When Farming Had to Become Big Business

Dozens injured and even one death: that’s how serious the mass farmers’ demonstration was against European policy reform in Brussels on 23 March 1971. This event not only marked the endpoint of a time when agriculture was still small-scale and mixed, it also signified the transition to production-oriented and technology-based agriculture. Fifty years later, farmers are once again facing huge challenges.

Fifty years ago, as many as a hundred thousand farmers from Belgium and the other member states of the European Economic Community (EEC) took over the streets of Brussels. On Tuesday, 23 March 1971, they demonstrated against the reform plans of the European Agricultural Commissioner Sicco Mansholt. The Dutch politician wanted to thoroughly and decisively tackle the structural problems facing the agricultural sector at the time. His ideas included higher prices, a decent income and better social conditions for farmers, but above all, the plans created unrest and were met with fierce resistance. The demonstration ended in chaos, and one participant even lost his life. As a result, the main principles of the reform were put on ice for a very long while.

On 23 March 1971, a hundred thousand farmers from Belgium and the other member states of the European Economic Community (EEC) took over the streets of Brussels.

On 23 March 1971, a hundred thousand farmers from Belgium and the other member states of the European Economic Community (EEC) took over the streets of Brussels.© Nationaal Archief / CC0

In 2021 another Dutchman – Vice-President of the European Commission Frans Timmermans – wants to make changes to the European Union’s agricultural policy. Together with the Green Deal, the Farm to Fork plan aspires to an agricultural and food system in which economy, health, animal welfare and ecology go hand in hand. Just like half a century ago, the agricultural sector is in full transition and the future looks uncertain for many farmers today. In this piece we not only give a bird’s eye view of how agriculture and food policy has evolved in Belgium and the Netherlands in recent decades, but we also examine what can be learned from the great farmers’ demonstration of 1971. What legacy has it left behind? And what similarities and differences are there between then and now?

Never go hungry again

In many ways, the roots of European agricultural policy can be traced back to the Second World War. After several years of food scarcity and famine, national governments wanted to become self-sufficient. Driven by the motto ‘never go hungry again’, and by means of modernisation, scaling-up, extensive mechanisation and motorisation, agriculture experienced a spectacular growth spurt. Pre-war production levels were equalled as early as 1950, and exports of food and agricultural products flourished again. In the Netherlands, this happened faster and with more force than in Belgium, but the overall trends were very similar. For example, the old mixed farming model, which combined arable and livestock farming, evolved into more specialised agriculture and horticulture that increasingly relied on products from outside the individual business. For example – animal feeds, seeds, fertilisers and chemical pesticides.

Modern machines quickly replaced human and animal labour. While there were about 8,000 tractors in Belgium in 1950, this number had grown to over 90,000 twenty years later. The effect on returns was considerable. It made it possible to produce (remarkably) more with (far) fewer farmers. In 1950 there were 256,754 companies active in the agricultural sector in Belgium (82 percent of which were smaller than 10 hectares), by 1970 this number had fallen to 184,000 companies. Employment in the primary sector also fell dramatically in the Netherlands: from 718,000 farmers and workers in 1947, to 340,000 in 1970. Especially the small scale farmers left the agriculture sector, which enabled those remaining to expand their operations. Between 1950 and 1970, the average farm size in Belgium rose from 6.8 to 11.7 hectares, and in the Netherlands, it grew from 10.2 to 15.3 hectares.

By means of modernisation, scaling-up, extensive mechanisation and motorisation, agriculture experienced a spectacular growth spurt after the Second World War.

By means of modernisation, scaling-up, extensive mechanisation and motorisation, agriculture experienced a spectacular growth spurt after the Second World War.© Nationaal Archief / CC0

The developments described above were part of a broader transformation that radically changed the food system. The agricultural sector was becoming increasingly capital intensive, experiencing the ever growing power of agribusiness and retail. And above all – after the Second World War, Belgian and Dutch farmers were operating in an increasingly internationally oriented food system.

The first attempts to cooperate structurally across borders, were however fraught with difficulty. In 1948 the customs union between Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg was launched (through the Netherlands–Belgium–Luxembourg Customs Convention), but due to pressure from farmers in Belgium and Luxembourg, the import of the highly competitive Dutch dairy and horticultural products was subject to strict conditions.

In 1957 the Treaty of Rome followed, in which six European countries united (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, West Germany and Italy). Among other things, the basic principles of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) were to ensure sufficient and affordable food for consumers, stable prices, and viable farms with reasonable incomes for farmers. The CAP took shape for the first time in 1962. Core elements included a common internal market, a common dairy scheme and a common grain price. Partly due to the relatively high price guarantees for these agricultural products, as well as modern farming technology, farmers chose to increase their production, which quickly and infamously resulted in butter mountains, and milk and wine lakes. Getting rid of these surpluses cost the EEC a great deal of money and met ever-increasing criticism. But how to tackle this problem? The architect of the CAP had a solution.

“Good Things and Reprehensible Things"

In late December 1968, Sicco Mansholt launched the Mansholt Plan – its full and official title the Memorandum on the Reform of Agriculture in the European Economic Community and Annexes. The huge, six-part document proposed measures to restore European market equilibrium, tackle overproduction and end income inequality between farmers and workers and self-employed workers from other sectors. Mansholt wanted to make farming more modern and liveable, and for example, believed that farmers were entitled to holiday like everyone else. To achieve that, farms had to become bigger and more profitable. Mansholt proposed price measures and a reduction of the agricultural area by 5 million hectares (6 percent of the total cultivated area). The active agricultural population had to decrease by 5 million farmers (45 percent of the total). Stimulated by retirement benefits and scholarships, farmers could re-skill and retrain professionally. Larger business units needed to replace smallholdings. Mansholt had concrete numbers in mind: the size of the modern arable farm needed to be 80 to 120 hectares. Dairy farms ideally needed between 40 and 60 cows, and for pig farming, the standard was 450 to 600 livestock.

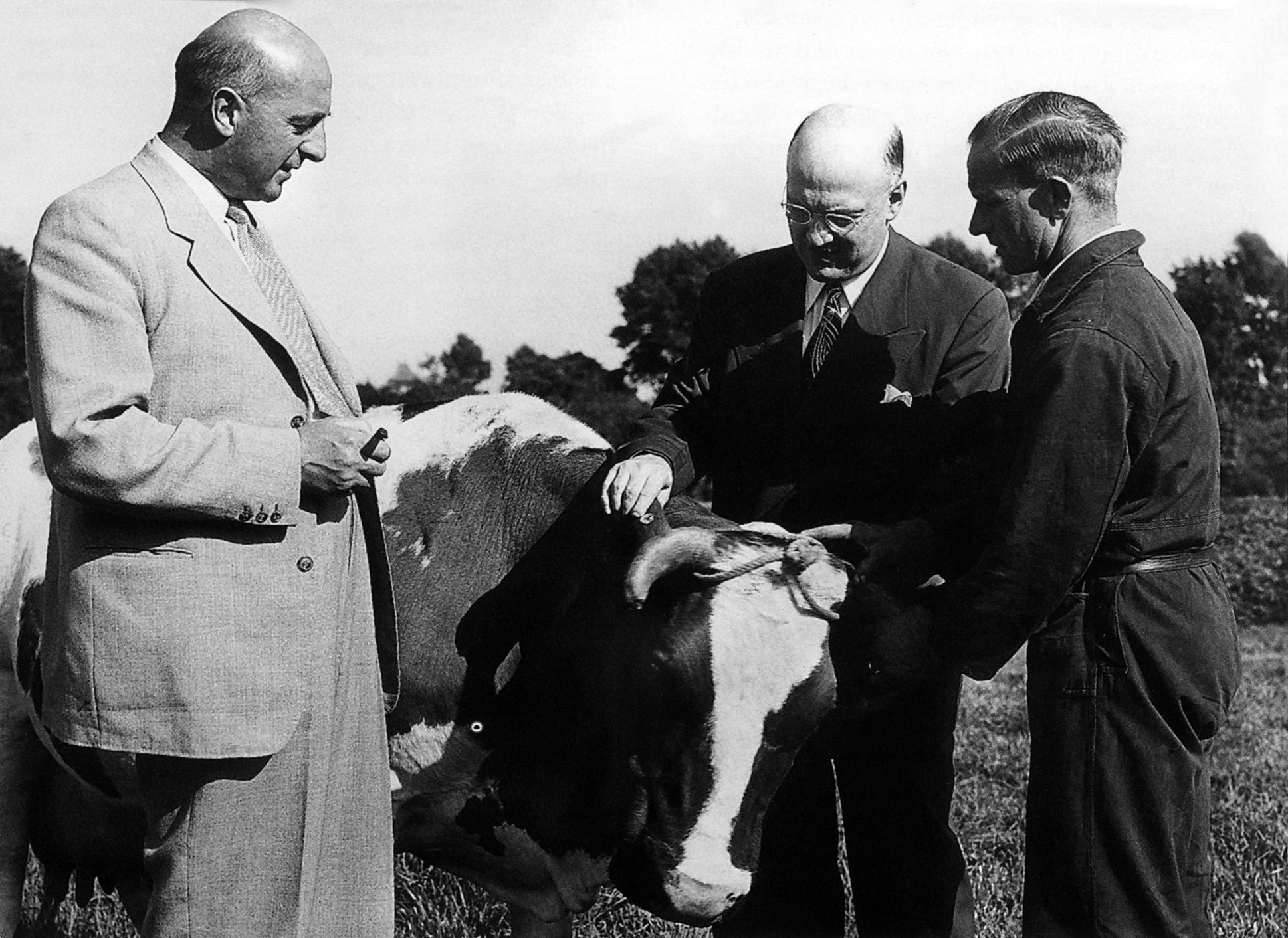

Sicco Mansholt (left) as Dutch Minister of Agriculture in July 1951

Sicco Mansholt (left) as Dutch Minister of Agriculture in July 1951© From the book 'Mansholt. A biography of Johan Van Merriënboer' (Boom, 2006)

‘There are good things, and there are reprehensible things in the Memorandum’, Constant Boon, the then chairman of the Belgian Farmers’ Union, concluded in a speech in February 1969. That statement summed up the initial reactions to the Mansholt Plan well. Practically everyone was convinced that drastic reform was needed, but the price proposals and especially the structural reforms received very little approval. The very rapid and radical change that Mansholt was asking for was seen as threatening and unrealistic. Farmers’ representatives in the Low Countries portrayed Mansholt – a member of the Social Democratic PVDA – as a Marxist. The “mammoth businesses” he was proposing reminded them of Soviet Kolkhozes.

Farmers felt that the fruits of the golden sixties were passing them by

Doubts soon arose as to whether Mansholt and the European Commission would be able to find a ready-made solution for the multitude of agricultural problems that this Europe of the Inner Six faced. After all, every country had its own agricultural structure. Their focus on export varied, they all excelled in producing certain crops… It was not easy to get everyone on the same page. In the Netherlands, for example, there was a great fear that too much would have to be paid to aid the lagging regions in southern Europe, and Belgium turned out to be a great defender of the family-run business. All governments, however, feared the reaction of small farmers. With so many, their political weight was not insignificant. But how could they be included in an adapted agricultural policy? Was it at all necessary to do so? The Netherlands, for example, were less sentimental about family-run businesses. The desire to develop rational economic agriculture, ready to conquer the export markets, was strongly present in the government and the Chamber of Agriculture, which promoted the common interests of farmers’ organisations.

This laborious search for compromise among politicians systematically increased anxiety amongst farmers. Stagnating agricultural prices and the indisposition of the European Council of Ministers cultivated a desire to take action. Unlike many of their fellow villagers, labourers and service workers, farmers felt that the fruits of the golden sixties were passing them by.

Call to action

By the beginning of 1971, enough was enough. In the past protests had been organised separately by different national agricultural organisations, but now they joined forces. The European umbrella organisation COPA (Committee of Professional Agricultural Organisations) called for a joint protest to take place in the European capital, with people from across ‘the entire agricultural sector’. In Belgium, the Boerenbond (Farmers’ League), the Alliance Agricole Belge (Belgian Agricultural Alliance) and the Fédération des Unions Professionnelles Agricoles (Federation of Professional Agricultural Unions) – the three largest and most established agricultural organisations – united for the first time as the so-called Green Front. The Algemeen Boerensyndicaat (General Farmers’ Syndicate), which was founded in 1961 and was more protest-oriented, also put its weight behind the demonstration. Their position: ‘Prices first, then the rest.’

The run-up to the 23 March demonstration was pretty vigorous. In several European (capital) cities, farmers took to the streets to express their grievances. On 15 February, it became clear that a serious confrontation was imminent. A number of Walloon farmers even managed to get into a session of the Council of Ministers with three cows. The following weeks saw strike actions, and parades with tractors and roadblocks in many provinces in Belgium and the Netherlands. These smaller protests were to act as a “warm-up” for farmers, ahead of the big demonstration, and were simultaneously a measure of their willingness to take real action. That willingness was clearly enormous. The agricultural organisations mobilised en masse and did not shy away from inflammatory language. A call to action was circulating in Flanders, and it including the following warning: ‘Anyone who does not march on 23 March, no longer deserves to be called a farmer.’

In the run-up to the big demonstration in Brussels, things were already unsettled: Belgian farmers demonstrated in the Netherlands, for example.

In the run-up to the big demonstration in Brussels, things were already unsettled: Belgian farmers demonstrated in the Netherlands, for example.© Nationaal Archief / CC0

The success of this call to action also laid the groundwork for the chaos that would break out on the day of the demonstration. The starting point of the march lacked sufficient parking spaces for the numerous buses. Many farmers had come to Brussels early and went for a drink whilst they waited for the demonstration to begin. As the crowd grew ever larger, the organisers and the gendarmerie decided to let the demonstration leave earlier. Without speeches taking place. The demands on the banners and placards left little to the imagination, for example: ‘Hitler murdered the Jews, Mansholt the farmers.’ As the day wore on tension increased on the streets of Brussels. Demonstrators shouted all kinds of slogans. Firecrackers exploded, rotten tomatoes were thrown, but it didn’t stop there. When a few demonstrators (who according to the organisers were infiltrators not farmers) destroyed traffic lights and smashed windows, the gendarmerie intervened. The chaos was complete and street fighting broke out. The gendarmerie responded with tear gas and a young Walloon farmer was accidentally killed.

Demonstrating farmers with a puppet on the gallows and a sign 'Our fate'. 'Hitler killed the Jews, Mansholt killed the farmers', was another slogan during the demonstration.

Demonstrating farmers with a puppet on the gallows and a sign 'Our fate'. 'Hitler killed the Jews, Mansholt killed the farmers', was another slogan during the demonstration.© Nationaal Archief / CC0

The riots and huge damage left a deep impression on the protesters, many of whom had come to the capital for the first time. There were mixed reactions from agricultural organisations. On the one hand, there were feelings of horror and shame because the demonstration spun so out of control. The mainstream press also focused mainly on the chaos and violence, although there was also some understanding of the farmers’ anger. The agricultural media obviously sided with the farmers. At the same time, the farmers’ organisations were proud of such a high turnout to the protest. They saw this as a very clear signal to Mansholt and the other politicians that urgent decisions had to be taken. Drietandmagazine, the General Farmers’ Syndicate magazine, wrote: ‘We cannot escape the feeling that the demonstration on 23 March has opened up a new chapter in the history of Belgian farming. (…) 23 March has perhaps made it clear to even the most stubborn-minded, that people can’t play with farmers’ lives without there being consequences.’

© Nationaal Archief / CC0

A steady change in direction

The 1971 Farmers’ Demonstration was thus not only the symbolic endpoint of a time when agriculture was still predominantly small-scale and mixed, with farmers forming the core of rural communities. It can also be seen as the start of a new European approach, as well as a transition to fully production-oriented and technology-based agriculture. Fifty years later, the “mammoth farms” that Mansholt had envisioned, are now actually small family-run businesses, and his “mega stables” are still the subject of discussion. The active farming population has also fallen sharply: in 2019 Belgium still had about 36,000 farms, and in the Netherlands, that was around 53,000.

The demonstration in Brussels was the first transnational farmers’ demonstration since the Common Agricultural Policy came into being. And it certainly wasn’t the last. It was clear to all that Europe was shaping agricultural policy, not national governments. Moreover, the unanimous and intense reaction against Mansholt’s reform plans had a direct impact. The entire plan was scaled back and was predominantly made up of support measures for the modernisation of farms, a government-funded redundancy scheme for farmers, and some measures for personal education and development. Additionally, the Council of Ministers had already decided to increase prices for some agricultural products, including milk.

The farmers’ organisations had shown their teeth. In the decades that followed, the agricultural policy would only be adjusted very slowly. Politicians feared the power of the farming organisations, who also understood the art of lobbying well and often put the brakes on when reforms were discussed.

In the decades that followed, the agricultural policy would only be adjusted very slowly

For a long time it was overproduction in certain areas that determined the agricultural agenda, and only very slowly did policymakers put things like animal welfare, the environment and climate on the agenda. For example, it was not until 1984 that measures were taken to restore market equilibrium, for example through the introduction of milk quotas. Action was needed, because no less than 30% of the European agricultural budget was used on price interventions in the dairy sector. From then on, the tone was set. The farmer was not allowed to produce more than was stipulated in advance. Europe wanted to reconcile supply and demand. Farmers who produced more than agreed were fined.

Another step was taken in 1992 under Agriculture Commissioner Ray MacSharry. A farm’s income and its level of production were separated step by step. It wasn’t just the level of production that mattered, but also the way in which it was realised. Direct income support for farmers and support for more extensive and environmentally friendly farming were the new instruments. In short, from the 1990s onwards, European agricultural policy had more of an eye for quality, and after the turn of the century, farmers had to pay more attention to environmental regulations, animal welfare and food safety. Like a large ocean liner, the policy changed course only slowly. Too slow and too insufficient for some, but far too drastic for others. And within a union of 27 member states that change is even more difficult than in 1971.

From Farm to Fork

With the Green Deal and the Farm to Fork plan, there are new plans currently on the table. There are some curious parallels to be seen between Sicco Mansholt at the time and Frans Timmermans today. Both want to take the agricultural sector in a new direction. But just like half a century ago, farmers now fear – and not without reason – a significant loss of income and the closure of many farms. Is it a coincidence that Mansholt and Timmermans are both Social Democrats? They undoubtedly have more freedom of movement than Christian Democrats, who traditionally align themselves closer to the farming sector.

Mansholt hoped to be able to realise a better income for farmers with his 1980 plan. This required farms to adjust structurally to form larger, more profitable business units, which in turn would be coupled with a more efficient European pricing policy. The clear and quantifiable objectives of the plan, such as cutting the farming population in half, provoked strong resistance.

There are some curious parallels to be seen between Sicco Mansholt at the time and Frans Timmermans today

Today’s Farm to Fork strategy puts forward rather general objectives – which seems more strategically sensible. It is committed to high-quality, sustainable agriculture that it is hoped will automatically strengthen the competition and market position of farmers – and that the domestic and foreign market will reward these products with a fair price.

Policymakers today also have to take more stakeholders into account than they did half a century ago. Agricultural policy has become part of a global food policy, a policy that aims to improve biodiversity, tackle climate challenges and nurture rural heritage… As a result, it ensures that farming and food production in the twenty-first century are not exclusively the concern of farmers, but are also concern citizens and consumers. Rolling out sustainable and future-oriented agriculture and food policy is a more difficult task than ever before. And even fifty years down the line, the main stumbling block is still guaranteeing European farmers and market gardeners a decent income.