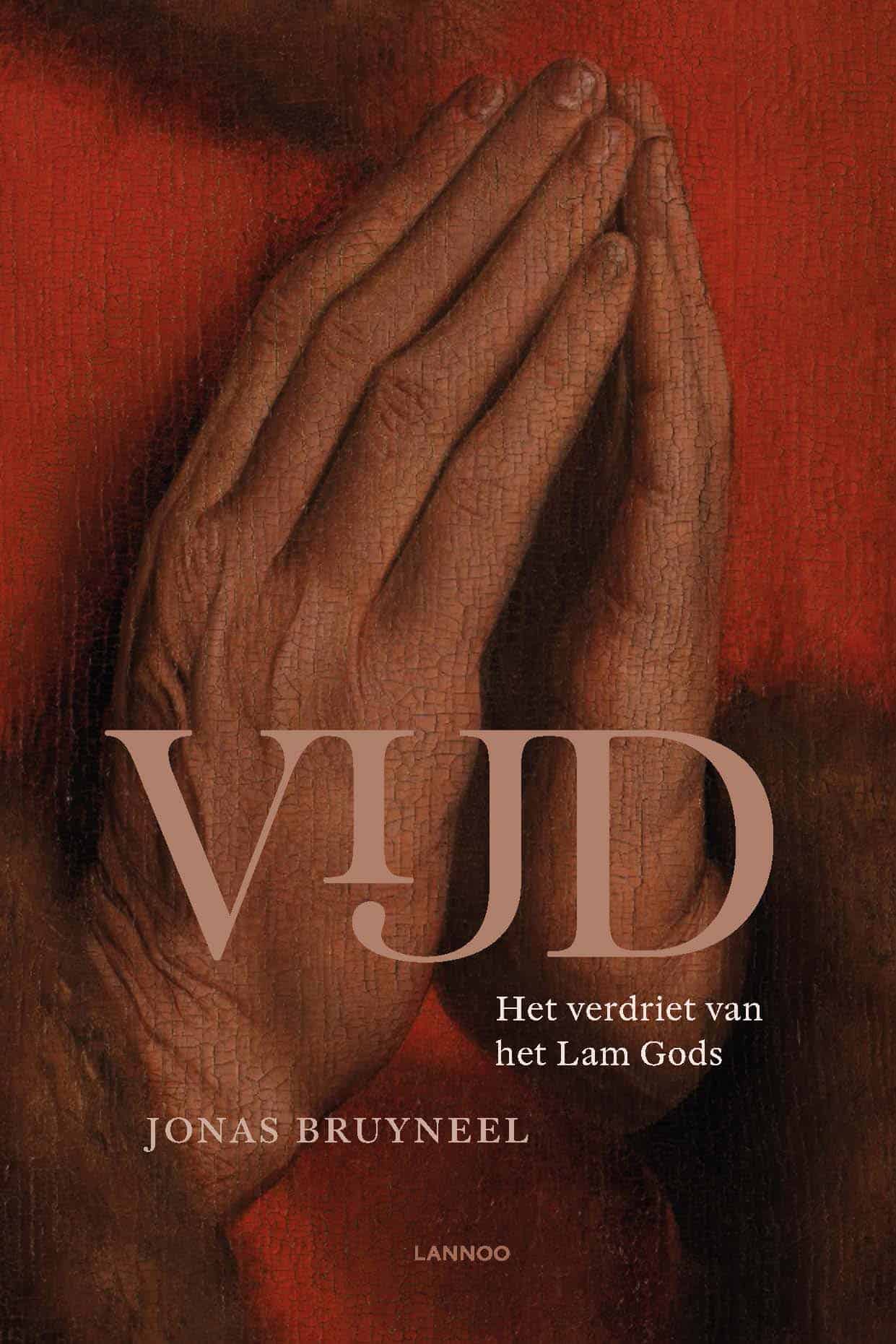

‘Vijd’ by Jonas Bruyneel: A Vibrant Portrait of a Burgundian Family

Every month we draw attention to a literary debut which garnered less notice upon release than it deserves. In his first novel Vijd: het verdriet van het Lam Gods (Vijd: The Sorrow of the Mystic Lamb) the young Flemish author Jonas Bruyneel paints a vibrant portrait of a Burgundian family.

In his book about the famous medieval altarpiece The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (also known as the Ghent Altarpiece) – by the Early Netherlandish painters Hubert and Jan van Eyck, which hangs in the St Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Jonas Bruyneel

sketches the rise and fall, in Burgundian Flanders, of the colourful family responsible for its commission. He does so with an eye for precision and historical detail, in a sensory language that transports us to the late Middle Ages.

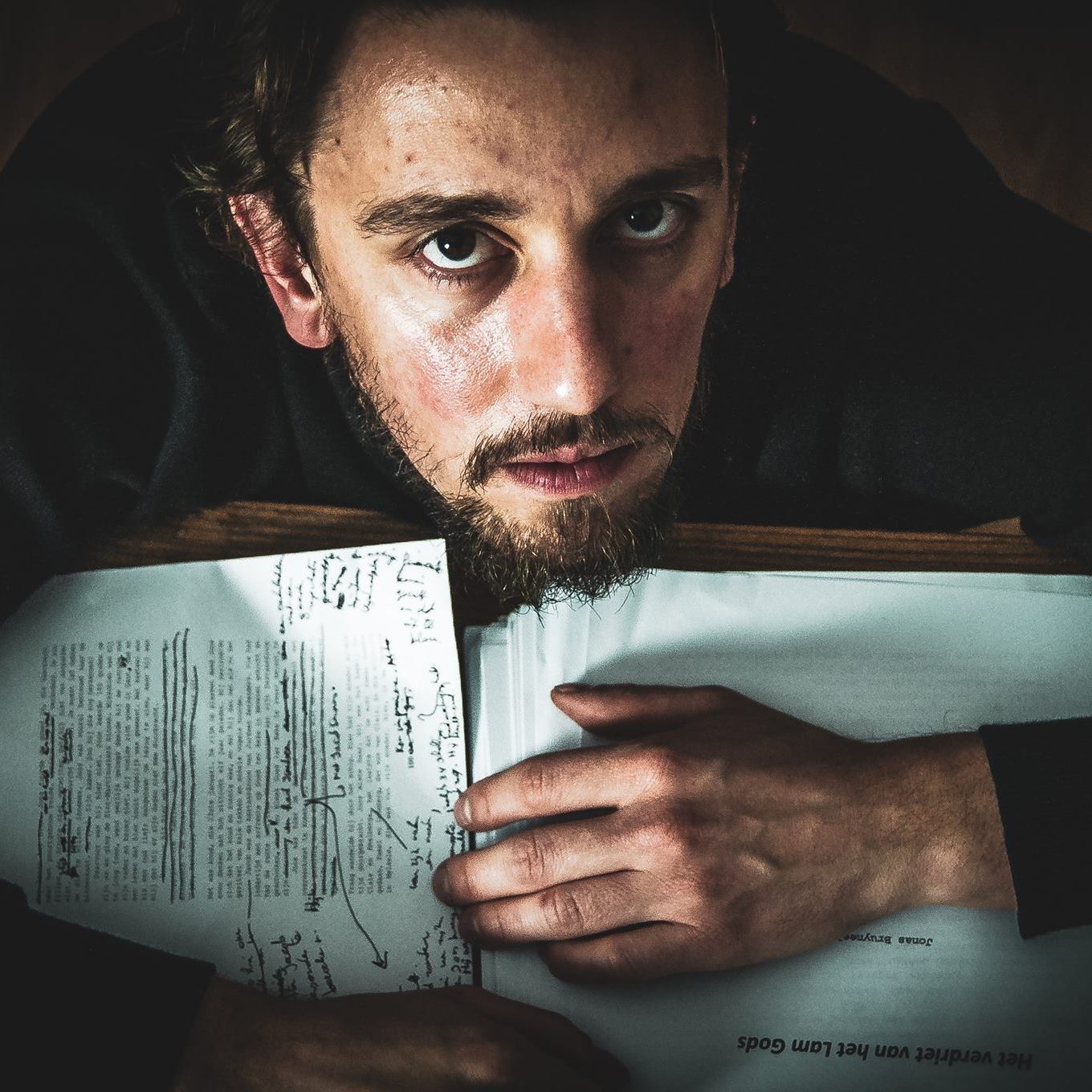

Jonas Bruyneel

Jonas BruyneelJudging by the sales success of a recently published book De Bourgondiërs (The Burgundians; De Bezige Bij, 2019), by Bart Van Loo, readers in both Flanders and the Netherlands have become extremely interested in the Burgundian principalities and origins of the Low Countries. Van Loo had already proved his writing talent with a trilogy on French culture and another fast-selling book, on Napoleon. It also helps that Van Loo is an ambassador for his own work, with his many appearances on television that show him to be funny and intelligent. Still, the sensation he achieved with his The Burgundians was simply astonishing.

Other authors of historical works and novels, however, usually attract rather less interest, which is unfortunate, as we can see in Bruyneel’s book, which similarly appeared this year and is set in the same period as Van Loo’s bestseller, though Bruyneel could hardly be suspected of trying to ride on its wave of success.

Indeed, Bruyneel laboured on this story for years, locking himself away in archives and castles, studying family trees, maps and invoices. He also got stuck in the mud of fresh swamps in Beveren, learnt how to ride a horse, cut blocks of peat, paint with oils and tan leather. And he spent hours both in the St Bavo’s Cathedral and the Museum of Fine Arts (MSK) in Ghent, where the outer panels of the ‘Adoration of the Mystic Lamb’ by the Van Eyck brothers were restored from 2012-2016, for the largescale Van Eyck exhibition in 2020.

All this research could have made for a rather dry book in less skilled hands. Not so with Jonas Bruyneel, who debuted in 2015 with the short story bundle Voorbij het licht (Beyond the light; aquaZZ, 2015) and from 2017 to early 2019 was the ‘setter of letters’ of Kortrijk, the contemporary spin given in south-west Flanders to the role of city poet.

Bruyneel brings to life the characters and motivations of the Vijd family. Joos Vijd in particular features extensively: the last, childless heir of the Vijd estate is terrified of being forgotten and of dying an insignificant death, a fear that he appears to share with painter Jan van Eyck. Vijd commissions a painting from Hubert van Eyck, after whose death in 1426 Vijd successfully lobbied the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, to have the work finished by Hubert’s younger brother Jan. This is the work that was to become the world-famous ‘Adoration of the Mystic Lamb’, and save Joos Vijd from oblivion, immortalised as he is, along with his wife, on its outside panels.

Bruyneel begins his story in 1430, with a contemplation of an elderly Joos Vijd in the building work that became his chapel in the St. John’s Church, later the St Bavo Cathedral. In a sensory depiction, Bruyneel evokes the smell of wet wool hanging there, how the dust particles swirl in the light. This sets the tone for a story that really starts in 1325, with the Vijds living in Waasland, unfolding chronologically from then on.

The correct historical facts are fleshed out by people with real emotions and their motivations, trustworthy or otherwise, and embellished with sensual descriptions of landscapes, cities, churches and painters’ workshops. We smell the paint and see shadows fall. We are party to the doubts and fears of the silent, rational and pious Joos Vijd, present at the festivities of his marriage of convenience to Elisabeth Borluut, of Ghent, and witness to the fraud, preaching and diplomacy (not necessarily in that order) needed to acquire power in the County of Flanders.

Vijd, as a result, is a very vivid book, a timeless historical novel about ambitions and weaknesses, dreams and disillusions, joy and sorrow, the rise and fall of a family craving recognition.

Two excerpts from Vijd, as translated by Paul Vincent

First excerpt – start of the story, pp.17-18

1430 – JUST THE MEMORY

Joos remembered the smell of sheep. He stood in the middle of the still bare space, right under the cross vault, and all he could think about was the odour of wet wool. Of the strayed flock that after a storm had trooped together on one of the few spared pieces of land. And he who had stood watching with his father. His father was a man who in every situation knew what he must do. He had peered across the flooded plain, sniffed and said to him: ‘Joos, this is the smell of loss.’ Now, alone in the middle of this nearly finished construction that was to be his chapel, he could smell nothing but that smell. The smell of wet sheep. The smell of loss. His eyes followed the ribs of the vaulting. In the ridge he tried to make out the coats-of-arms of his family, the Vijds and that of Elisabeth, the Borluuts. His eyes were not as good as they used to be.

Joos heard footsteps. Shortly he would himself go out through the nave, out of the Sint-Janskerk into the hubbub of the town. He would walk via the belfry to the harbour. Another spot that reminded him of his father. Where his father had shown him the ropes, in that busy assortment of corn chandlers, merchants and skippers.

It was quiet here. Here he could be alone. Elisabeth found peace among the pear trees, apple trees, plums and elders in their garden. He needed this vault. The light came in through the stained-glass window and cast a richness of colours and nuances on the floor. He stood in the middle, saw how by his feet his shadow broke the streaming of the light. Joos wished he could leave that shadow behind here. Part of himself would prove for ever that he had been here. That he had existed.

That he had built this, this space, where beads of resin and candle smoke drove the smell of sheep from his memory. He had built this. With his work and will power. With his sorrow and futility. This was his, theirs, his and Elisabeth’s. Just as the chapel in the Sint-Martinuskerk in Beveren was his mother and father’s.

Second excerpt – Joos Vijd and his wife Elisabeth are visiting the studio where Hubert van Eyck is working on the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, pp. 208-209

He had Johannes van Impe and Joos to think of, but at the same time hid winks in the painting that could only come from him. He was working for his client, but had learned that he must not only copy the world, but must expose its soul.

His wife kept at a distance, he noticed. She had better eyes than her husband. Hubert saw that Elisabeth was studying the garden. Silver firs. Trees that never faded and never lost their needles. That she was examining the spring flowerers and probably recognised medicinal herbs which she also found in her own garden. Joos looked for details, but Elisabeth seemed to understand better than him that this was a whole in which no character, plant or animal said anything without what surrounded them.

Hubert was an observer, He had learnt how to read and dissect the world. They didn’t understand the half of it, the old couple who were dominating his life at present. He himself was not frightened of death. He knew that his work would keep him alive. But if the urge to go on living was proportionate to the fear of dying, those two must be constantly in fear of death.

Elisabeth seemed to him to be a sensible woman. The questions she asked confirmed that. Hubert pointed out to her the leaves of the wild strawberries and white clover. His visitor followed his extended hand, past her husband.

‘Always in threes,’ he explained. ‘To show that that perfection need not be grandiose.’ That she could find it in smallness, he told her, in the things she saw every day but never looked at properly. And that those plants in that way came closer to the divine than she as a human being could ever do.

Elisabeth nodded. He knew the grief in their life, that their family would disappear with the man who now took a step back and breathed heavily. He wanted to express that in the altarpiece too: that at the bottom of all that magnificence lay helplessness.

She felt it. He could see that from the way her shoulders slumped a little and her hands slid languidly along her body. From the way she seemed to count each leaf. He wanted to point out to her the seven leaves of the lilies-of-the valley, which let their heads droop, as if to show her that everything she meant here was ultimately of little importance.

Jonas Bruyneel, Vijd – Het verdriet van het Lam Gods, Lannoo, Tielt, 2019, 256 pp.