We Have Been Laughing at the News for Three Centuries

Parodying messages that make fun of the news are a typical phenomenon of today’s online culture but, in the Netherlands, people have been laughing at current events for more than three centuries. From the Haegse Mercury in 1697 to De Speld in 2022: how daring is Dutch satirical news?

‘Instagram gives all teens 50 extra likes to raise their self-esteem.’ ‘Nobel Peace Prize awarded to two journalists who get to fight it out.’ ‘Shutting the rubbish bin on the train caused a big bang.’ These are just a few examples of headlines recently sent out into the world by the satirical news website De Speld. You may have come across them on your favourite social media site and paused to smile or chuckle before you quickly scrolled to the next startling or comical message.

De Speld and its many clones in The Netherlands and Flanders – for example, De Gladiool, Nieuwspaal, De Raaskalderij and De Korrel – are tailor-made for today’s meme culture. Memes are short and easily imitable “jokes,” often with a strong visual and intertextual component. They circulate endlessly on media such as Instagram and TikTok. Two qualities shared by almost all memes and De Speld headlines: a) they are meant to provoke laughter, and b) they are understandable at a glance. Humour and speed are, therefore, the keywords.

Screenshots from the satirical news site De Speld

Screenshots from the satirical news site De Speld© De Speld

Interestingly, the phenomenon of satirising current affairs actually started long before the Internet era. Since the early eighteenth century, regional periodicals have been attempting to make readers laugh at the news. But to what extent can a direct line be drawn from these eighteenth-century predecessors of De Speld to the present? And what is it about that combination of humour and current affairs that keeps us coming back for more?

Quick little belly shakers

Before I answer those questions, let’s take a quick look at the current situation. In the Netherlands, the website De Speld, founded in 2008, dominates the online news satire landscape. Several articles appear daily, as well as regular videos and podcasts. De Speld has more than half a million followers on Instagram alone. In Flanders, the offer is more varied. There, lovers of satirical news can choose from De Raaskalderij, Het Beleg van Antwerpen and De Korrel. Both the Flemish sites and De Speld are loosely based on The Onion, an American satirical news project founded (print) in 1988 and online since 1996.

Though all of these sites have their own style, there are a few key similarities they share. The first is that, while the published news items are clearly fictitious and recognisably untrue, they do coincide with real news events. While it’s true that Instagram hasn’t really given fake “likes” to teens, this social medium is notorious for the negative impact it can have on teens’ self-esteem. The De Speld article plays with that – supposedly known – fact.

All the sites have an element of parody, imitating the style and rhetoric of “serious” news media in a humorous manner

Second, all the sites have an element of parody, imitating the style and rhetoric of “serious” news media in a humorous manner. Take, for example, the phenomenon of ‘the expert’ flown in by newspapers and current affairs programs to provide the necessary interpretation and explanation of the news. Such a figure regularly returns on De Speld in the capacity of the fictional character Bert Bokhoven, who is sometimes an economist and sometimes a traffic expert. The format of the headlines on satirical news websites is also clearly copied from mainstream journalism, often with a suggestion of breaking news, as in this headline from De Raaskalderij: ‘Scientists warn of rising numbers’.

A final similarity between these sites is that they are deliberately aiming for a quick smile. It is often clear from the headline alone what the joke is and that is a clear difference in comparison with satirical programs on TV, such as De Ideale Wereld (The Ideal World) in Flanders or Even tot Hier (Just till Here) in The Netherlands, which require viewers to take at least a few minutes to work out a joke. Satirical news sites thrive in today’s Internet culture largely thanks to their ability to get readers shaking with laughter within seconds.

Terribly dead

But the eighteenth-century predecessors of De Speld

were no less pointed in their humour.

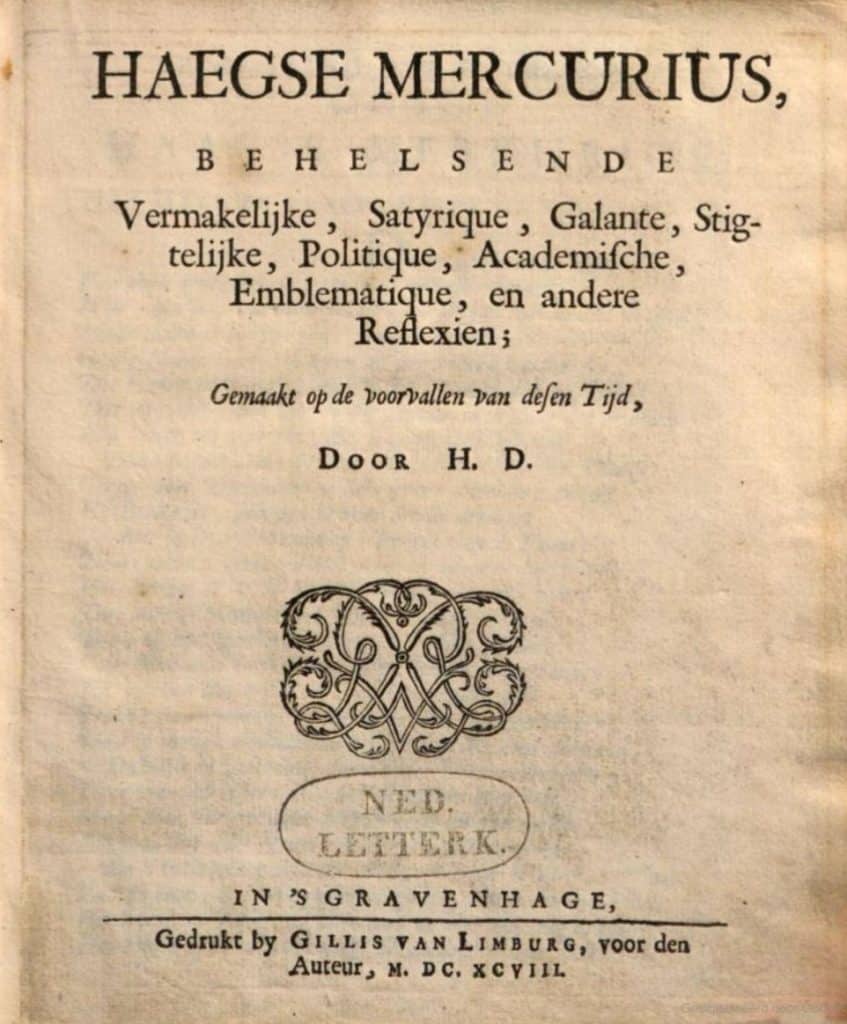

On 7 August 1697, the very first Dutch satirical magazine rolled off the press. It is not surprising that this happened in The Hague, which was already the political centre of the Netherlands at the time. Haegse Mercurius was the name of the magazine, and in the following two years it would appear no fewer than twice a week, every Wednesday and Saturday. In Roman mythology, Mercury was, among other things, the messenger of the gods, and thus a sort of newscaster or reporter. For this reason, his name often appears in the titles of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century newspapers. Haegse Mercurius

actually means something like The Hague Messenger or The Hague Reporter.

All the articles in the Mercurius were the work of only one author, the former lawyer Hendrik Doedijns (ca. 1659-1700). His style was, in some ways, surprisingly modern. For example, the pieces in his magazine mainly consisted of short, comic anecdotes that referred to current political events. In episode two we read: ‘The Ridder play in Dusseldorp started under the blue sky as well as under the covers,’ an allusion to sexual activity that needs little explanation even three centuries later.

Many other titles soon followed the Haegse Mercurius in the Dutch language regions. Not all of them were as astute as Doedijns’ magazine, but they all focused on current events and were designed to make readers laugh, just like the original. The magazines of Jacob Campo Weyerman (1677-1747) were extremely successful, but unfortunately quite unreadable for a contemporary audience. He was responsible for as many as fourteen different satirical magazines between 1720 and 1737, and eventually ended up in prison on justified charges of blackmail.

The eighteenth-century satirist Hendrik Doedijns uses a style that was surprisingly modern

More accessible to modern readers are the somewhat farcical observations of Jan van Gijsen, who presented his Amsterdam Mercury

to the public every Monday for no less than twelve years, from 1710 to 1722. Van Gijsen’s lyrical pieces were written completely in rhyme. For example, in response to the death of the famous French monarch Louis XIV in 1715, he wrote:

En op September een was Koning Lodewyk,

’s Morgens voor ’t Klokslag van halfnegenen een Lyk,

En heeft ten laatsten eens de laatste snik gegeven,

Na bykans Seventig en zeven Jaar te leven;

Daar lag die Wareld Vorst dien Lodewyk de Groot,

Dat wonder van zyn tyd, helaas! harsteeke Dood.

(And on September one was King Louis a corpse,

In the morning before the stroke of half past eight.

And at last he gave the final gasp,

After nearly seventy and seven years of life;

There lay that Prince of the World, that Louis the Great,

That wonder of his time, alas, dead as a doornail!)

It is easy to imagine how the Amsterdammers of 1715 chuckled when they read such a passage while on their daily visit to the coffee house, where such magazines were available.

Laughter was suspicious

Do the magazines of Doedijns, Weyerman and Van Gijsen form a kind of Speld avant-la-lettre and is there therefore an ongoing tradition? Yes and no.

They certainly show that poking fun at the news has a long history. They also show that, then as now, those in power are ready subjects of ridicule, and, as a result, jokes about the news often have a critical edge: the person to whom the barb relates is symbolically laid bare and his/her power and/or influence potentially undermined.

Do magazines like 'Haegse Mercurius' form a kind of 'Speld' avant-la-lettre? Yes and no

At the same time, there are also many differences. To begin with, “made-up news” was rare in the eighteenth century. The variety in the formats is also significant. Insofar as we can in a general sense compare Doedijns and Weyerman with contemporary satirists, we should rather think of comedians or columnists: one author, with a clearly recognizable profile, giving a personal opinion about current affairs and making full use of comedic means.

In addition, the reach of satirical news is, of course, much greater today than it was in the eighteenth century. The number of De Speld’s Instagram followers contrasts sharply with the circulation of no more than 500-1000 copies that Doedijns probably printed. Both he and Weyerman were also quite elitist: their texts are full of classical references that only a thoroughly trained reader of Latin could follow. This means that simple craftsmen and women were by definition excluded from the direct readership, because they had no access to such training.

Finally, the status of humour itself was completely different in the 18th century than it is today. As a New Zealand media scholar aptly put it a few years ago, humour is much more a requirement than an option in Western society today. Both the ability to appreciate all forms of humour and to actively use it are talents that anyone who wants to participate in this society must have. Humourlessness is a sin. Anyone who publicly questions the humorous aspect of certain (stereotypical) jokes, even in this politically correct age, can expect fierce resistance.

Three centuries ago, attitudes towards humour were quite different. While humour was widely practised, it was also somewhat suspect. Laughter has traditionally been associated with the devil. In principle, jokes could only be used for useful purposes, such as conveying a moral or enlivening social interaction. Humourists like Weyerman liked to claim that their pranks served an edifying purpose, although in the light of the excess of entertainment and the scantiness of real “lessons,” that claim is somewhat implausible.

Humour is much more a requirement than an option in Western society today. In the past, laughter has traditionally been associated with the devil

In such a context, satirical news publications fulfilled a distinctly different function than they do today. Then, it was audacious, suspect and disrespectful to talk comically about the serious world of politics and administration. Authors who did this were taking a risk. Now, satire fits seamlessly into a media-flooded society entirely driven by entertainment and sensation, where everything and everyone seems subordinate to the power of the algorithms. The greatest risk in the Low Countries today is not to end up in jail, but to lose followers and attention.

Everlasting source

The latter, of course, does not detract from the pleasure that readers, then as now, derive from satirical news media. Perhaps the most important constant in more than three centuries of “laughing at the news” is that political and social events are an inexhaustible source of inspiration for creative humourists. Take one or more recent news events, add a comical tweak such as inversion, exaggeration or pastiche, and voilà: a satirical article is born.