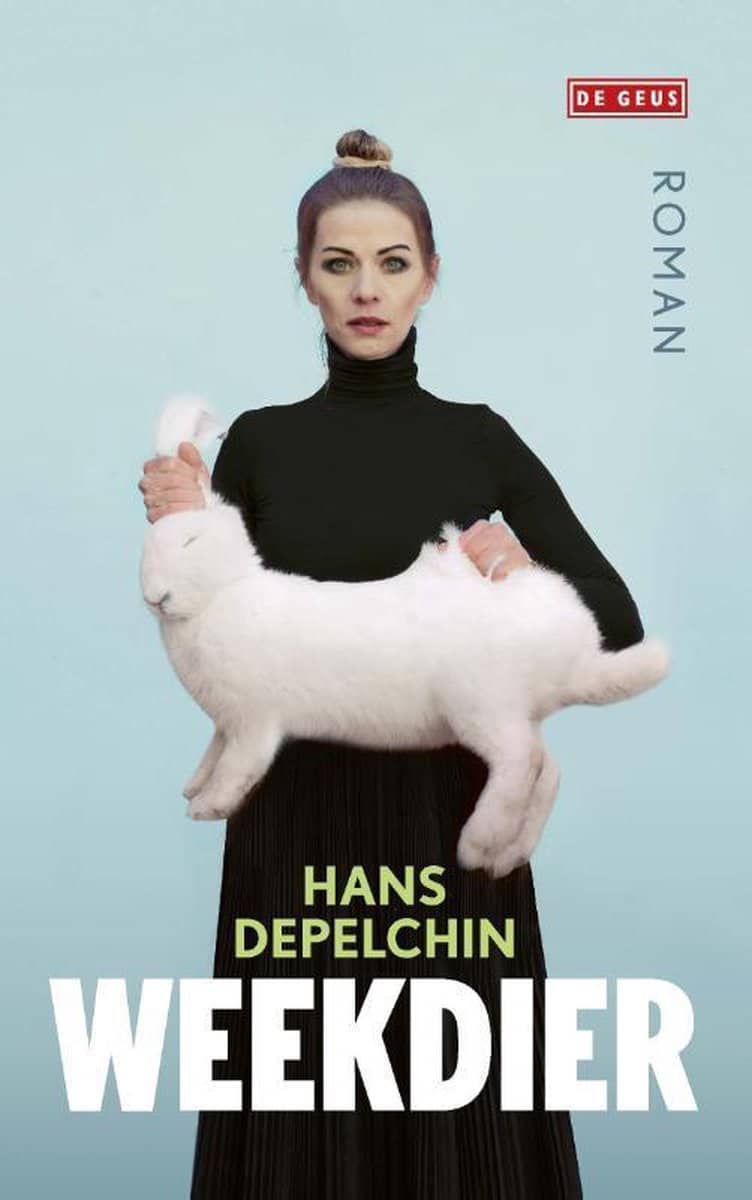

‘Weekdier’ by Hans Depelchin: In Search of Liberation Through Art and Sex

They are a colourful and curious bunch, the artists that Hans Depelchin assembles in his debut novel Weekdier (Mollusc). All are at a crossroads in their lives.

In a cellar that smells of fresh plaster and wet dogs, a group of artists has come together for a farewell ritual. There is an urn, whose maker sits proudly in the audience. On stage is an actor in the nude, who has a milky complexion and compact breasts. Behind her, a pianist is tapping mechanically. The photographer whose photos are being projected shifts impatiently on his wobbly chair in the audience.

Hans Depelchin

Hans Depelchin© Pablo Cepeda

Those present, all of them residents of Liberation Street in the trendy museum quarter, had expected some kind of happening, something pleasant, preferably with plentiful nibbles and even more drinks. Not this dramatic ceremony reminiscent of a funeral. Which does not even go quite as planned.

The prologue to Weekdier (Mollusc), by debut author Hans Depelchin (Ostend, b. 1991) already contains everything that features in what follows: dreamy, almost magical-realist passages about artistic types who are frantically searching for the next stage in their personal life or career. They do this through bizarre art projects, or through sex, or sometimes even a combination. They are at a crossroads in life because part of the Liberation Street is up for demolition, hence the farewell in the cellar.

Not that any of the arty residents are really so close. Often the only thing they have in common is that they stick reviews of their work on their walls. Those reviews were written by Mathilde Beckers, a somewhat jaded teacher in arts education, who in her spare time is also an art critic for a reputable newspaper. Of course, Mathilde also lives on the same street. She writes about her neighbours, though she’s never met any of them.

In the following chapters, one by one, we get to know the artists and their struggles. As it is, their lives entwine, there are overlapping events, if only because the even numbers keep a close eye on those living opposite, and vice versa. Each side even has its own drinking hole. One is an everyman’s pub, the other is a cool, hipster joint. And inside, there is a lot of talk about which side of the street will eventually be the one to fall.

Depelchin switches deftly from one perspective to another, writes very humorously at times and dares to hone in on delicate subjects. Such as the hypocrisy of the free-spirited actor living with a macho columnist who writes the most reactionary newspaper columns, without any care for the woke circles in which his girlfriend moves. She is pregnant, but does not know who the father is, because as a safety net she has also taken another more liberal lover.

Depelchin writes very humorously at times and dares to hone in on delicate subjects

There is also a sculptor whose contracts stipulate that he can fuck his models too, while his girlfriend may serve as his secretary and receptionist a floor below. And a bisexual pianist who is in a relationship with a girl and her half-brother at the same time, while they cannot know about each other.

Depelchin peppers his story with references to classics, such as the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen (the text of A Doll’s House is present throughout the story) and the Swiss sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti. This sometimes lends the novel an unnecessarily highbrow feel, although fortunately, Depelchin returns to its core fairly quickly: a character sketch of people in their late twenties wondering what their next steps in life should be.

Their search – and yearning – for the ultimate freedom runs into all sorts of bourgeois stumbling blocks, as they try to find a way out. But sometimes it just depends on which side of the street you live on, because you have no control over everything in life. Not even as an artist.

Depelchin’s debut is an ambitious and richly crafted work. The writer already has a publication list as long as his arm, as a contributor to literary magazines such as Het Liegend Konijn, Kluger Hans and DW B. That experience shines through this first novel, just like his studies in modern literature and poetry. All of which makes for a sumptuous novel, in which the joy of writing jumps out from the page, and in which Depelchin steadily steers his wandering souls down towards the cellar. Ready for demolition, or resurrection.

Excerpt from ‘Weekdieren’, as translated by Paul Vincent

pp. 265-267

The buzzer of the intercom. Siffer presses the red button and hears Greet’s voice, high-pitched and businesslike.

‘Jasmin here at the desk.’

‘Who?’

‘Jasmin Van Dam. She knows you.’

Siffer scratches his goatee, runs his hands through his hair, thinks, looks at the girl sitting naked on the rug in the middle of his studio, her eyes wide open and dark brown, hair blond, almost white, a young Audrey Tautou who has bleached her hair: the eyes just as mischievous, the lips panting a little, the top one tauter than the lower one, the eyebrows long and dangerous.

Her mouth opens and she smiles with teeth that make a bigger impression than expected, almost the effect of blacklights on white stockings. She is thin, has lots of pubic hair that exceeds the bounds of the standard triangle curling enthusiastically and intensely, in the direction of a navel that is a knot and not a dish.

Her nipples are stiff with the promises she has not yet been able to keep, but which under her skin are throbbing to be made good, goosebumps of expectation. Cross-legged, her back dead straight as a Buddha.

She has it in her, but Siffer is not yet certain. He can only be certain when consent has been given and the test day is over.

Siffer does not like being interrupted by his receptionist. Normally Greet only does that in emergencies, for example if the police are at the door. And even then she usually manages to see off the uninvited guests by herself. Siffer definitely has nothing to hide, but he does not like snoopers. He wants to be able to do his work in utter serenity. There is no question of a transaction, just conviction and a quest. His way of working touches on life itself.

When Siffer is not working, Greet is his lover. Over the years they have learned that everything is possible, provided you keep things well separated, structure them, integrate them in a plan. Everything that does not fit in must be avoided. Anyone who leaves the programme, leaves the agreement, leaves the relationship, leaves and can never return. Greet and Siffer do not want to leave, so they live in the programme. The predictable peace, the reassuring framework of an Excel document.

‘Greet, I’m working.’

‘I wouldn’t disturb you if it wasn’t urgent.’

‘She can come back another time.’

‘She’s an aggressive type.’

Then in a whisper: ‘She’s torn all the pages out of your catalogue. She’s never been here before. I don’t recognise her face. Normally I recognise every face.’

The sharp smell of wallpapering glue penetrates Siffer’s nose. He looks at the iron bucket in which he has been preparing the mixture. It has been ages since he last stirred it.

The girl wobbles uncomfortably back and forth on his rug, like a fruit dish that has fallen on the floor and does not break but comes to rest rocking gracefully on its base. She turns her head towards the small windows below the ceiling, the light curtains that admit an orange impression of daylight, and then she rubs her neck with her hands. She acts as if she does not know that Siffer is looking at her. She deliberately acts like a girl who imagines she is alone. It is insufferable.

She is given support by an army of sculptures in all shapes and positions, in various stages of completion. Mnemosyne II up to and including X, not one completely finished. Mnemosyne, mother of the muses, goddess of language and memory, who has the power to make human beings forget everything.

The girl again looks straight ahead, at the workbench which is fixed to the opposite wall like an extended bookshelf. No confusion there: hammer and chisel lie neatly side by side like a knife and fork, ready to attack something. Above the workbench hangs a newspaper cutting with a review. On the corner stands the terrarium where Manzoni pads nervously to and fro, in a blue glow more reminiscent of aquariums. The stone marten is hungry and scratches intolerably at the glass with its paws.

Hans Depelchin, Weekdier, De Geus, Amsterdam, 336 pp.