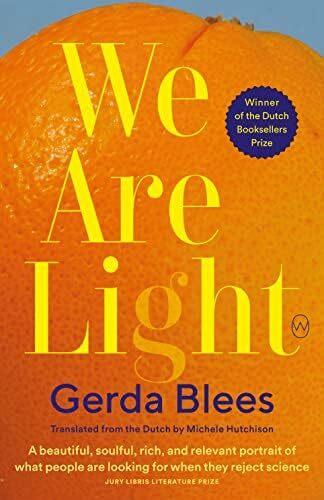

‘We Are Light’, the Prize-Winning Debut Novel by Gerda Blees: Circling above Good and Evil

A simple press report about a death in a commune inspired Gerda Blees to write We Are Light, a story about how ideals can bring out both the best and the worst in humankind. Blees won the EU Prize for Literature with her debut novel and has been nominated for the Dublin Literary Award 2025.

The key to a good novel? Not the plot, not the characters, and perhaps not even the narrative style itself. Indeed, according to author and poet Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer, who appeared on the Dutch television programme Summer Residents (Zomergasten) in 2020, the key to producing a good novel can be found in the setting. There are perhaps only a few authors who would confess to this so openly but, for many novels, it certainly holds true. It is often the first thing a reader remembers, as they pluck an almost forgotten book off the shelf and try to recall what it was all about.

Gerda Blees

Gerda Bleesⓒ Bartjan de Bruijn

The setting in We Are Light, the debut novel by Gerda Blees (1985), will certainly stick with us. In the summer of 2017, Blees, who previously published short stories and poetry, read about the death of a woman in a commune in Utrecht. She went on to read more articles about this suspicious death, browsed the website of the commune, before subsequently allowing her imagination to run unbridled with the story. By digging deeper into the background of the Sound & Love (Klank & Liefde) commune, this ostensible fait divers was seized upon in order to grab today’s world by the scruff of the neck.

In addition to this singular setting, Blees employs an innovative technique that characterises the identity of the book. She tells her story not simply chronologically or from the perspective of one of the residents, or a researcher, but changes the narrative perspective in each chapter. The characters who get the chance to speak are sometimes the most obvious choice, such as the leaders of the commune, but, in many instances, they are not.

It is the night that begins the story; the night that is usually so reluctant to reveal its secrets, speaks on this occasion openly about the last breath of the emaciated Elisabeth, while her equally thin sister Melodie and their friends Muriël and Petrus watch on. The night leaves the reader feeling that something must be wrong here, for no normal person reaches the end of their life so skeletal.

Following this, twenty-four other narrators take over the story. The scent of an orange. Two cigarettes. A lonely cello. A pair of goat wool socks. But, also, the parents of Elisabeth and Melodie, and the commune Sound & Love, as the foursome referred to itself. From each of these perspectives, Blees is able to circle around her subject matter and to approach it from every conceivable and unconceivable angle possible.

From 25 different perspectives, Blees is able to approach her subject from every possible angle

This also means that Blees frequently adjusts her narrative style. This produces many a moving and beautiful passage, written in poetic prose, in which Blees demonstrates what an engrossing storyteller she is; a writer with empathy and an eye for meaningful detail. This is the case, for example, in the chapter in which Elisabeth’s body is being examined by the pathologist in the moratorium. Heart-breakingly beautiful. Or in the touching final chapter, in which the light itself takes over the narration.

The changing narrative style is both the novel’s greatest strength and its weakness, as not all twenty-five passages are equally compelling. When Blees plays with the clichés uttered about the commune by their working-class neighbours, it remains humorous. But, in the chapter in which we read along in the WhatsApp group belonging to the two brothers and the sister of Elisabeth and Melodie, we are offered little more than an appetiser that seeks to summarise all that came before it. Here, all the irony, the playfulness, the subtle layers, are as good as gone. In a different chapter, Blees produces yet another summary but this time in a hilarious and self-critical manner, as the story itself becomes the storyteller. A novel cannot get much more meta than this. The story makes a bet on how it will end (gambling on an anti-climax) and complains a while not only about the flawed writer, who deliberately pens unsatisfactory and ambiguous storylines, but also the reader, who is also partly responsible for all the confusion that story is facing. If only we had not allowed our thoughts to go astray or tried to read between the lines!

But reading between the lines is simply what a reader likes to do; searching for the deeper meanings in a story, which are shown but not literally described. This is how We Are Light becomes a book about how ordinary, simple people try to create a better world for themselves and their loved ones: about idealism, believing in good, and wanting to do everything to achieve that good for you and the people around you. To create a close-knit group, a place where you are at home.

But even well-meaning people, or perhaps especially well-meaning people, can be misled, dragged along by their faith in another more beautiful, gentler, world. They can deceive even themselves and if self-doubt does strike, it is often too late. Then you have dreamed of a better world, but you end up on an uncomfortable airbed in a commune and, then, on a hard bunk in a police cell.

For the pursuit of goodness can also turn into compulsion, abuse, psychological terror. Blees does not write it but guts it and goes in search of explanations. She finds these both within the community, as well as in the commune itself. Our desire to be better than others, sometimes makes us bad. Blees doesn’t judge but shows very clearly, and always with a note in the margin, that things can be different from how we experience them ourselves. For what is reality for the police inspector, is not at all the reality experienced by Elisabeth. In this way, there may be a happy ending after all: both for the leaders of the commune, as well as for the rest of the world.