In 2013, people in Leiden considered the question, ‘Who is in charge of language?’ Asking that question is an answer in itself: nobody. Today, it is not quite clear who determines which norms to respect and which rules to adhere to. The government? The Academy? The Dutch Language Union? In a word: no.

Still, there is a distinct need for a norm. The Dutch Language Union, for instance, aims to eliminate the government’s and the educational system’s linguistic insecurity by offering a norm. Imposing rules is no longer an option – that is, if that ever was an option. The Dutch Language Union does not want to act as some kind of police officer. Rather, it wants to function as a signpost. Public service broadcasting in Flanders does not wish to set strict language standards, but it does want to disseminate language norms. It wants to set an example. Traditionally, elite groups – or “high-profile” communities, as they are referred to now – lead the way when it comes to promoting the norm. But who listens to elite groups in this day and age? Who can still be considered “high-profile”?

Joop van der Horst, professor of Dutch Linguistics, talks about the end of the linguistic culture in Europe

Joop van der Horst, professor of Dutch Linguistics, talks about the end of the linguistic culture in EuropeEver since around 1970, the powers that be and structures of authority have been deteriorating. The ongoing process of informalisation has also had an effect on language use. In this context, Joop van der Horst, professor of Dutch Linguistics, even mentions the end of the linguistic culture in Europe: in his opinion, we are currently experiencing the downfall and even the demise of standard languages. We are returning from strictly regulated language use to a much freer perspective on language.

Language is constantly in flux. In Dutch, for example, grammatical case suffixes, which determine the syntactic or semantic function of a word in a sentence, are long gone. “Jan slaat Piet” (“John hits Pete”) is completely different to “Piet slaat Jan” (“Pete hits John”); word order now determines a word’s function. We can find some remnants of the grammatical cases: “mij” (“me”) instead of “ik” (“I”). When it comes to grammatical cases, English is way ahead of Dutch, which in turn is way ahead of German. Whenever a transformation remains constant, we can call it change.

When it comes to grammatical cases, English is way ahead of Dutch

Is language falling into decay? According to some, this is true. However, every single generation of language users will claim this at one point or another. Let us consider the phrase, “Hun hebben gelijk” (“Them are right”). For all we know, in a few years’ time, this phrase will have become so widespread that it will become accepted, and therefore the rule. But, the possibility of this phrase becoming generally accepted one day does not mean we should accept it right now. For people today want to know what proper language is; people today have no use for an ‘anything goes’-attitude, for language relativism.

Others complain about the prevalence of loanwords in Dutch, especially the English ones. What brand-new challenge do our kids, who spend their time chilling, have to face? Obviously, these words are not always strictly necessary; there are plenty of perfectly suited Dutch words. Obviously, this can be blamed on laziness, current trends, snobbery and the urge to set oneself apart from the rest. Loanwords, however, do not pose a threat an sich: they do not affect the language’s structure. And then we have spelling, the aspect of language people are most sensitive about, yet not the most important one. Spelling is part of the outside appearance; it is a number of set agreements; and maybe we should interfere as little as possible with those agreements.

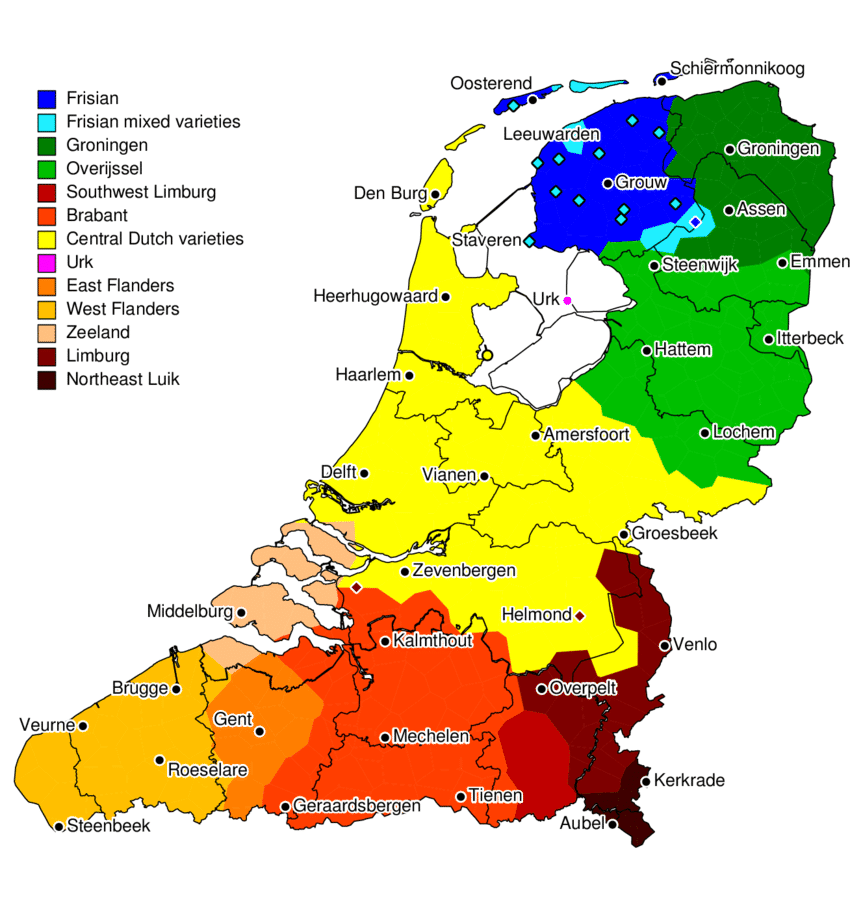

The 13 most significant groups among more than 350 language varieties spoken within the Dutch-speaking area

The 13 most significant groups among more than 350 language varieties spoken within the Dutch-speaking area© Illustration taken from 'Measuring linguistic unity and diversity in Europe', Erhard Hinrichs, Dale Gerdemann, John Nerbonne