When Did New York Stop Speaking Dutch?

The Dutch language persisted in some form in New York and northern New Jersey for nearly 300 years following the English conquest. While it declined in New York City in the early eighteenth century, it remained the primary language in many rural places until after the American Revolution. And although the language fell off substantially during the nineteenth century, a few isolated pockets of Dutch speakers survived into the twentieth century.

In the late summer of 1664, four English frigates arrived offshore New Amsterdam. Rather than resisting, the Director-General of New Netherland, Peter Stuyvesant, surrendered the city and colony to the English. Although the Dutch briefly regained control of the colony in 1673, it was restored to English rule in the Treaty of Westminster the following year, marking the end of Dutch New York.

Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch Director-General Of New Netherland, surrenders to the English in 1664, painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch Director-General Of New Netherland, surrenders to the English in 1664, painting by Jean Leon Gerome FerrisIn the immediate decades following the English conquest, the Dutch language predominated in what had been New Netherland. The Dutch generally resisted assimilation and retained their language. Anglicans in New York remarked in 1699 that the colony ‘seemed rather like a conquered Foreign Province held by the terrour of a Garrison than an English Colony.’ That same year, the New York colonial governor commented that the Dutch could ‘neither speak nor write proper English’. Among whites, the Dutch comprised the majority of New York City into the early eighteenth-century. In the Hudson Valley, the Dutch language remained even stronger. Immigrants to the region often learned to speak Dutch rather than English. Most of the French Huguenots who founded New Paltz in the 1670s adopted Dutch. Their church originally kept records in French, then switched to Dutch, and only later to English. Dutch cultural practices remained the norm as well. Roman-Dutch law prevailed, which allowed women to make joint wills with their husbands, wives to keep their maiden names, and for daughters to inherit land. Dutch legal practices endured until about 1730 in urban New York and lasted for a generation longer in rural areas.

Founded around 1683, the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow is the oldest church in New York State and among the oldest in the United States. It served as the inspiration for Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow".

Founded around 1683, the Old Dutch Church in Sleepy Hollow is the oldest church in New York State and among the oldest in the United States. It served as the inspiration for Washington Irving’s short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow".© Historic Hudson Valley

In New York City, the use of Dutch declined quicker than in the rest of the colony. The Dutch community in Manhattan was not as isolated as those in rural regions, and they were in frequent contact with English speakers. The arrival of new immigrants to the city, disproportionately from the British Isles, also undermined the use of Dutch. By 1730, whites of British descent outnumbered those of Dutch. In the first three decades of the eighteenth century, the Dutch were usually bilingual, using English in public and Dutch at home. After 1730, younger Dutch New Yorkers learned English and not Dutch, and by 1750, the language was generally only spoken among the elderly. The new generation tended to think of themselves as English. They also preferred English language religious services, and many left the Dutch Reformed Church for the Church of England. When Swedish botanist Peter Kalm visited New York City in 1749, he saw the decline of the language, and commented that most New Yorkers of Dutch descent were ‘succumbing to the English language’.

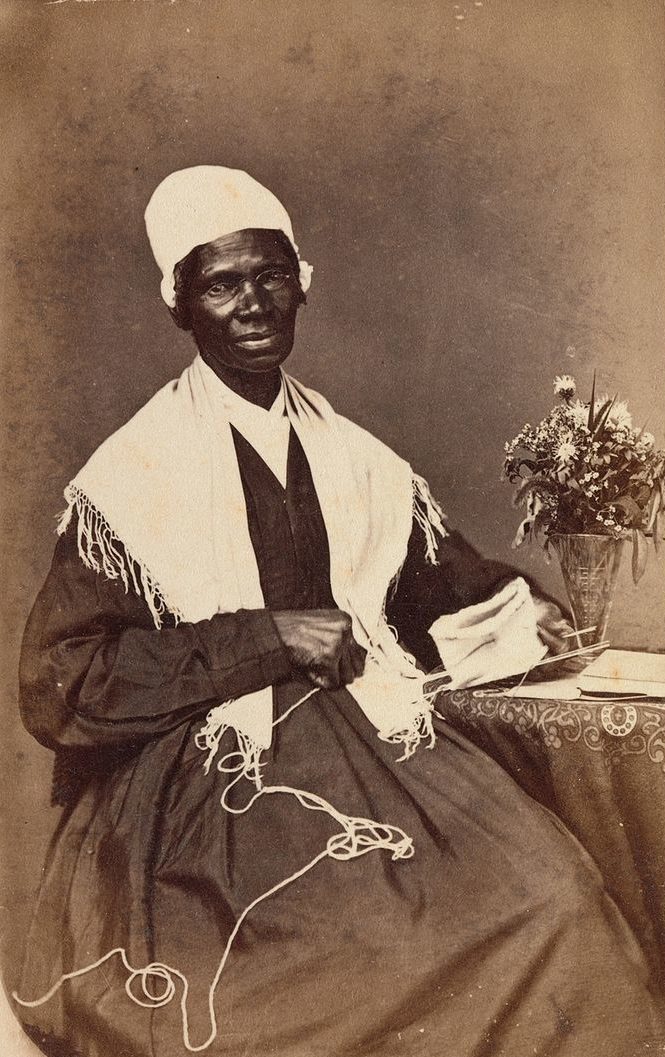

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883), who was born into slavery in Ulster County, grew up speaking Dutch as her first language.

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883), who was born into slavery in Ulster County, grew up speaking Dutch as her first language.© Wikipedia

In the Hudson Valley, the Dutch language remained strong until the late-eighteenth century. In many Albany, Dutchess, and Ulster county communities, Dutch was spoken more frequently than English at the time of the Revolution. Kingston kept its town records in Dutch until 1774. When Peter Kalm visited Albany in 1749, he said that ‘The inhabitants of Albany and its environs are almost all Dutchmen. They speak Dutch, have Dutch preachers, and the divine service is performed in that language.’ Richard Smith visited Dutchess County in 1769 and commented that ‘the Women and children could speak no other Language than Low Dutch.’ Another traveller, Patrick M’Robert, similarly noted in 1774 that in Albany the people were ‘mostly of Dutch extraction, whose language and manners they in a good measure retain, tho’ they can mostly speak English.’ In 1788, the new federal Constitution was translated into Dutch in Albany and published. The Dutch language was also common among black New Yorkers. Runaway slave advertisements frequently said that the enslaved spoke Dutch, and Sojourner Truth, who was born into slavery in Ulster County in 1797, grew up speaking Dutch as her first language.

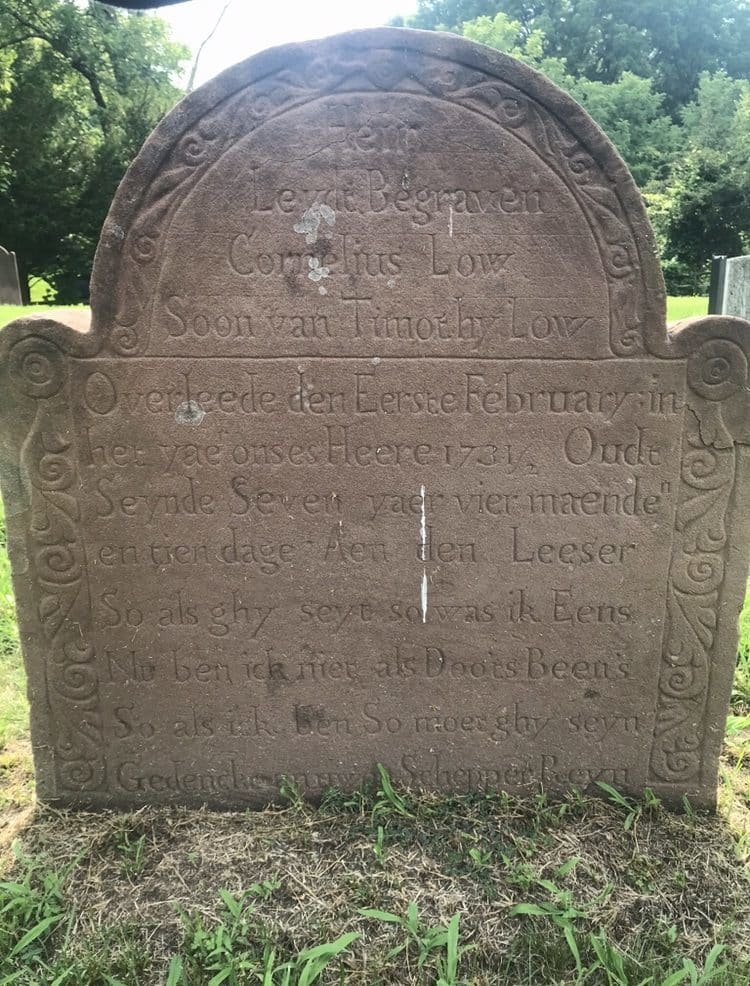

Headstone of Cornelius Low in the Old Hurley Burial Ground, Hurley, New York

Headstone of Cornelius Low in the Old Hurley Burial Ground, Hurley, New York© Kieran O'Keefe

Dutch began to decline more significantly in rural areas following the American Revolution. Some of these changes can be seen through churches. When the minister of the Dutch Reformed Church in Albany died in 1790, the church ceased to offer regular Dutch language services, to the dismay of some older congregants. Starting in 1808, records at the Dutch Church in Kingston were kept in English. The headstones in the cemetery of the Fishkill Dutch Reformed Church were generally engraved in Dutch before the Revolution but afterwards switched to English. At service, the Fishkill Church ceased using Dutch around 1800. The New Paltz Reformed Church conducted services solely in Dutch until after the Revolution when they alternated between Dutch and English to satisfy younger members of the congregation. Beginning in 1800, church records were kept in English and in 1817, English became the exclusive language of service.

Although not as widespread as during the eighteenth century, Dutch remained common in many areas of the Hudson Valley well into the 1800s. Reverend Gerardus Balthazar Bosch, a Dutch minister on the island of Curacao, noticed the prevalence of Dutch when visiting New York and New Jersey in 1826. He noted that the language was still spoken in Albany and Schenectady, although he found this dialect of Dutch ‘very bad, uncouth and coarse, and contaminated with many wrong expressions.’ In New Jersey, he heard Dutch in Hoboken and even met a farmer from Hackensack who did not speak English. Bosch again heard Dutch on several occasions in New York City, spoken by farmers from the Hudson Valley. In 1839, another observer said there were still residents in Dutchess County who ‘rarely speak any language but the low Dutch.’ Martin Van Buren, who was born in the old Dutch community of Kinderhook and was president from 1837 to 1841, spoke Dutch as did many others in the area.

House built by early Dutch Settler Luykas Van Alen in 1737 in Kinderhook, New York.

House built by early Dutch Settler Luykas Van Alen in 1737 in Kinderhook, New York.© Wikipedia

By the mid-1800s, the Dutch language had declined significantly, and its usage was disproportionately concentrated among the elderly. In 1842, The New York Herald reported

that Albany was ‘fast losing all its Dutch characteristics’ and that ‘the very language is forgotten’. In order ‘to hear it now in its purity a visit to the Helderburgh (a mountainous region in Albany County, ed.) is indispensable.’ In 1858, the same paper reported that the Dutch language among Lutherans was virtually gone except for a few congregations in New Jersey where some older congregants still spoke it. The following year, The Weekly Anglo-African commented that some elderly African Americans in Queens County could speak Dutch ‘as well as many Hollanders’ and that the black community was ‘strongly Dutch descent’.

By the mid-1800s, the Dutch language had declined significantly

Dutch was still spoken in old New Netherland in the late 1800s, but it was mostly confined to the Albany region and Bergen County, New Jersey. One Bergen County speaker of “Jersey Dutch”, born in 1860, said that when he grew up, ‘Jersey Dutch was the prevailing and natural form of speech in many homes of the older residents.’ In 1895, the New-York Daily Tribune reported

on the Dutch community in Hackensack, New Jersey. They noted that many of the descendants of the first Dutch farmers remained on the land and that some still spoke Dutch. In particular, the Tribune

said that the old women were ‘thoroughly Dutch’. The newspaper added, however, that the Dutch community would not last much longer, because many of the young people were moving away, and outsiders were settling in the community. In 1881, one man called on Dutch New Yorkers to support the South African Boers in their fight for independence from the British Empire. He asked, ‘Have they [Dutch New Yorkers] become so lost to sympathies with their race by contact with the English that they will not join in a movement to aid their kindred?’ He added that ‘even now in our farmhouses at Catskill, and in the counties of Albany, Rensselaer, and Duchess [sic], the descendants of the Dutch of New Netherland continue to speak the tongue of their forefathers in the sacred liturgy of home.’ A traveller passing through the Hudson Valley in 1909 found that the ‘Dutch language and customs still prevail to a surprising extent in the old villages up the Hudson.’

© Kieran O'Keefe

In the Albany area and northern New Jersey, the Dutch language survived into the twentieth century. Several linguists rushed to study the small communities of Dutch speakers, recognizing that the language would soon be extinct. In 1908, one scholar wrote ‘that there are also Dutch-speaking old colonists living upstream along the Hudson river in Albany and also in Schenectady County’ but that the younger generation did not know the language, meaning ‘it will soon have entirely disappeared.’ A study appeared on the Dutch spoken around Albany and in the Mohawk Valley in 1938. Another linguist visited Dutch speakers in Bergen County and published an article in 1910 detailing their dialect. Relying primarily on four individuals, all of whom were in their 70s or 80s, the article presented 664 words of Jersey Dutch. The author also said that Dutch was spoken by elderly African Americans on a mountain outside of Suffern, New York, but that they were hesitant to meet with outsiders and he had been unable to examine their language. Perhaps the last native speaker of Jersey Dutch, John C. Storms, died in 1949. His brother, who spoke the language to a lesser degree, passed away in 1962.

This article was first published on the New York History Blog.

Some selected sources for additional reading:

- Joyce Goodfriend, Before the Melting Pot: Society and Culture in Colonial New York City, 1664-1730 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

- Alice P. Kenney, Stubborn for Liberty: The Dutch in New York (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1975).

- Jan Noordegraaf, “A Language Lost: The Case of Leeg Duits (“Low Dutch”),” Academic Journal of Modern Philology 2, (2013): 91-108.

- A. G. Roeber, “‘The Origin of Whatever Is Not English among Us’: The Dutch-speaking and the German-speaking Peoples of Colonial British America,” in Strangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire, eds. Bernard Bailyn and Philip D. Morgan (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 229