Village Idiot and Troubled Genius, the Many Faces of Vincent Van Gogh in Cinema

At Eternity’s Gate, the most recent biopic about Vincent van Gogh, confirms the myth of the troubled artist who continues to fascinate both filmmakers and audience. However, in other films, the painter is portrayed as a village idiot or an artistic hero. Will the real Van Gogh please stand up?

It’s almost a first-person shooter in which the viewer is the one that picks up the brush and starts painting, yet for now, Julian Schnabel’s movie At Eternity’s Gate from 2018 offers the best alternative. A movie that lets you experience what it must have been like to wander through the fields in the shoes of Vincent van Gogh. Schnabel uses many point-of-view shots, which allow you to see the world from the perspective of the protagonist. Schnabel depicts Van Gogh’s gaze as varifocal glasses – half-sharp, half-blurred – and also coloured by a heavily applied yellow or blue filter. Van Gogh – the experience.

Whodunit

It has already been possible to walk through Van Gogh’s world of paintings in the fully animated Loving Vincent (2017). In a dream sequence, the viewer could look through Vincent’ eyes, this time looking at his bleeding belly wound: wondering whether he had really done it to himself. The movie took 130 of Van Gogh’s paintings as the basis for a whodunit that questions the circumstances surrounding his suicide. Schnabel goes further by making a clear choice for the murder variant that was launched in 2011, and which has been fiercely contradicted by the Van Gogh Museum – as guardian of the art-historical heritage.

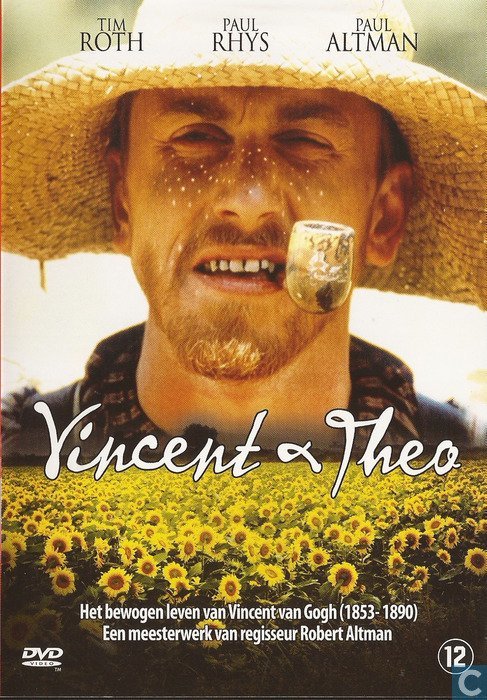

The facts are not central to this article, as storytellers are free to (re)interpret them by their own truth. Or as filmmaker Robert Altman, who produced Vincent & Theo (1990), put it: by definition, artists represent a different truth than the known, accepted norm. This piece therefore focuses on the question of how Vincent van Gogh has been portrayed in movies over the years and what that says about the world that feeds those stories. After all, what is it that appeals to us so much in the myth of the troubled genius? And why do we all aspire so eagerly to stand in his shoes?

Posthumous success

In general, Van Gogh was not even recognized as an artist. The tragedy of the rejected man, ignored and ridiculed by society, offers comfort to every soul that is in need of self-confirmation. Most people struggle to hold their own in a society that they did not shape themselves. In this light, Van Gogh’s suicide can be interpreted as the ultimate act of autonomy, of anarchy. In addition, his posthumous success offers hope that one day, it will be different. That the last ones will be the first ones, even if it is only after death.

Do we still see the man and his work through the myth or have they become travesties that tell more about ourselves?

Behind his legacy lies a stark irony – despite cultivating his image as a rebel, and non-conformist figure, he has since been posthumously embraced by society and recognized as an exemplary artist. A dead artist is a relatively harmless one, since everyone can interpret and mythify his legacy to their heart’s content. However, do we still see the man and his work through the myth? Or have they become travesties that tell more about ourselves and our needs than about the source?

Troubled artist

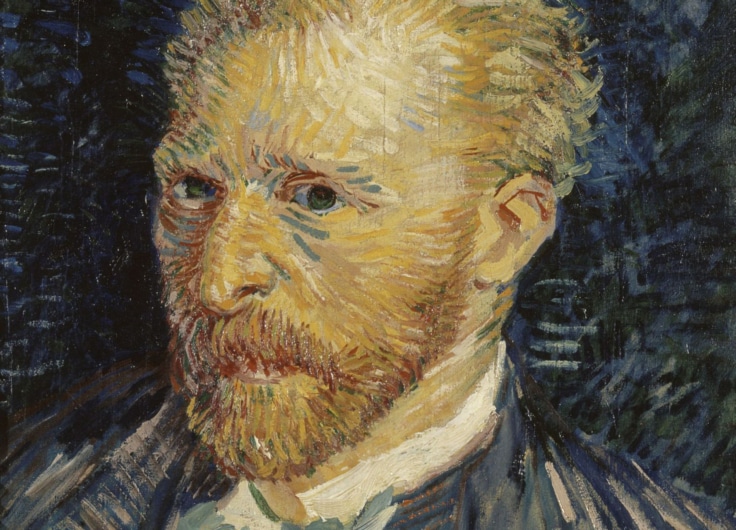

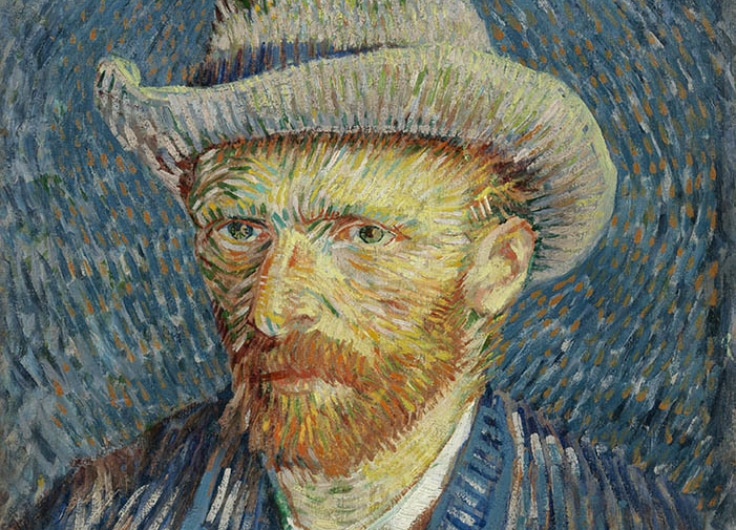

Shortly after Van Gogh’s centenary, the first movie about Van Gogh appeared, which elaborates on the creation of his most famous works. Lust for Life (1956), directed by Vincente Minnelli, was based on the 1934 bestseller with the same name by Irving Stone. As in more popular biographical novels of that time, the troubled artist is central. A legacy from Romanticism, in which tragic heroes, following the footsteps of Goethe’s young Werther, would rather die honourably for a personal ideal than give in to a bourgeois morality imposed by society that was not theirs.

In later decades, the individualistic ideal was adopted mainly by artists who, by definition, question and reinvent reality, challenge current rules and ignore them. Consequently, an artist that is somewhat ahead of his or her time is by definition a misunderstood rebel.

Still from Lust for Life (1956), starring Kirk Douglas as Vincent van Gogh

Still from Lust for Life (1956), starring Kirk Douglas as Vincent van GoghTragic hero

In Minelli’s Lust for Life – a successful Hollywood melodrama starring Kirk Douglas as main actor and Athony Quinn in an Oscar-winning supporting role as Gauguin – Van Gogh is portrayed as a driven idealist who develops into a tragic hero: A man of the people who identifies with the poor miners of the Borinage. Just like them, he lives in a shabby house and sleeps in a straw bed – something that his fellow preachers from the wealthy bourgeoisie disgracefully speak of. Drama after drama follows with child labour and mining accidents, while Vincent holds out a helping hand. The dramatic orchestration on the soundtrack is as epic and heroic as in Ben Hur, which will appear three years later. Impotence, frustration, and self-doubt are the three forces that drive Van Gogh.

Modern messiah

His psychological crises are depicted theatrically and with a sense of hysteria. As the story progresses, the distance between the ‘ordinary’ world and Van Gogh’s interpretation of it grows, illustrated by a realistic shot of a lamp next to Van Gogh’s pronounced impression of it on canvas. We see him cutting off his ear in front of a mirror, tormented. An act that definitively reduced him to a village idiot.

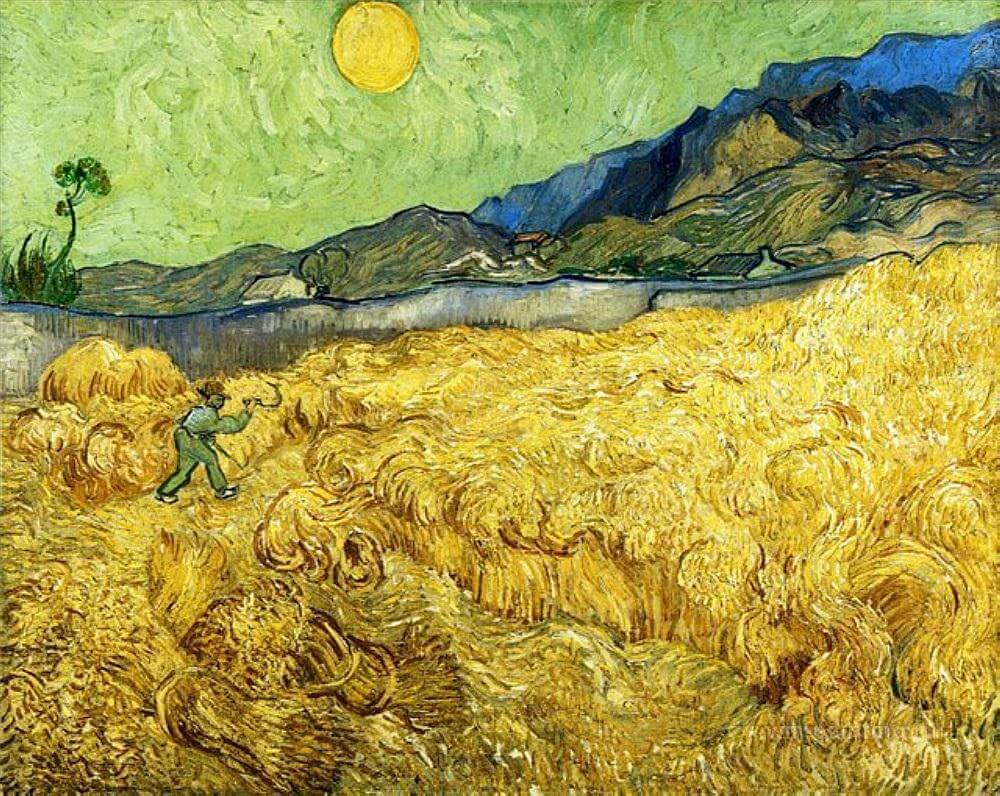

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with a Reaper, 1889

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with a Reaper, 1889© Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Stichting)

His suicide, however, is not interpreted as an idealistic choice or tragic defeat, but as a response to a long-felt desire, a homecoming in a sun-drenched Elysées cornfield, as he painted it in ‘Wheat Field with a Reaper’. A man who loved life, but couldn’t handle it. A hard worker, who was rewarded by God. Lust for Life is a passionate play about a secular Christ, a modern messiah. This was undoubtedly a controversial statement in the 1950’s, because killing oneself was not exactly accepted among believers.

The long list of museums that are thanked at the beginning of the movie for making their Van Gogh works available for photography is striking. The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam did not exist yet. However, the fame of Van Gogh’s work in the 1950s and 1960s grew partly as a result of the collection travelling around the world, which was given a home in 1973 when the Van Gogh Museum opened its doors in Amsterdam.

Van Gogh industry

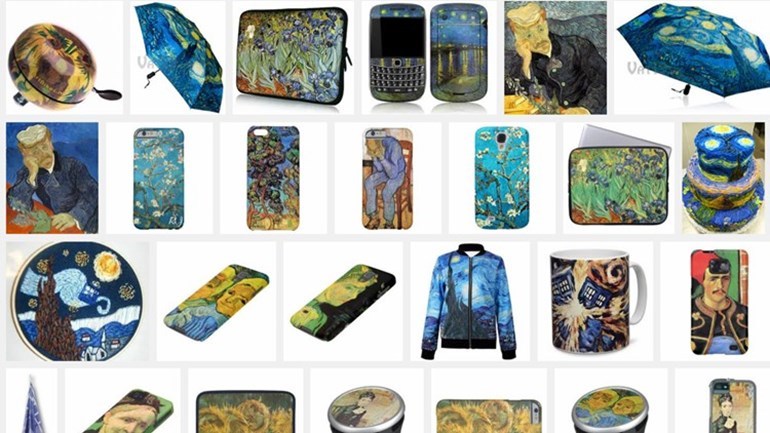

The situation is very different three decades later, around Van Gogh’s hundredth anniversary of his death in 1990; his work is now among the highest-paid in the world. Newly released movies about him were remarkably critical of Van Gogh’s popularity. In a collection of essays published around that time, entitled ‘The Mythology of Vincent van Gogh’ (Japan, 1992), there was a chapter devoted to ‘the Van Gogh industry’, which had grown enormously.

Van Gogh merchandise

Van Gogh merchandise© Vans

For example, a Dutch entrepreneur who registered Vincent van Gogh as a trademark in sixty countries, became a multimillionaire because he receives royalties for every t-shirt, perfume, or tie that is brought to market under his name. The author of the article, however, is pleased to note that the Van Gogh Museum, confronted with unbridled kitsch caused by commercialization, is ‘bravely holding its ground’ by restricting itself ‘in the name of the art’ to the mere sale of books, catalogues, postcards, and posters.

Anarchist

In 1990, the American director Robert Altman published Vincent & Theo, a movie concerning the connection between the uncompromising artist and the brother who, as an art dealer, unsuccessfully tries to sell his work to an uninterested audience. The movie is about misunderstood art and denounces the hypocrisy of the general public that did not show any interest in the brothers when they were alive, but embraced them after their death.

film poster of Vincent & Theo (1990)

film poster of Vincent & Theo (1990)Altman opens with documentary images of the millions auction of Sunflowers at Sotheby’s in 1987 and finishes with Theo, naked in the basement of an insane asylum, who shouts in despair: ‘Vincent, where are you?’ while he directs his gaze straight to the camera. Altman’s Van Gogh (Tim Roth) has rotten teeth and becomes more and more smeared in paint – and eventually in blood. Altman portrays him as an anarchist and has Gauguin make a declaration of solidarity with the words: ‘All artists are crazy’.

No glorification

A year later, Van Gogh (1991) by the French filmmaker Maurice Pialat is released, starring Jacques Dutronc, who lost ten kilos for his role. Pialat, who was a painter before he became a filmmaker, also portrays Van Gogh in a contrary light in his movie, avoiding earlier associations of myth and glory. He shows an earthly Van Gogh, which he follows during his last 67 days.

Pialat’s Van Gogh has curved shoulders, looks worn down, ordinary and simple. The focus on his paintings is modest, dramatic events are ignored or shown almost casually. The ear of Pialat’s Van Gogh is at most scratched, but not cut off.

Here, Van Gogh is an outsider who, although he walks among humans, does not seek approval. He lives for his work and is not really known to anyone. The relationship between the brothers is much less harmonious than in Altman’s movie. Pialat finishes with a shot of Marguerite, the daughter of Van Gogh’s treating doctor Gachet, who is constantly following Van Gogh throughout the movie. But he doesn’t follow her. When she posthumously declares: ‘he was my friend’ – this statement raises some serious questions.

Van Gogh: a free man

Anyone who has something to say about Van Gogh is appropriating him. That’s why the Japanese director Akira Kurosawa emphasized that the narrator will always use what suits him for his interpretation of Van Gogh. The fifth, playful chapter in his collection of short fiction films Dreams (1990) is devoted to the Dutch master under the title Crows. It shows a young artist that is drifting away on Van Gogh’s work in a museum – and then finds himself in his paintings. The master himself – performed by American director Martin Scorsese wearing a straw hat and having a bandaged ear – is found on the inevitable wheat field.

Still from Crows (1990)

Still from Crows (1990)The sun-possessed master, however, has no time at all for the visitor; he wants to get on with his work. Thereupon, Kurosawa shows black and white images of the fast spinning wheels of a steam locomotive, accompanied by the sound of a steam whistle. When asked about his cut-off ear, Kurosawa lets van Gogh refer to a fictional explanation from a previous novel: ‘Yesterday I was working on a self-portrait. I couldn’t get the ear right, so I cut it off and threw it away!’

Kurosawa offers perhaps the most beautiful image: Van Gogh, as a human being, will not be caught by anyone

While the dreamer is trying to find Van Gogh in his paintings, the painter himself disappears from view behind the horizon of the ‘Wheat Field with Crows’. Once again the steam whistle blows, sounding like comical commentary. This breaks the spell and the Van Gogh admirer finds himself back at the museum again, where, out of respect for the master, he takes off his hat to the canvas.

In this way, Kurosawa offers perhaps the most beautiful image: Van Gogh, as a human being, will not be caught by anyone: we will have to make do with paintings on which we can project only our own fantasies. Kurosawa tries to find Van Gogh, but also sets him free.

Enlightened soul

After almost two decades, there is now a third film wave, as a response to Van Gogh’s suicide that has been questioned since 2011. Two movies have so far been produced: the fully animated Loving Vincent (2017), which was mentioned above, as well as Schnabel’s recently published At Eternity’s Gate (2018).

An intense Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate

An intense Willem Dafoe as Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity's Gate© TNS

While Loving Vincent questions the reliability of both the narrator and the witnesses that were consulted numerous times – including the outspoken gossipy ones and a quiet Marguerite – Schnabel focuses on the public’s identification with the painter. In a way, he returns to the mythification at the time of Lust for Life. He ‘corrects’ this history with the controversial murder theory and a sketchbook that appeared in 2016, of which its authenticity is equally controversial.

But Schnabel also elevates Van Gogh, the mad artist, back to a man who has eternal life – who, like an enlightened soul, lets go of the earth to become absorbed in his work. Unlike Minelli’s Lust for Life (1956), Schnabel’s style is subjective: with him, the viewer can experience for himself how a misunderstood genius becomes detached from time and place.

The pathetic and pretentious platitudes that Schnabel puts in Van Gogh’s mouth are rather compulsive

His romantic identification with van Gogh may also serve to put his (and our) own ‘rebellious genius’ in a better light. Schnabel – a successful painter himself – may have had a stubborn reputation, but he was never unappreciated: the Encyclopaedia Britannica calls him ‘an instant art world success when he was marketed by the young New York-based merchant Mary Boon’. The pathetic and pretentious platitudes that he puts in Van Gogh’s mouth are rather compulsive: ‘I show my brothers and sisters what they can’t see and give them hope and comfort.’ Sunlight is shining on the screen every few seconds.

Forever 27 club

Schnabel had previously made a biopic about ‘a contemporary Van Gogh’: his friend Jean-Michel Basquiat, who died too early. A boy from the street who became world famous as an artist before he died from a drug overdose at the age of 27. Other troubled artists often put on a pedestal because of their early deaths are Ian Curtis (23, suicide), Kurt Cobain (27, suicide), and Amy Winehouse (27, alcohol poisoning). The main difference is that their ‘eternal youth’ seemed to be a result of a struggle with their early-achieved fame, whereas Van Gogh suffered from a lack of recognition and loneliness.

Kitschification

In 2020, it seems not the misunderstood lunatic, but rather Van Gogh’s posthumous success is embraced by the public. The loner who turns his back on the world has become a friend to everyone; he is embraced as the Son of God, a winner whose memory continues to have lasting economics effect. Van Gogh is public property from which everyone can obtain a relic on their mantle: a wish that the Van Gogh Museum, which has been so actively contributing to the kitschification of the original work, is now also willingly facilitating.

Van Gogh is big business

Van Gogh is big businessFor example, in collaboration with a women’s magazine, the webshop offers ‘a nice foldable vase’ next to a ‘colorful tableware inspired by Van Gogh’s rustic brush strokes’. You can have a print on canvas on your wall for not even 50 euros. For those who want to get even closer to Van Gogh, a limited edition of counterfeit Van Gogh sketchbooks in a walnut cabinet is available for €6,000.

Van Gogh is public property from which everyone can obtain a relic on their mantle

Read the farewell interview with the retiring director of the Van Gogh Museum in NRC-Handelsblad, who equates the Museum with a ‘top company’. And read the welcome interview with the new director, whom Van Gogh describes in the same newspaper as ‘a brand, a brand in itself’. According to her, the question is how ‘to market this in the future’. Her predecessor cited Van Gogh’s perseverance and vision as reasons for national pride in terms of content: ‘that feeling that persistence pays off’. Winners, that is what today’s society is focused on.

The façade of the Van Gogh Museum when Ajax was honoured as national champion on 16 May 2019

The façade of the Van Gogh Museum when Ajax was honoured as national champion on 16 May 2019Against this background, it is hardly surprising that the Van Gogh Museum elevated those other heroes and marketable high earners to the status of artists. ‘Van Gogh cheers for the new Dutch Masters’ was written on the façade of the Museum when Ajax was honoured as national champion on 16 May 2019 at the Museumplein in Amsterdam. The accompanying self-portrait of Van Gogh looked remarkably stoic.

Today, the public determines what art is and what is considered to be meaningful. And Van Gogh has an audience. In this way, we can be sure that our contemporary, ‘original’ Van Gogh’s – the misunderstood madmen that work counter to the mainstream and can not or do not want to keep their heads down and obey to societal norms and expectations – will once again be overlooked.

Movies about Van Gogh that were discussed:

- Lust for Life (1956, Vincente Minnelli)

- Vincent & Theo (1990, Robert Altman)

- Crows from short story collection Dreams (1990, Akira Kurosawa)

- Van Gogh (1991, Maurice Pialat)

- Loving Vincent (2017, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman)

- At Eternity’s Gate (2018, Julian Schnabel)