‘When It Comes to Language, I’m a Sentimentalist’

In the series Babel in the Low Countries, editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere contemplates the way we use language today, but just as easily delves into the past to consult with historical figures and writers who stand guard over language. In this article he tells why he considers himself a language romanticist.

Language is similar to what time is for Augustine: you know what it is as long as no-one asks. Yet, as soon as someone asks you to explain what language actually is, it causes immense embarrassment. We are all experts and all equally ignorant when it comes to language. The reason being that language is all around us. It is not just the philosopher who gets caught up in the nets of language, as Nietzsche once claimed: we are all caught up in that same net.

We are all caught up in the nets of language

Language is mundane; possibly the most ordinary and yet, at the same time, the most peculiar thing to ever happen to us. None of us possesses language, and none of us masters it completely. When I die, language, the languages I lived in, will survive me. You could compare our lifelong attempt to control language to setting up camp near a glacier on the way to a top of a mountain we will never reach.

We can say there are, broadly, two positions on language. The first one considers language an instrument, a means to express what we think. Language is a gown we use to dress things up in, a vehicle for our thoughts. In this view, things and thoughts are already out there, even before we say them. We attempt to construct an unambiguous relationship between thinking and speaking, between reality and language. Language is used to adequately represent, reflect that reality.

I am a regressive language sentimentalist

There is another position – a more ‘romantic’ one – that believes we express our inner through language. Through language, through speaking, we become who we truly are, we become ourselves, we say “I”. By stammering and by, eventually, speaking, we give meaning and substance, we order reality, we create the world. ‘Wir können nur eine Welt begreifen die wir selber gemacht haben.’ I would paraphrase this quote by Nietzsche as follows: we can only understand the world if we speak it. According to this view, there is no such thing as an unambiguous relationship between language and reality.

You could in fact link these two takes on language to the question whether language determines thought, or the other way around, thought determines language. It is my belief that language might not determine our thoughts, the way we perceive reality, but it definitely affects it. When I am speaking French, I am not quite the same person I am when I am speaking Dutch. Clearly, I am more of a romanticist than I am an instrumentalist when it comes to language. A romanticist will consider language as important and substantial: language is thus be the spine of one’s identity, both for individuals, and groups and communities. In any case, those romanticists do not deem language a currency or a medium of exchange. Their opponents would call them “language sentimentalists”, and will often add the epitheton ornans “regressive”. Well, then: I am a regressive language sentimentalist.

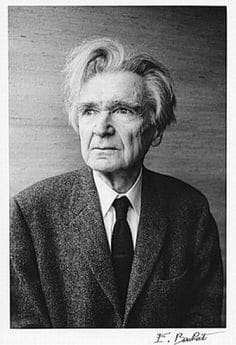

Emil Cioran (1911-1995)

Emil Cioran (1911-1995)Take, for instance, Romanian author and philosopher Emil Cioran. He arrived in Paris in 1937 with a scholarship from the Institut Français in Bucharest. He never moved back. In 1949, he published his first book in French, entitled Précis de décomposition. He rewrote it no fewer than four times, and never hid the fact he found French quite challenging. Similar to his predecessors Nabokov and Conrad, and Kundera would do later on, Cioran traded his mother tongue for another language. He spoke many wise words concerning that exchange.

According to him, he who denies his language, changes his identity, commits heroic high treason. To a writer that is equal to drawing up a love letter with the help of a dictionary. Remarkably, he once confessed that a genuine writer locks himself inside his mother tongue: he limits himself out of self-defence, for nothing is more detrimental to talent than too much open-mindedness. And to cap it all, Cioran claims that a people is fully decadent, as soon as it stops believing in its own language. If a people stops thinking that its language is the highest form of expression, language itself.