On 2 September 1920, the Red Devils won their first and only trophy. During the Olympic football finals in Antwerp, the Belgian team beat Czechoslovakia 2-0. That win meant Belgium won both the title of Olympic ànd World Football Champion, ten years before the actual world championships were first organised. The Red Devils’ core at the time was made up of Front Wanderers, footballers serving in the military, who played matches during World War I in aid of Belgian refugees and frontline soldiers.

The match was characterised by two peculiar events. First of all, over 40,000 spectators watched the game, even though the stadium could only seat 25,000 people. About 15,000 football fans snuck underneath the fences through holes they had dug the night before. The second peculiarity was that the Czechoslovakians left the pitch after 43 minutes, and never returned. They did so in protest against the referee’s decisions, which they termed ‘mistakes’. Belgium is the only country in the world to ever win an important trophy that way.

Over 40,000 spectators watched the football final between Belgium and Czechoslovakia.

Over 40,000 spectators watched the football final between Belgium and Czechoslovakia.There is yet another extremely curious tale linked to the Olympic football finals. The Belgian team’s trailblazer was Armand Swartenbroeks, who played for national champion club Daring Bruxelles Football Club, studied medicine at the Université Libre de Bruxelles and was a known humanist. When World War I broke out, he took the train from Brussels to the frontlines around Ypres. The novice doctor saved the lives of thousands of soldiers and assisted many dying ones. Armand co-founded the ‘Front Wanderers’, a squad consisting of international players that would play benefit matches in the United Kingdom in aid of Belgian war refugees and frontline soldiers fighting in the trenches. Three years later, the Red Devils, with the Front Wanderers at their core, were crowned the Olympic champions.

Flag of the Front Wanderers

Flag of the Front WanderersSwartenbroeks’ brother

2 September 1920. Armand Swartenbroeks was thinking about his brother. There he was, holding the cup. He looked out at the elated crowds, over 40,000 spectators. He was now an Olympic champion, after beating the brand-new nation of Czechoslovakia, which was technically the world’s number one team. And, boy, had those Czechoslovakians been a tough nut to crack! In the summer of 1919, they had won the ‘Inter-Allied Games’ in Paris, which were the Olympic Games for military personnel who served in the allied armed forces. They had beaten Belgium 4-1 in the semi-finals. Therefore, they had been the true number one.

That is, until this very moment. Now, it was the Red Devils’ turn. His Red Devils and their achievements had been quite the sight to behold. In May 1919, they had won the Kentish Challenge Cup, the first military triangular tournament between the British, French and Belgian armies. Three weeks after that, Bohemia and Italy were defeated in another football event. And at the Inter-Allied Games, they took the bronze after beating Canada and the United States. And once again he felt the vibrations, the Olympic gold medal! But still…

The Red Devils at the Olympic football final in Antwerp, 1920

The Red Devils at the Olympic football final in Antwerp, 1920Armand Swartenbroeks’ thoughts turned to his brother. His deceased younger brother Alexis. He was killed in battle on the frontlines in 1915. Those miserable frontlines of that wretched Great War. Armand was forced to bring his studies for a medical degree to a halt in the winter of 1914 and decided to volunteer as a medical student on the frontline behind the Yser River. His younger brother Alexis was also conscripted into the army.

Both Armand and Alexis were members of ‘den Deiring’, the red and black Daring Bruxelles Football Club, whose home base was on the border between Koekelberg and Molenbeek. Back then, the club was the most important representative of Belgian football, having won championship titles in 1912 and 1914, and having come in second after a tiebreaker for the title in 1913.

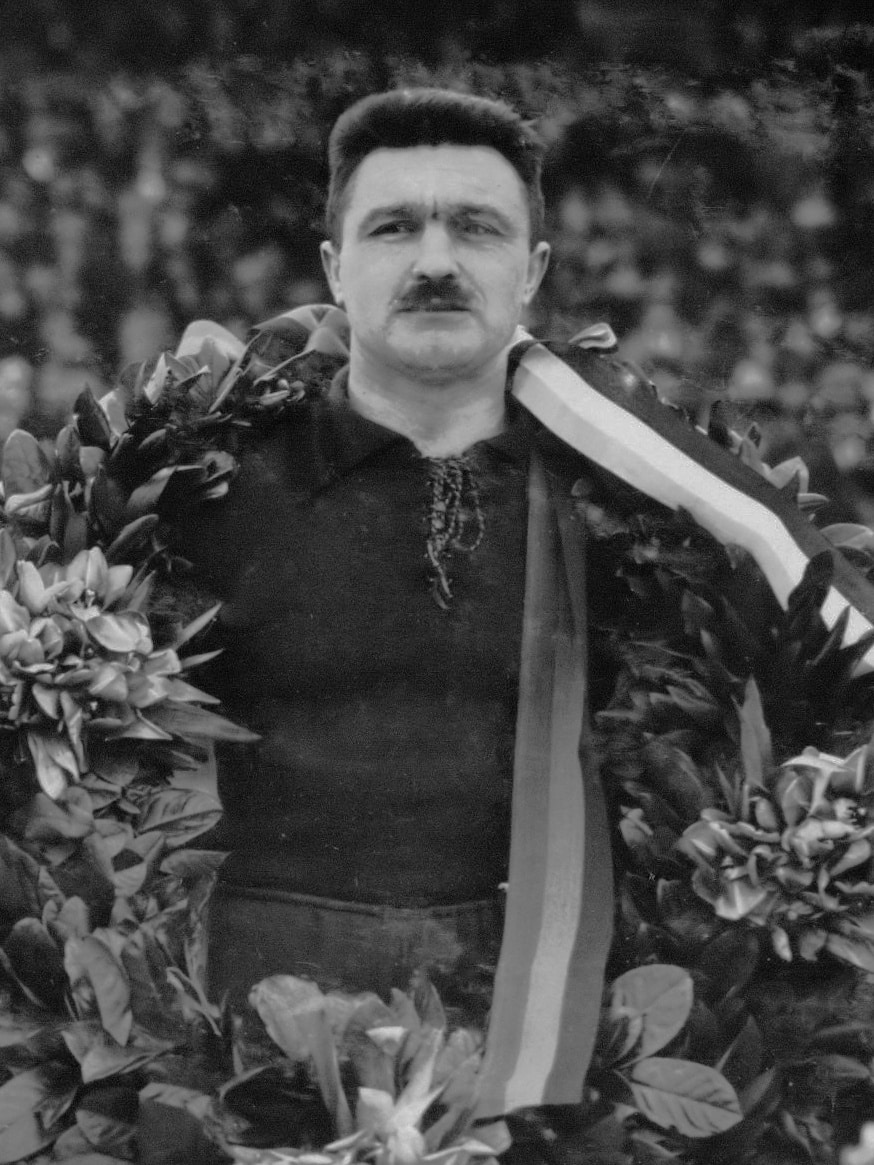

Armand Swartenbroeks

Armand SwartenbroeksThe assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria on 28 July 1914 abruptly ended the rise of the talented Daring generation. Despite a month of complicated threats and coercive diplomacy, World War I definitively broke out at the beginning of August. During Kaiser Wilhelm’s tyrannical reign, Belgian was overrun by the German troops. The capture of Westhoek in October 1914 meant that the last patch of Belgium was within reach. However, The German advance was stopped because the Belgian commanders in chief had decided to flood the Yser valley. A devastating four-year period of trench warfare in the area between Nieuwpoort and De Panne was imminent.

Combat and care at the Yser Front

A number of Daring players received an official letter imposing conscription, among whom were the Swartenbroeks brothers. Armand remembers taking the train in the capital to Westhoek and looking out at the war-ravaged land, on his way to fight for king and country in that final stretch of unoccupied Belgian territory. But most of all, to ‘care’ for king and country.

Being an aspiring doctor, Armand experienced the true madness of war first-hand. Thousands of young men his own age died in his arms. He would also perform painful medical procedures, including the treatment of ‘trench foot’. Great sorrow clouded his eyes as he looked upon the horrors of life between the corpses in the trenches for this lost generation of men between the ages of sixteen and thirty: a rat-infested, muddy ditch filled with filthy water. Death was his daily travelling companion. More often than not, its presence meant a liberation from suffering. We are the Dead. Short days ago. We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie in Flanders Fields.

Main entrance of the Olympic Stadium in Antwerp, 1920

Main entrance of the Olympic Stadium in Antwerp, 1920Armand survived that four-year-long killing spree in Flemish Fields. His brother Alexis did not. Armand had been forced to leave him behind. In Flanders Fields. He thought about him. He thought about him every single day. Even in that moment of ultimate athletic victory, when he was allowed to hold that golden Olympic cup. But still, his sadness was interspersed with moments of pure joy. After all, he had managed to bring the cup home with his Front Wanderers.

In the weeks following the German invasion in the summer of 1914, about one and a half million Belgians fled to the Netherlands, France and the United Kingdom. The Belgian refugees were particularly well-received in England and Scotland. War refugee committees were founded to show solidarity with ‘Poor Little Belgium’, and the entire Commonwealth realm, including countries as remote as Canada and Australia, offered financial support. Armand found the British gesture to be admirable, but the senseless massacre between the Yser River and the Somme seemed never-ending. The price the European continent was forced to pay was too big to even comprehend.

Football for peace, refugees and country

Fortunately, nothing could ever crush the desire to play ball. Armand had been extremely excited about the Front Wanderers project: an unofficial national squad consisting of footballers serving in the military, who played benefit matches in aid of Belgian war refugees. He perceived it as a project that would divert attention away from the misery of war and could ease the pain. It fit in with his outlook on life. He was a proponent of humanism. And he connected that philosophy to the medical aid he offered the victims of violence, but also to ‘playing football for a good cause’. For peace, for the refugees as well as for the nation.

The Front Wanderers played against the British army team in the stadium of Manchester United in 1917.

The Front Wanderers played against the British army team in the stadium of Manchester United in 1917.The Front Wanderers considered him their spiritual leader and their destination. He liked the sound of that. They took the tradition of ‘charity performance’ to the level of ‘international football’. Even though there were no official matches, between the spring of 1916 and the fall of 1918, they faced a series of serious opponents: France (1-4 and 1-3) in Paris; Italy (3-4) in Como, Modena (0-5) and Milan (6-4 defeat). In 1917, the most important ‘tour’ came along with no fewer than six matches between 15 and 29 November in de stadiums of Folkstone (1-6 versus Canada), Chelsea (London, 4-1 defeat), Everton (Liverpool, 1-2), Aston Villa (Birmingham, 1-4), Manchester United (1-1) and Celtic (Glasgow, 1-2): eight victories, one draw. The Front Wanderers seemed unbeatable. Thousands of ‘Belgian refugees’ supported them. A ‘Belgian newspaper in exile’, which was being distributed in London, described it as follows: ‘Full of strong emotions, a couple of thousand Belgians, who made their way to the grounds of the Chelsea football club, sat in the overcrowded stands and saw the infamous Red Devils – as they were known in peacetime – appear wearing our national team’s red sweaters.’

Armand had enjoyed it, as well as his teammates’ antics on the road. He watched them from a distance. He was always thinking one step ahead. Just like he would on the pitch, where he, being a defender, was praised for his fair-play. He avoided many duels because of his excellent anticipation skills and developed into an early master of positional play.

Belgian player Robert Coppée opened the score in the 6th minute of the 1920 Olympic football final, with a penalty kick past Czechoslovak goalkeeper Rudolf Klapka.

Belgian player Robert Coppée opened the score in the 6th minute of the 1920 Olympic football final, with a penalty kick past Czechoslovak goalkeeper Rudolf Klapka.This he knew for sure: without the Front Wanderers the Red Devils would never have been able to win the gold during the Antwerp Olympic Games after glories victories against Spain (3-1), the Netherlands (3-0) and Czechoslovakia (2-0). As he watched the dancing Belgians, he felt enormous pride.

From Front Wanderers to Olympic champions! Number one in the world! But the horror of the four-years Great War would never leave his thoughts. He remembered his brother. It was 2 September 1920.

This is a prepublication excerpt from Belgium, the first football world champion. The Red Devils, winners at the 1920 Olympic Games in Antwerp.