When Brussels Was a Paradise for the Colombian Elite

Between the First and Second World War, a strange kind of snobbery arose among the Colombian elite: the siren call of distant Brussels, impossible to ignore. Anyone who had the means dreamed of dropping anchor there, turning their backs on the New World and strolling along the boulevards of the Belgian capital.

Brussels had attracted international thinkers such as Baudelaire, Marx and Multatuli in times past. But after the First World War, the magnetic pull of the Belgian capital seemed to be weakening. Brussels still bustled, but it had become more provincial and anonymous. Yet even these characteristics attracted a new audience.

Though Brussels was not particularly compelling, for those who had money it was a good and pleasant place to be. The culture was Latin but in contrast to Paris, it also remained comfortingly Catholic. Belgian education was set upon a dizzyingly high pedestal: in no other foreign country were there more Colombians on school benches or in university lecture halls. Even the novel A Hundred Years of Solitude

alluded to this phenomenon when Gabriel García Márquez explains how Aureliano Segundo was ‘tormented by the fear of dying without being able to send Amaranta Úrsula to Brussels’. The girl’s mother, ‘shocked by the idea that Brussels was so close to the depraved city of Paris,’ managed to delay the parting for a while, until she could be assured that her daughter would end up in a girls’ boarding house.

Brussels stock exchange in the 1920s.

Brussels stock exchange in the 1920s.© Wikimedia Commons / source: Nels postcard company in Brussels, Ern. Thill No. 8

A respectable boarding house

It was the children of the Colombian elite who sat on those school benches, the children of businessmen, plantation owners and politicians who would one day follow in their parents’ footsteps. One of these students was the future president Alfonso López Michelsen, who reminisced in his memoirs about his years in Belgium. Why, he asked himself in hindsight, did Belgium exert such a powerful draw on his countrymen? The explanation was completely prosaic: Colombians are incorrigibly herd-driven.

‘The minute we pass beyond our own borders, into no matter which country, we go to the same hotels, we attend the same Sunday Mass in a Catholic church, we will undoubtedly gossip about the latest news from the Fatherland and, based on some invisible unifying standard, assess which are the best or worst restaurants and theatres that, in whispered word of mouth, will be recommended or disparaged. This is what happened from 1920 to 1930, with regard to the small kingdom of Belgium. The meeting place of the Colombians was neither London, nor Paris, nor Berlin, but Brussels which, to my mind, in contrast to the neon-lit cosmopolitanism of the great hotels with which other European capitals dazzled us, was like a respectable guesthouse for Christian families.’

The children of the Colombian elite studied in Brussels. One of them was future president Alfonso López Michelsen (1913-2007).

The children of the Colombian elite studied in Brussels. One of them was future president Alfonso López Michelsen (1913-2007).© Banco de la Republica

In the classrooms of Collège Saint-Michel, López Michelsen sat next to the European aristocracy. He found the atmosphere of the Jesuit college both oppressive and spartan but was much more enthusiastic about Leuven, the lively Flemish university town where he ended his stay in order to improve his French (!). In Leuven, he found the mentality more bohemian and Colombia seemed to be surprisingly close. ‘Three languages dominated in Leuven,’ he recorded in his memoirs, ‘Flemish, French and Spanish. Not the Spanish of Castile or Andalusia, with its typical lisping sounds, but the purest Spanish with a South American – I would almost say Colombian – accent.’

Collège Saint-Michel around 1912

Collège Saint-Michel around 1912© Wikimedia Commons

The quiet painter

The most famous and versatile Colombian in Brussels, the wise old man of the community, was also one of the most withdrawn during his lifetime. His public performances in Brussels were so limited in number, so devoid of fanfare, that it seemed as if he existed only as a shadow of a bygone era.

Self-portrait by Andrés de Santa María (1860-1945), 1910

Self-portrait by Andrés de Santa María (1860-1945), 1910© Wikimedia Commons

After many wanderings between Colombia and Europe, the painter Andrés de Santa María (born 1860) settled in Brussels shortly before the First World War – the same war that had, once again, temporarily dislocated him. He was recognised in his own country as a great talent and, in 1926, was given a commission by the president. In the beginning, Santa María was strongly influenced by Courbet and Millet, though his style evolved to become more impressionistic. It is primarily from his intimate portraits, often of family members, that an almost magical power emanates. Deeply absorbed in thought and gazing from a distance, as if some kind of protective spell that shields the canvas from the world has been cast, the people he portrays stare out at us. There is no tropical exuberance here, only a deep, European melancholy.

It was probably with some trepidation that Johan De Maegt, a journalist working for the Flemish daily newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws dared to visit the painter at the beginning of 1936, knocking at the door of a moody mansion in the Brussels municipality of Ixelles. The visitor was announced by a servant, whereupon a tall figure with a finely pointed moustache rose to shake the journalist’s hand. The Flemish visitor took in the surroundings, ‘and there [I was], in these rooms drenched in grey light, where old pewter work stood on the chimneys and, from the walls, luminous female heads loomed from mysteriously dark backgrounds.’ They went upstairs to the first floor, to the artist’s studio, complete with an easel. On the walls hung paintings that had never before been exhibited in public.

Andrés de Santa María: 'I wouldn't be surprised if the Brussels region arose from a corner of Eden, that earthly paradise.’

‘You work and yet do not show your work,’ said the journalist, perhaps reproachfully. ‘I hope to show it soon,’ the painter replied. ‘But the idea makes me shudder. Much of it originated within these silent walls, the work of a lifetime actually. To be a painter is tragic: your work leaves you, often never to never be seen again. You do not know what its future existence will be, you cannot change anything about it, it is always a final farewell.’

But the Colombian’s response to the next question was much more straight-forward.

‘You have travelled a great deal and have now been living in Brussels for twenty-four years. Does the atmosphere of the city benefit your work in some way?’

‘I have been to many capitals. Others are larger, but none has the charm of Brussels, which is so beneficial to the mind. Not one has all these parks, that forest, this wonderful location. I wouldn’t be surprised if the Brussels region arose from a corner of Eden, that earthly paradise.’ Santa María had not shown his work to the world for two decades. His home had become a sumptuous but sealed museum. Fame and prestige did not seem to interest him much. Life hadn’t always smiled at him – seven of his children had died – but the miracles were not used up.

The Flemish cultural icon, August Vermeylen, expressed his admiration for the Colombian painter

Was the interview a publicity stunt? Not two weeks later, the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels opened a retrospective exhibition dedicated to … Andrés de Santa María. Nearly one hundred canvasses – still lifes, portraits, and religiously-inspired works – were exhibited across five large galleries to display his skill. The public’s eyes were opened. ‘There has been a grey painter in whom a lasting fire burns,’ wrote the correspondent of the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf. ‘Too proud not to work in complete obscurity, too timid not to display a calm and natural modesty.’ The Flemish cultural icon, August Vermeylen, expressed his admiration for the Colombian. A year later, the Belgian art connoisseur André de Ridder devoted a study to the painter, and an even larger retrospective exhibition was held in London.

Almost as compensation for so many years of neglect, the Palace of Fine Arts then organised yet another retrospective exhibition at the end of 1941. By that time, Santa María himself was no longer in Brussels. He had moved with his wife to a village in the province of Namur, where he died in 1945.

The Belgian art connoisseur André de Ridder devoted a study to Andrés de Santa María.

The Belgian art connoisseur André de Ridder devoted a study to Andrés de Santa María.© 2dehands.be

Homesick for an unknown world

With Andrés de Santa María’s death came the end of an era. After the Second World War, the Colombians’ love of Brussels was no more than a distant memory. This farewell to Belgium could result in either nostalgia or outright bitterness. Darío Hernández, a pianist with round spectacles and pomaded hair, arrived in Brussels at the age of seventeen. He had taken a first prize at the Royal Conservatory of Music and was even summoned to perform for Queen Astrid. Having returned to the Colombian island of Santa Marta in the 1930s, he exposed his countrymen to Beethoven, Liszt and Chopin. But instead of drawing admiration, he was vilified for having forgotten the old familiar folk tunes. Hernández slammed the cover of his piano shut. This town was never going to hear him play another note! Until his death – and he lived to a ripe, bitter old age – he played with cotton wrapped around the piano strings. For several decades, not a single note emanated from his music room, only the clop, clop of his piano keys.

Some legends are too beautiful to check.

Historian and playwright Guillermo Henríquez Torres (1940-2021)

Historian and playwright Guillermo Henríquez Torres (1940-2021)© screenshot from YouTube

When it came to Brussels, Guillermo Henríquez Torres felt a kind of indefinable nostalgia and homesickness. I met the playwright in Ciénaga, a comatose city in Caribbean Colombia. Guillermo’s father had amassed a fortune from his banana plantation and, in 1926, he moved to Brussels, bringing his wife and nine children in his wake. The family moved into a mansion in Ixelles. At Casa Henríquez, with its salon full of Louis XV furniture, its marble staircase and crystal chandelier in the form of irises, the family received visitors from every part of South America, celebrities of the highest calibre, politicians and future presidents.

Perhaps little Álvaro Mutis had also visited once or twice. This poet and novelist, who died in 2013, was considered a literary great in the Spanish-speaking world. Mutis had spent his childhood in Brussels and though he had retained only a few tangible memories, his time there had an important influence on his work. He claimed that all the poetry he had ever written was focused on resurrecting his childhood. ‘It is sad poetry, full of homesickness, in which I try to reconstruct my life in Belgium and Colombia.’

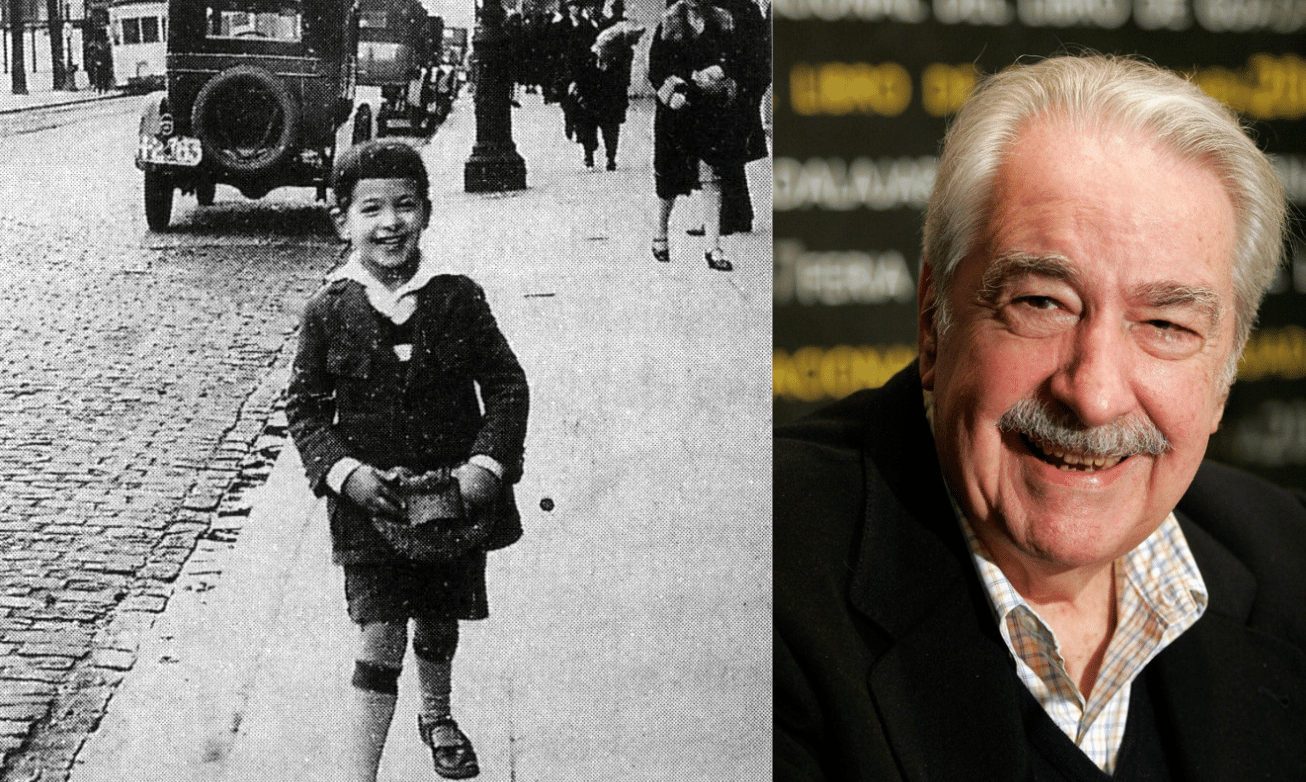

Poet and novelist Álvaro Mutis (1923-2013) has spent his childhood in Brussels.

Poet and novelist Álvaro Mutis (1923-2013) has spent his childhood in Brussels.I noticed a similar sentiment with Guillermo Henríquez Torres. For him, Brussels was a city in which he had never really lived, which he barely knew, and to which he felt too old to make a return visit. His home held an expansive collection of trinkets – he even had an early edition, almost falling apart, of One Hundred Years of Solitude with a personal, autographed note from the Master. Some of the relics were souvenirs of Belgium: one of his father’s colourful diplomas, (from the Dupuich Institute, academic year 1929-1930, a pass with great honours) and a series of pictures from the interbellum years ranging from portraits and class photos to images of family outings and fancy dress parties.

One of the photos shows a group of women in the typical fashions of the 1930s – classic, longer skirts in place of the coquettish fashions of the preceding decade. The central figure is a Colombian beauty queen who took part in the 1932 Miss World Pageant. The location of the photo? The Walloon city of Spa, where the pageant was held. The events of the Miss World Pageant have been captured on celluloid but I still cannot pick out Aura Gutiérez Villa among the demure candidates squatting in the front row of the photo. After the (Turkish) pageant winner was announced, the Pathé video shows festive reactions from the public. Perhaps members of the Colombian expat community were in the casino. Certainly present were the Dutch writers E. du Perron and Menno Ter Braak – it seems that even intellectuals enjoy a guilty pleasure now and then.

Each of Guillermo’s photographs evokes a surprising past. His Brussels paraphernalia reflects the Colombian’s longing for something he had really only experienced second-hand and, perhaps, idealised. The Colombians had left Brussels long before, but here, in a living room in a windless city under a leaden heat, this last breath of a vanished world was worthwhile.