At the turn of the 20th century, the quaint fishing village of Volendam transformed into a bustling artists’ colony, attracting painters from around the world with its enchanting opal light. In The Discovery of Holland, published only in Dutch for now, Jan Brokken explores this vibrant era, revealing how Hotel Spaander served as a creative hub for artists like Fritz Thaulow and Elizabeth Nourse.

Without prior information, anyone picking up a copy of The Discovery of Holland for the first time could get the impression the title sounded a little overblown: you might wonder what there could be to explore in a flat polder landscape around 1900. Quite a lot, according to the latest book by ex-journalist and master storyteller Jan Brokken (b. 1949). A colour, for example, magenta. The mother-of-pearl light of the Zuiderzee. And the tranquillity of a village on the outskirts of a world that would become increasingly hectic.

This chronicle of time travel was spawned by a visit Brokken once paid to Hotel Spaander together with the poet Hans Tentije. Tentije’s fascination with the Norwegian painter Fritz Thaulow, who worked in Spaander and died there in 1906, is our introduction to the book. From 1881 onwards, a veritable artists’ colony had developed in and around the hotel. This was not an organically grown experiment – such as in Barbizon, Pont-Aven, or Wechelderzande – but the business plan of one Mr and Mrs Spaander, who enticed painters and other visual artists to come to their picturesque village from the outset of their enterprise.

Their establishment soon numbered seventy-eight beds; Eleven studios were built at the rear. The painters and occasional sculptor or photographer usually stayed for a few weeks or months, barring the few exceptions that spent part of their lives there, ranging from three to seventeen years. The latter was the case for the Frenchman Augustin Hanicotte, who married one of the Spaander daughters and played Sinterklaas in the village.

Interior of Hotel Spaander

Interior of Hotel Spaander© Wikimedia Commons

In the summer of 1895, the American painter Elizabeth Nourse found the hotel too crowded for comfort. No fewer than thirty-two colleagues had settled there, including a dozen compatriots, as many Britons, and eight women. About fifteen hundred artists appear in the guest books, many of whom worked as if possessed. They bought their paint tubes opposite the hotel at The Art Store, the shop owned by that other industrious merchant Jacobus Simons.

A veritable constant stream of painting activity appears to have occurred, especially between 1895 and the First World War. In 1980 there were more than a thousand seascapes, landscapes and portraits hanging on the hotel walls, and the number of works from Volendam that are now in other collections and museums cannot be counted. Oh yes, the fisherwomen with their cute billowing lace caps on the cover were painted by Nourse.

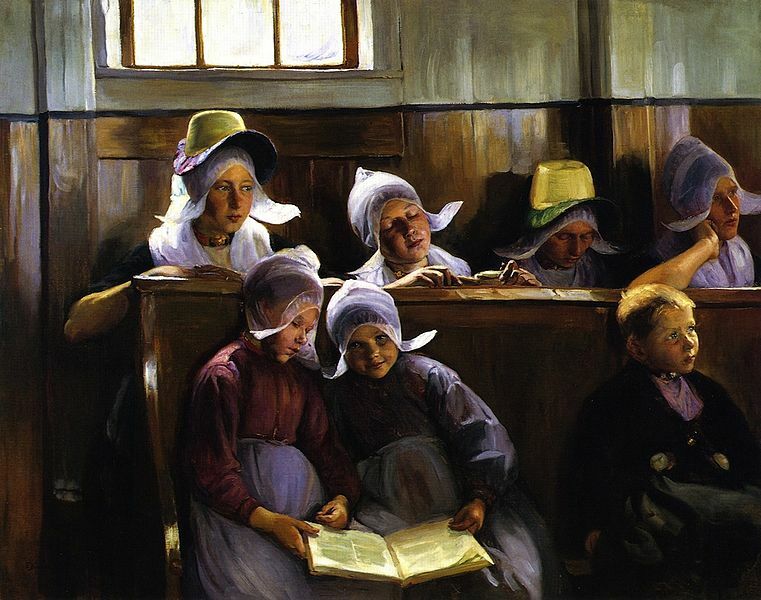

Elisabeth Nourse, The church at Volendam, ca. 1910

Elisabeth Nourse, The church at Volendam, ca. 1910© Wikipedia

Thaulow and Nourse are two of the hotel guests with whom Brokken launches into his story, but the list of artist names that parade seems endless. Of course, many second-class painters also worked in Volendam; nonetheless, it’s almost always worth googling their work as well. What is special is the huge density of great masters who have taken the village to their hearts: in random order, I mention Whistler and Toorop, the Frenchmen Signac, Renoir and Pissarro and the writers Marcel Proust and Frederik van Eeden – the former characterised Prinkher’s daughter Wilhelmina as a délicieuse,

for the latter everything in the hotel revolved around “money and flirtation, far beneath the hale and hearty atmosphere of the villagers”. In any case, they saw no problem with the dealings of their artistic guests, who in turn were pleasantly surprised by the Dutch tolerance.

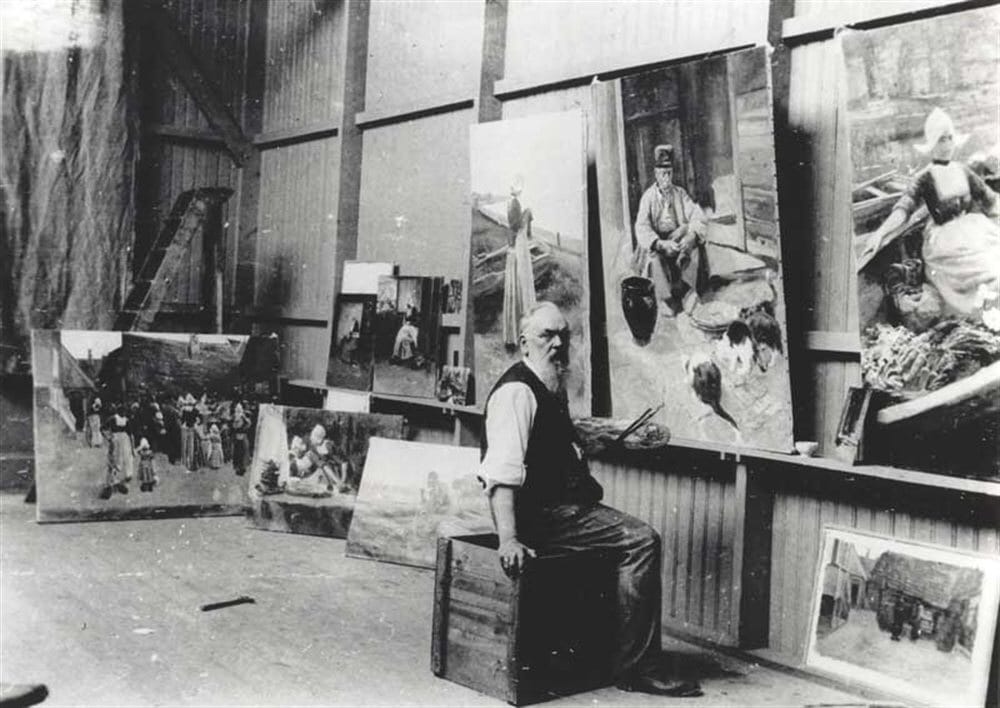

Fritz Thaulow at work in Volendam

Fritz Thaulow at work in Volendam© Wikipedia

Along the way, of course, we run into a lot of Belgians from the periphery of the Brussels artists’ circle Les XX, especially the pointillists Henry Van de Velde and Théo van Rysselberghe, who stayed in Hotel Spaander three times. Their fellow painter Frantz Charlet visited for at least six summers between 1888 and 1913, and Henri Cassiers too was besotted with the place.

The skittish symbolist William Degouve de Nuncques, a good friend of Toorop and Thaulow’s, had no use for what he saw from the window of room seven: the light was too light, the village too real. Volendam and symbolism were not compatible. Figures such as Gustave Flasschoen, Anna De Weert and Léon De Smet, appear to round off the Belgian delegation, but Brokken’s claim that “practically all contemporary Belgian painters of any importance lodged in Hotel Spaander” is a distortion of the truth.

The villagers saw no problem with the dealings of their artistic guests, who in turn were pleasantly surprised by the Dutch tolerance

The foreigners were the ones who truly fell in love with the village, which was relatively close by and yet looked exotic. Willing models posed in local costumes for scenes that exuded authenticity and simplicity. They were images of a disappearing world, far from the decadent big city. Even the stench of rotting fish was picturesque. Volendam seemed to be an icon of peace and safety in anxious, angry days. For Jan Brokken that also applied to the times of corona and the threat of war.

But even more than the cosy, all-too-atmospheric couleur locale that attracted the lesser masters in particular, was the vast expanse of opalescent light that was reflected on the surface of the water. In Volendam, the sun does not set over the sea but over the land. All of that produced, yes… a sea of light. Just ask Joseph Beuys, who grumbled that the Dutch mania for land reclamation after the Second World War has nullified the blaring light of the previous centuries, making it duller and more uniform. The local painters’ colony thus marked the end of an era.

And a colour that seems to come from just as far away: magenta, which is so difficult to define, which is a purplish red or a reddish kind of purple, “a mauve bordering on crimson”. It is the hue of the sails with which the fishing boats were rigged. It keeps popping up in Volendam’s paintings among the hundred gradations of blue – from pale, to grey, greyish, sparkling, triumphant, glaring, “as if it were a drug”. Simons sold just as many tubes of magenta as he did of his basic blue.

The Discovery of Holland is a rich and enlightening book, in which the author guides us into a small but exciting world as well as puts lesser-known artists in the spotlight. Still, the fact that it does not contain an index of names is incomprehensible: it could also have turned this beautifully illustrated story into a reference work. That said, Brokken did make generous references to his sources. Charming anecdotes liven up the lyrics – what the pop song ‘One Way Wind’ by The Cats has to do with Volendam, is something you must look up for yourself.

And what about that overblown, somewhat presumptuous title? It’s perfect in fact, because Volendam acts as a pars pro toto here. On their way to the village, the artists saw all those typical Dutch motifs pass in revue: vast skies, unusual costumes, and liquid light. And they often combined a trip to Volendam with a visit to the museums where Frans Hals and all those other old masters were waiting for them. They deserved a life with that.

Jan Brokken, De ontdekking van Holland, Atlas Contact, 2024, 320 p.