What Tree Rings and Core Samples Tell Us About Our World

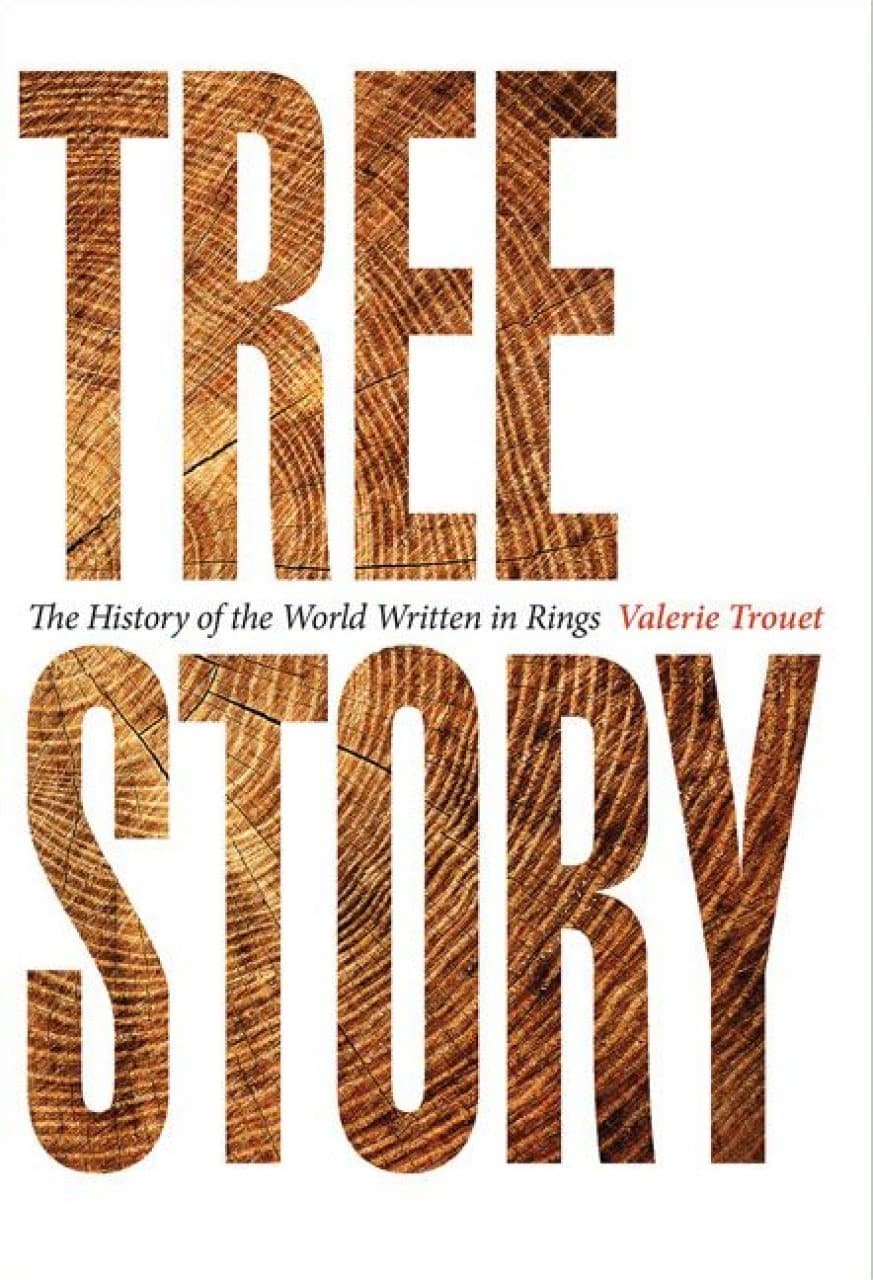

Those who know where to look can read the history of the planet and the human race in trees and landscapes. Two researchers from the Low Countries, Salomon Kroonenberg and Valerie Trouet, tell the story of the earth, our past and perhaps also our future. Trouet’s book, Tree Story: The History of The World Written in Rings, won the Jan Wolkers Prize for best nature book.

When you count the rings on the stump of a felled tree, you look back in time. Every ring indicates the tree’s annual growth. In optimal conditions, a tree grows a broad ring. The consecutive rings are like a barcode containing information about the ecological and meteorological conditions of the tree’s location over the years. The width of the ring and the characteristics of the cells from which it is composed tell a dendrologist about the amount of sunlight, the temperature and the food supply at the time. A dendrochronologist pieces together the series of rings from trees of different ages to reconstruct the climate history of entire regions and the history of forests. The longest uninterrupted tree ring archive dates back 12,650 years.

Valerie Drouet

Valerie Drouet© Koen Broos

In Tree Story, Belgian dendrochronologist Valerie Trouet, associate professor in the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona – the birthplace of dendrochronology – coaxes one fascinating story after another out of the trees. She draws on a long career involving expeditions to every continent and ground-breaking articles in prominent journals, while also revealing the history of her discipline and the work of eminent colleagues.

Wherever there is wood, there are tree rings. It is the signature of time, laid down in fossilised tree remains, stumps conserved in peat, prehistoric javelins, beams from old buildings or ships, ancient musical instruments or living trees. The oldest known living tree is a bristlecone pine that has been growing for 5,062 years in California. Dendrologists take a core sample from a living tree trunk without harming it, using a hollow wood drill. On a violin, the rings are on the surface and you can easily read them. In Stradivari’s magnificent instruments, the narrow rings of the compact wood (which contribute to their unique sound) show that they were made with material grown during the extremely cold summers of the Little Ice Age, which began around 1500 and would last three centuries. However insignificant a violin might be to the great history of the planet, its ring patterns offer additional insight into the evolution of ecosystems and the climate.

The oldest known living tree is a bristlecone pine that has been growing for 5,062 years in California's White Mountains.

The oldest known living tree is a bristlecone pine that has been growing for 5,062 years in California's White Mountains.© Chao Yen / Flickr

With the help of the rings Trouet pieces together the history of the earth, its climate and its inhabitants. She supplements the stories of the wood with complementary storylines found in stalagmites, ice, coral reefs and otoliths (from the inner ears of fish), as these other geological and biological processes also form layers and reflect history.

Salomon Kroonenberg

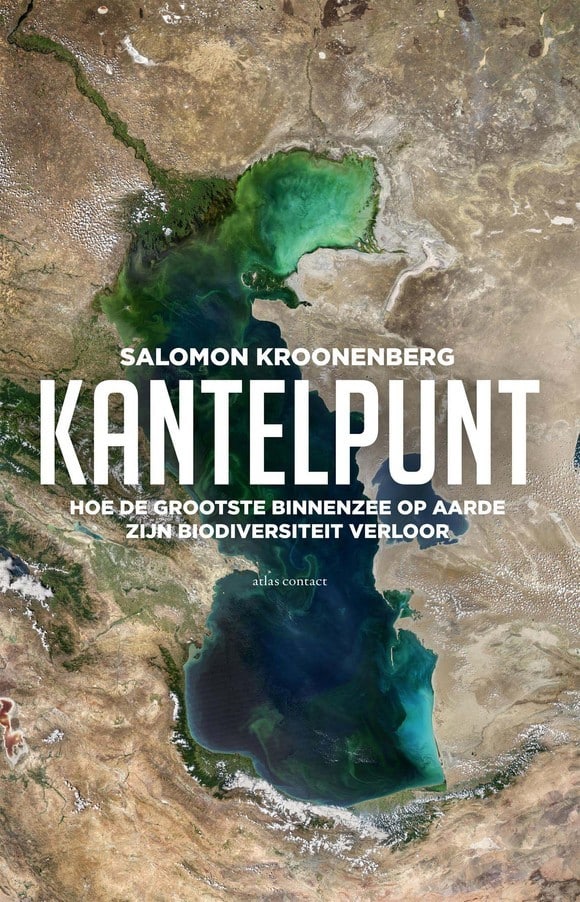

Salomon KroonenbergPondering planetary processes is something that Salomon Kroonenberg, emeritus professor of geology at Delft University of Technology, has been doing all his life. He looks at layers of earth, core samples in pack ice or growth rings in fossil shells. From his perspective on geological time, he has always been a mildly critical observer of the brouhaha around global warming and sea level rises. He is not a climate change denier, but he points out the immense changes that have taken place in the past, long before man entered the scene. His previous books, such as De menselijke maat (The human scale, 2006) and Spiegelzee (Levelling the sea, 2014), also use geological remains to indicate the tipping points in the ecosystems of seas and continents, when large parts of the flora and fauna disappeared, and new species took their places. Our species has now become a game-changer and he cautiously wonders how we should deal with a new turning point, one that we may have instigated ourselves.

In his latest book, Kantelpunt (Tipping point) Kroonenberg does the same thing as a privileged guest at PRIDE (Pontocaspian Biodiversity Rise and Demise), a European multidisciplinary research project carried out by a team of geologists and biologists from twenty different countries. They study the rise and fall of Pontocaspian biodiversity, where Pontocaspian indicates the region around and between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. The technical and intellectual work involved in understanding what has gone on there over the last 34 million years is intensive and exciting. One discovery or observation leads to another question, requiring yet another technique from another scientific discipline to answer. How can we explain the fact that the original flora and fauna of the Caspian Sea suddenly disappeared in the twentieth century? Is there a connection with overfishing and poaching of sturgeon? Do sea level rises have anything to do with it? Can prehistoric extinctions shed further light on the matter? Or is it down to recent global climate change? And how do you glean the answers from layers of earth and fossils?

The Dreissena elata (brownish mussel), one of the commonest species in the Caspian that likely went extinct in the past 30 years due to displacement by the invasive Mytilaster minimus (purple mussel) that was introduced in 1938 in the Caspian Sea.

The Dreissena elata (brownish mussel), one of the commonest species in the Caspian that likely went extinct in the past 30 years due to displacement by the invasive Mytilaster minimus (purple mussel) that was introduced in 1938 in the Caspian Sea.source © Naturalis / Frank Wesselingh

It is fact-finding of the highest order, clearly written and richly illustrated. The tipping points in the biodiversity of the Caspian Sea turn out to be a model for those all over the earth. There is no balance in nature, Kroonenberg suggests. After tectonics, rivers, the climate, the sea level and the ice ages, humans are now the latest factor in the series causing a crisis in Pontocaspian biodiversity. We are an invasive species that recreates nature, with or without climate change.

Trouet and Kroonenberg’s stories take on epic dimensions. Shifting tectonic plates, volcanic eruptions, meteor impacts, forest fires, hurricanes, floods or drought, all have left their traces in different kinds of layers. From Siberia to Patagonia, from Mexico to Cambodia, from Baku to Gibraltar, the trees, coastlines, isotopes or genetic variants recount the histories of the environment and of humans. These are stories of hunger and thirst, of the rise and fall of civilisations, and their interplay with epidemics, wars and migration, in a context of unexpected climate changes. Those changes helped determine whether societies flourished or failed due to a lack of resilience.

Deforestation in the tropical rainforest.

Deforestation in the tropical rainforest.© Earth.org

Deforestation is a phenomenon of all times. Without wood, past societies would have been impossible. Humans have engaged in clearcutting, the final episodes of which are now playing out in the tropical rainforest. That has always brought calamity, particularly when combined with pandemics and political instability. The disappearance of the rainforests is echoed in the disappearance of plant and animal species, whether or not they are supplanted by invasive species from elsewhere, which are often introduced by man.

Trouet and Kroonenberg make it clear that we are now experiencing the greatest climate change of the last two thousand years. For the first time in history, we now know what’s happening, in part thanks to the scientific research to which they bear witness. Their stories give a feel for how exciting it is to be a researcher right now. Never before did we have so much data, nor so many challenges. It’s not so much climate change itself that will determine the final result for the human race but the socio-economic and political-cultural context. In the past, too, those factors determined the impact of shifts in ecosystems that buried empires and civilisations under the geological dust.

Trouet and Kroonenberg make it clear that we are now experiencing the greatest climate change of the last two thousand years

We live in grand times, but also in the realisation of great uncertainty. Since these books were written, a new virus has emerged. That virulent organism underlines humans’ global interdependence within a complex of ecology and geology. Perhaps the way we deal with that will be legible to future dendrochronologists from the core samples of trees we’re planting now.

- Valerie Trouet, Tree Story: the History of the World Written in Rings, John Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2020, 256 pp.

- Salomon Kroonenberg, Kantelpunt (Tipping point), Atlas Contact, Amsterdam, 2019, 216 pp.