieke this summer.

Precisely because the words corona and COVID-19 are completely absent, this book harks back so strongly to the oppressive atmosphere of last spring

Driven by a cynical, business logic, the director of the nursing home decides that the elderly people with dementia on Marieke’s floor, precisely those residents who are suffering most, should stay in the old building for a bit longer, while the rest move to a shiny newbuild over the road.

That looks better for the politicians and other dignitaries attending the opening, who should not have to be faced with drooling, incomprehensibly babbling old people.

But the situation remains dire long after the opening. In the old premises, Marieke is the only carer left, electricity and water are cut off, and sausage with apple sauce is the only thing on the menu. One by one the residents die, exactly as management intended.

Against all this we get to know Marieke, a child of divorced parents who has a fragile bond with her mother, and hardly knew her father. Her memories of childhood, of what she experienced and with whom, are distorted. This makes her think about who she is exactly.

Seemingly without effort, De Gryse weaves her storylines, until they all come together in a great finale

Marieke knows that she has always been more of a follower. But that does not mean she has no sense of her own value. Followers want to be seen, too, appreciated for their contribution to life, they want to step out of line every now and then, rebel against chilling hospital directors, absent parents, sisters who keep secrets for too long.

Of course, that does not always go smoothly, that’s how it is in the lives of followers. Marieke keeps turning in circles, sometimes literally. Whether on the roundabout near her hideout on the canal or in the revolving doors of the new residential care centre.

As she spins in circles, she fantasises about how life could have been. Better. More adventurous. Fairer. For her, for her relationship, for the elderly residents on her floor. Eventually, she releases the rebellious Marieke in her, in the hope that everything will be alright.

Amarylis De Gryse, who has published short stories and was selected for deBuren’s writing residency in Paris, tells Marieke’s story in a melancholy, funny way, full of subtle hints and gorgeous metaphors.

Her opening line immediately sets the tone: ‘That’s life for you: you are thrown out of your house just when you should be putting a wash on.’ That kind of bad luck and the fated convergence of disappointing circumstances appears to be a common thread in Marieke’s life, but she knows how to deal with it with humour.

Seemingly without effort, De Gryse weaves her storylines, until they all come together in a great finale. Food plays an important role here. In a Proustian way, pralines, sausage with apple sauce, meatballs, onions sizzling in butter, bacon and eggs, and of course pork ribs evoke all kinds of sensory memories that draw you into Marieke’s inner world.

You could almost write (forgive the pun): a debut that leaves you with a taste for more.

Excerpt from ‘Varkensribben’, as translated by Paul Vincent

pp. 5-7

Such is life: you’re thrown out of the house just when you were about to do the washing. Never when everything is folded up fresh and neat in the wardrobe. I’m naked and a man drums harder and harder on the windscreen of my car, shouting louder and louder: ‘Girl, girl, girl!’ and I have no idea what time it is. I know it’s the weekend, and that it’s morning because the sun is forcing its way in. Not just through the little chinks here and there, no, but also right through those thick bath towels that I hung up in my car yesterday.

‘Girl, girl,’ again and again, and that banging, so I push myself upright, throwing off my blanket, survey the mess at my feet and grope for my watch among it. All that my fingers encounter is yesterday. The half bag of crisps, the empty packet of chocolate biscuits, my telephone on which I watched naked bodies far into the night. Bodies that leapt violently on each other, that circled each other and restlessly stuck their tongues in each other, who tried to grasp* each other with sucking and licking until my battery ran out. And I: on my back, under this small fleece blanket, two pillows pressing on the bare skin between my thighs. Pressing with all my might until it felt like that: like the weight of someone else, a present body, like that warmth. I felt nothing. Then I grabbed for the biscuits.

The cold glass of my watch kisses my little finger. Not quite six o’clock, I see. Meanwhile the banging is more and more hurried and now the man who belongs with the voice is trying to open my car, but I locked everything, yesterday. I thought I had parked out of sight. I had even been for a short walk along the towpath, just like the previous days, from left to right and back the other way in order to be sure I was well hidden among the bushes along the canal. I rummage around for my trousers, twist in an unnatural arc to get them over my hips and then quickly pull my sweater over my bare torso.

‘Girl!’ cries the man’s voice. A flat hand seems to be falling on the roof of my car in defeat. My voice is hoarse when I answer that I’m coming. I unlock the car, push the door open and see that it’s the fisherman standing by my car. His eyes are bulging, I am careful getting out. Just imagine my sliding forward belly first on an avalanche of my rubbish at his feet. Only the biscuit packet falls out. I don’t know why the fisherman shouts out, now, it’s like a mixture of relief and rage: ‘Look at you, girl!’ And then: ‘There’s someone in the water.’

‘Do you mean dead?’

‘Yes.’

He doesn’t wait for a reaction, turns and runs back to the canal. I follow him in bare feet, along the towpath, onto the dewy grass and there, not far from the bank, lies a woman, face down in the water. ‘It took me four casts to catch her,’ says the fisherman. I imagine how he would have reeled her in.

We watch together as the police arrive, and when a policeman looks first at my bare feet and then asks who the car in the bushes belongs to, the fisherman says that it’s ours and that the towels are to keep off the rising sun.

‘Are you sleeping here?’ asks the policeman. ‘Because it’s not allowed.’

‘Of course not,’ says the fisherman. He takes his roll-up tobacco out of one of the many side pockets in his beige trousers and skilfully rolls a thin cigarette. His hands are weathered. He exhales smoke and watches the policeman walk away.

‘Thanks,’ I say.

‘Isn’t it time you were going home,’ says the fisherman, and I say I have to go to work.

‘I thought it was you,’ he says. There are crow’s feet around his eyes.

‘Her blouse, you see.’

I nod and say nothing, since I can hardly say that I thought the same.

Amarylis De Gryse, Varkensribben, Prometheus, Amsterdam, 2020, 222 pp.