The Dutch portrait photographer Hendrik Kerstens struggles to choose amongst the many Old Masters that inspire him. Ultimately, he decides upon Jan van Eyck’s (ca. 1390-1441) Man in Red Turban (Man met de rode tulband, c. 1433) and the Portrait of Haesje Jacobsdr. van Cleyburg (1634) painted by Rembrandt (1606-1669). Both masterpieces have helped him blur the line between the painter’s art and photography.

In my photographs, I try to absorb and then renew various artistic traditions. I want to avoid mimicry, because for me, it is about recreating and reinterpreting visual cultures. That’s why I try to contextualise and understand texts about and images by the Old Masters.

The difference between painting and photography

Jan van Eyck’s painting Man in Red Turban startles me because it breaks so resolutely with previous portrait traditions. According to several art historians, this masterpiece is considered as the first modern portrait in Western Art History. Furthermore, the man’s pose has become the prototype for face-on and side-on portraits and that is the main thing: the man looks the viewer right in the eye. This is where the history of the pictorial exchange between the human gaze and the viewer originates,1 so anyone who creates similar portraits is in a sense indebted to this masterpiece.

Jan van Eyck, Man in Red Turban, 1433, National Gallery, London

Jan van Eyck, Man in Red Turban, 1433, National Gallery, London© National Portrait Gallery

Van Eyck set out to confront the audience with this portrait and the eye contact forces a reaction. There really aren’t any details that distract from it, although the red turban remains the pars pro toto of the painting. It is just about possible to distil paintings by Mark Rothko from the folds of the turban. In its very simplicity, this portrait is immensely complex, and the effect of its depth is almost abstract.

The combination of pictorial and abstract effects in this painting creates a constant tension between elements of truth and the artist’s personal idiom. After I had studied the turban extensively for my own portrait Red Turban (2015), I discovered that such a headdress could not actually be folded in any realistic way.

Hendrik Kerstens, Red Turban, 2015

Hendrik Kerstens, Red Turban, 2015© Hendrik Kerstens

That is when I stumbled across the first clear difference between painting and photography: ideas in the mind of the artist can be freely expressed in painting, but not in photography. Put more simply: because the mechanical shot of a camera defines an imprint of reality, a photo is essentially a testament to something that was once real. Fortunately, digital editing programs allow a photographer to compete, to some extent, with the free forms of expression that are possible in painting. By using some of those tools I can explore the possibilities that photography has to offer. With them, I try to convert different dimensions of reality and unreality into a tangible result and am able to capture my passion for painting and my fascination for still life portraits in my own body of work.

Ideas in the mind of the artist can be freely expressed in painting, but not in photography

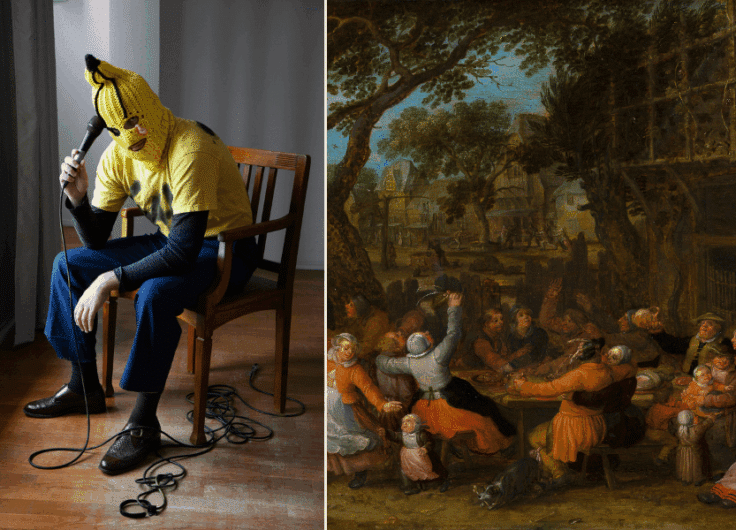

Through my attempts at fathoming and processing visual traditions, I also want to bring classic forms and techniques into dialogue with a contemporary visual language. That’s why I use objects from my daily surroundings. I have to be able to change everyday, throw-away objects such as plastic bags, aluminium foil, serviettes or loo roll into portable attributes via simple interventions, thereby giving them the ability to resonate with the collective memory.

In this way I can highlight the beauty of insignificant materials and make a conceptual leap in time to the descriptive character of our history of art. Because what really fascinates me about Northern European art is the way in which paintings can be interpreted as descriptions of daily life.

Eliminating the barrier between the virtual world and reality

When I look at the Portrait of Haesje Jacobsdr. van Cleyburg by Rembrandt, I see more than just an objective reproduction of reality. The painting feels like a tangible statement of the relationship between the artist and his female model. It’s as if the composition has been constructed out of many recorded moments and the emotions of the woman are trapped in the painting.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Haesje Jacobsdr. Van Cleyburg, 1634, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt van Rijn, Portrait of Haesje Jacobsdr. Van Cleyburg, 1634, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam© Rijksmuseum

The beauty of the portrait, therefore, is not really due to the practical act of painting itself but, rather, from the way in which the psyche of the model is depicted. The portrait is inviting because of the subject’s nascent smile. At the same time, her serenity and radicality shine through. And despite the distant nature of the distinguished lady, Rembrandt was able to create a sense of intimacy. This is why he is the primus inter pares when it comes to eliminating the barrier between the virtual and the real.

That is also something that I strive for. It is my goal to always add a dimension to my photographs whereby the person being portrayed conveys the feeling that the camera is not present. Incidentally, Rembrandt taught me that the signature style of an artist is created by the skilful use of the medium combined with a sublime eye for the contrast between of light and darkness.

After my interest in the Flemish-Dutch school, my knowledge of cameras and graphic techniques has a deciding influence on the methods I apply.

Hendrik Kerstens, Bag, 2007

Hendrik Kerstens, Bag, 2007© Hendrik Kerstens

The sobriety, the clarity, the highlights and serenity in my photographs determine the final decision. But the details, and the manner of observing them, also play their part in the expressiveness of my compositions. On a more emotional level, I try to address the reality of the waste of disposables, while simultaneously stressing my love for my daughter (a regular model). My contemporary subjects allow me the opportunity of freedom in the artworks I create. I will not accept the hindrance created by established motifs or the boundaries of the photographic medium. I believe in a fusion between photography and painting because the pictorial effect in both disciplines can be practically the same.

This article is written in collaboration with Paula Kerstens.