Voyage Around the World on Sandals

On the eve of the First World War, three Dutch friends believed they could make the world a better place by walking around the globe and propagating socialism in Esperanto. Naïve? Perhaps, but appealing, to say the least.

Anyone passing by the Dam Square in Amsterdam on July 16, 1911, was an unwitting spectator of an unusual procession. At its head walked a man with a sign in his hands which read “The World Walkers” in big letters, as if announcing some circus act. Behind him walked three young men, on sandals, with walking sticks, a hat on their head and a green sash across their chest again with those words: world walkers.

There was a big chance you stood there in amazement wondering what it all meant, and that was exactly what was intended since Bram Mossel, Frans van den Hoorn and Gerard Perfors, as the three of them were called, had not only planned to walk around the entire world in eight years, but also wanted to sell picture postcards with their portraits on them. So naturally, it would be better to look a little extravagant.

The world walkers at the Three Border Region in Vaals, the place where Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands meet.

The world walkers at the Three Border Region in Vaals, the place where Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands meet.© archive Bram Mossel / Querido

Bram, Frans, and Gerard called themselves idealists. They did not eat meat or drink alcohol, believed in pacifism and the socialist utopia, and hoped on their walk around the world to achieve their task with Esperanto, the world language invented by the Polish Jewish eye doctor Leyzer Zamenhof a couple of decades earlier on the premise that people would forget their national differences if they spoke a common language.

Seeing the world was not their only intention, they also wanted to write articles about it, so that Dutch readers could come to know what other cultures looked like. After all, at the outset of the twentieth century, the world was a bigger place than it is now. People hardly ever left their countries of birth and anything they may have known about foreign countries was hearsay. Incidentally, the same also holds true for the walkers themselves, who had never crossed their native borders. They had not evening camped out or gone on any long walks. This of course resulted in all of them quickly being saddled with a host of huge blisters.

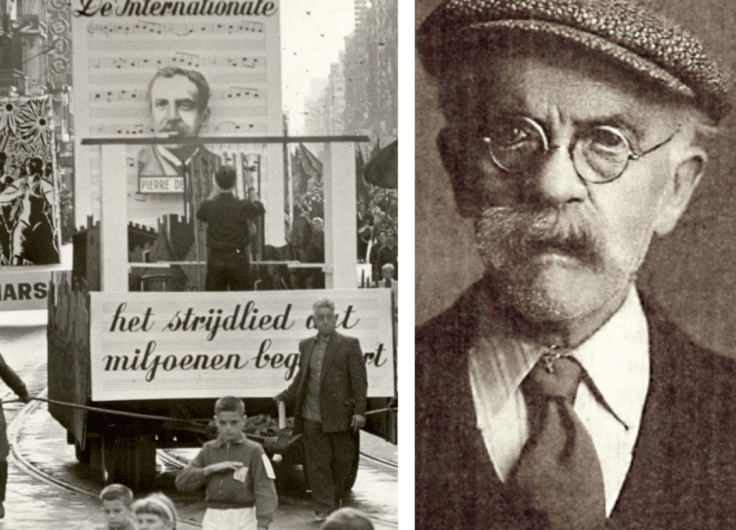

World walkers Gerard Perfors and Marie Zwarts in the Balkans in 1912

World walkers Gerard Perfors and Marie Zwarts in the Balkans in 1912© Jewish Historical Museum

The historian and writer Wim Willems tracked down the story of the world walkers after being contacted by a female reader. He had written a newspaper story about the Perfors family, his mother’s family, and the reader had immediately made the connection with Gerard Perfors. She had a suitcase in the attic full of material about the long walk Gerard had once undertaken, she told Willems. Seeing as how he was a distant relative of his, it would undoubtedly interest him. Which it did indeed.

Wim Willem’s cleverly composed, imaginative and easy to read The World Walkers provides a fascinating portrait of Bram, Frans and Gerard and places them in a world that stood on the verge of a major change. On the one hand, there was a universal buzz about the promise of socialism about which the three walkers were so enamoured that six years later would result in a veritable revolution. However, over and against that rosy vision of the future, there was also the Central European reality, with a Habsburg Empire on its last legs and an Ottoman Empire that was not that much better off either. In Vienna and Budapest, the walkers were stunned by the ethnic tensions among the several peoples who were only in agreement on one thing: that something had to be done about that Jewish scum. And in the Balkans, they nearly had to end their journey because of civil wars.

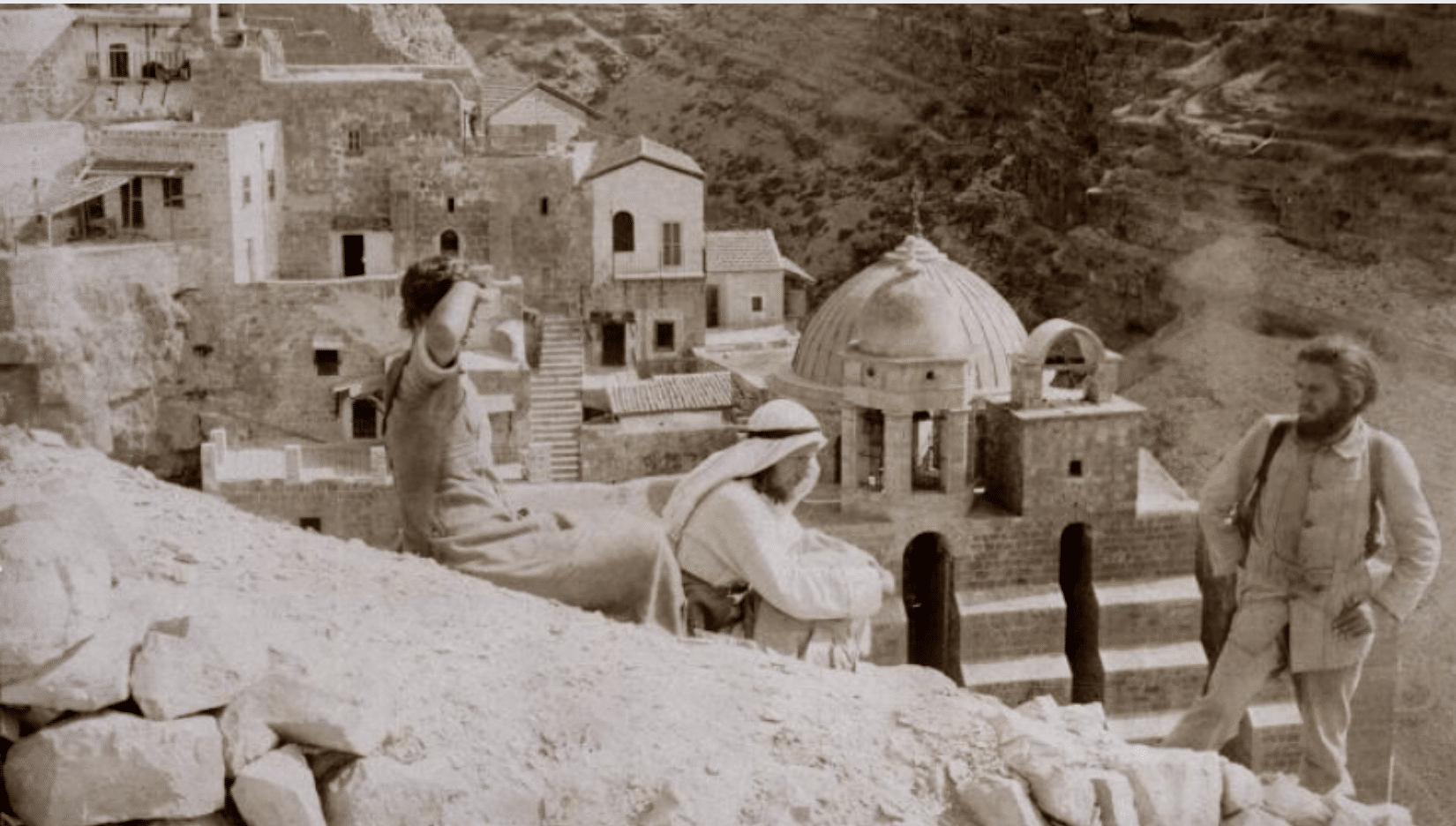

The world walkers near the Greek Orthodox cloister Mar Saba, northwest of Bethlehem

The world walkers near the Greek Orthodox cloister Mar Saba, northwest of Bethlehem© Jewish Historical Museum

But it was also a world that did not hold much promise for working-class sons such as Bram, Frans, and Gerard. You learned a trade and worked for the rest of your life for a boss. That is just about what it came down to. That things turned out differently for the three men in his book, is not just because of their bright-eyed curiosity according to Willems, but also because of the people they encountered, such as the innovative Dutch teacher Jan Ligthart, who Frans went to school with, and Dutch poets Herman Gorter and Henriette Roland Holst, whose readings Gerard attended.

Intellectuals gladly took on public roles and were not at all averse to personally receiving people. Thus, on the first evening of their journey, the three world walkers paid a visit in Hilversum to Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis, the man who had made the socialist movement so big in the Netherlands. The following day they were received in Soest by esquire Felix Louis Ortt, the leader of the vegetarian movement in the Low Countries who following the example of Leo Tolstoy advocated a sober life, took a bath every day in the tub on his balcony and believed alcohol only led to sexual excesses, that it stood in the way of moral upliftment and therefore was something better avoided.

The three world walkers with an Arab on the Mount of Olives near Jerusalem, ca 1913-1914

The three world walkers with an Arab on the Mount of Olives near Jerusalem, ca 1913-1914© Jewish Historical Museum

It was a puritanism the three walkers enthusiastically embraced from Ortt and made them write with abhorrence about Budapest as a den of iniquity. Only at the time, there were no longer only three walkers, but four, since Marie Zwart, Gerard’s girlfriend, had joined them in Vienna by train after eight months.

In the end, the four walkers did not really see all that much of the world. Their journey stopped in Palestine in 1913, where Gerard and Marie went to live in Jerusalem and Bram and Frans found a place in a Jewish colony where in no time, they turned into fervent Zionists who abandoned their pacifist beliefs declaring it was better to take direct aim at an attacking Arab rather than to one side of him. Marie, Gerard, and Bram returned to the Netherlands when the war broke out a year later. Frans lingered there too long and was stuck in Palestine, where he would ultimately start a family with a Russian Jewess and where for the rest of his life, he would make a living as a gardener.

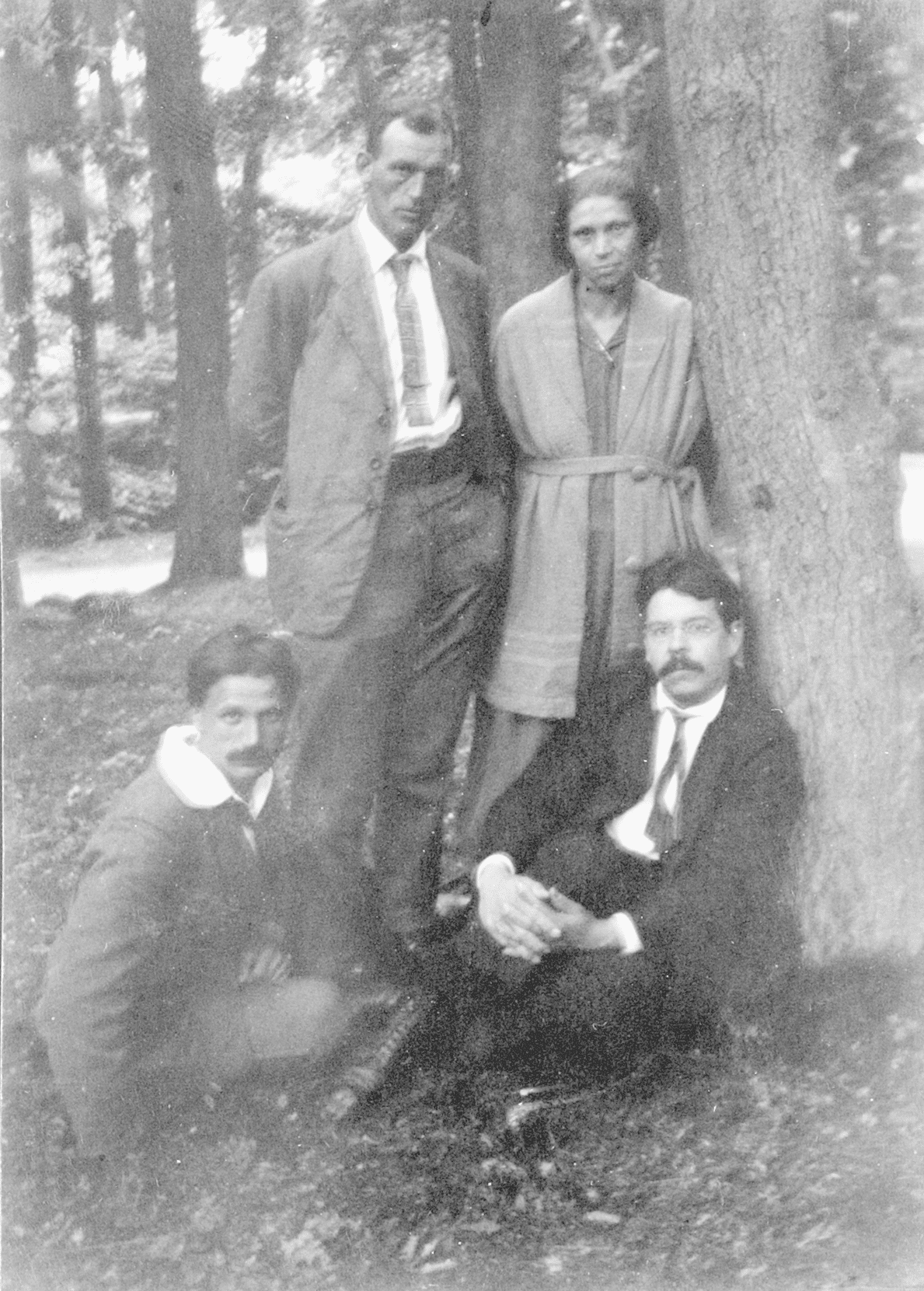

The world walkers reunited in the Netherlands, in 1923

The world walkers reunited in the Netherlands, in 1923© archives Bram Mossel / Querido

Frans would go back to the Netherlands for a final visit, Willems writes, who follows the world walkers until their deaths and who even paid visits to their children in Israel and Australia. Frans went in 1923 to see his friends and family. It resulted in the most expressive photograph from the lavishly illustrated book that is dedicated to him. Frans looks ten years older than his actual age, Marie is leaning diagonally against a tree, looking so decrepit she would probably have fallen over without that tree and Gerard stares blankly into the distance. “Sadder but wiser,” writes Willems, who remarks that the photographer Bram is the only one who looks like he could jump to his feet at any second, even though that probably had more to do with keeping an anxious eye on the self-timer on his camera.

Still, Willems does not want to call the world walker’s adventure a failure. He admires their idealism too much for that. Many of the ideals they strove for – and which during their travels regularly resulted in a hostile and sometimes downright violent reception – are commonplaces today. They may indeed have come to pass without them, but not in the end without all those other idealists who changed the world for the better.

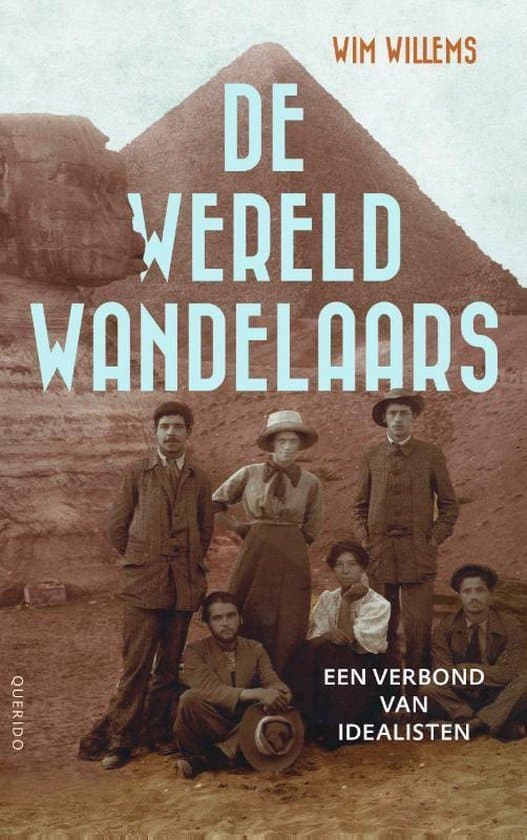

Wim Willems, De wereldwandelaars. Een verbond van idealisten (The World Walkers. A union of idealists), Querido, Amsterdam, 2020, 384 pp.