The sheer complexity of the institutional architecture of Brussels must come as a surprise to the uninitiated. After all, the Brussels democratic institutions were set up in response to the linguistic tensions of the 1960s and 1970s between the French-speaking and Dutch-speaking populations. They were designed to take these considerations into account and are the result of a subtle political balance. Nowadays, there are changes afoot that are forcing Brussels to rethink its governance.

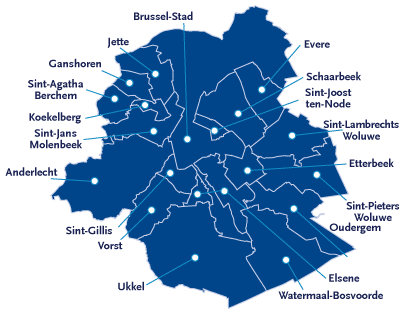

Brussels is a multilingual city located in Flemish territory, but nowadays French is actually the most widely spoken language. As the capital of Europe, Belgium, Flanders and the Wallonia-Brussels Federation, it has official bilingual French-Dutch status. The area in question consists of nineteen communes, which all have their own local council and an executive led by a mayor, with elections being held every six years. At this level of government, there are few systems in place to protect the Dutch-speaking minority.

Map of the Brussels-Capital Region

Map of the Brussels-Capital RegionIn Brussels, there are also two additional levels of government which are the result of the federalisation of the Belgian State. On the one hand, the Brussels-Capital Region covers the territory of the nineteen bilingual communes and is responsible for economic issues and town and country planning. It has a Brussels Parliament with 89 MPs directly elected every five years by universal suffrage and divided into two linguistic groups: 72 French-speaking and seventeen Dutch-speaking members of parliament. Within this parliament, the decisions are taken by a double majority, i.e. a majority of each of the linguistic groups. The regional government consists of a Minister-President (French-speaking) and of four ministers (two French-speaking and two Dutch-speaking). The Dutch-speaking minority is therefore very well protected at the regional level: over-representation guaranteed in terms of the number of MPs, power of veto through the double majority system, and parity within the government.

Logo of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital Region

Logo of the Parliament of the Brussels-Capital RegionBesides the Brussels-Capital Region, two Communities (French-speaking and Flemish-speaking) live side by side within the Brussels territory. They are responsible for anything relating to the population: culture, education, healthcare, etc. The Communities operate on a system of indirect representation: the 72 French-speaking members of the Brussels Parliament make up the French-speaking Community Commission (French-speaking Brussels Parliament); the seventeen Dutch-speaking members of parliament constitute the Flemish-speaking Community Commission (Dutch-speaking Brussels Parliament).

Whilst the Region has just been celebrating its thirtieth anniversary, Brussels itself has undergone profound changes. From a sociological point of view, Brussels has become much more international. Politically speaking, the tensions between the French-speaking and Dutch-speaking population have eased. The political representatives have largely accepted the institutional compromise that is based on two stumbling blocks: the outline of the Regional borders (nineteen communes) and the systems of guaranteed representation of the Dutch-speaking minority. Nevertheless, for some, the institutions described above, and originally designed to maintain a balance between the linguistic communities, no longer reflect the current reality of the city and have become somewhat of a straitjacket. The institutions lack transparency, the residents are not fully familiar with them and often bemoan their complexity. This apparently creates mistrust in the institutions; which are claimed to partition the local residents into multiple sub-communities, thus preventing Brussels from developing its own local citizenship.

For some, the institutions originally designed to maintain a balance between the linguistic communities, no longer reflect the current reality of the city and have become somewhat of a straitjacket

Challenging the Brussels institutional structure goes beyond the citizen framework and is also played out at the political level. In recent years, we have seen the bilingual lists mushrooming during the communal elections, but more recently also during the federal elections. During the 2019 regional elections, some parties circumvented the linguistic group rules. In order to maximise their chances of getting their members elected, they presented themselves in both groups, and parties with mainly French-speaking members chose to present themselves in the Dutch-speaking linguistic group.

Successive State reforms have led to a more profound transfer of the competencies of the Federal State towards the Region

Nevertheless, the institutional status of the Region has not remained completely unchanged. Over the decades, the Region has gradually asserted itself. Successive State reforms have led to a more profound transfer of the competencies of the Federal State towards the Region. Vice versa, we are noting a more subtle and slower transfer of the competencies of the communes towards the Region.

These changes, however, do not alter the essence of the Brussels institutional architecture, which is challenged by some. The three most frequent institutional big bang scenarios are: (1) the removal of the communal level and a complete transfer of the competencies towards the Region; (2) the merger of the smallest communes to reduce their number; (3) the demerger of communes into local entities.

Brussels Parliament building

Brussels Parliament building© Wikipedia

These proposals nevertheless systematically come up against the difficulty of having to (re)think governance to ensure balance within the community. Within themselves, the communes are presented as ramparts and any swing of the communes towards the Region is systematically interpreted as nibbling away at the power of the Dutch-speaking minority. Any major reform also requires constitutional change and therefore an intra-Belgian agreement. However, touching Brussels puts the overall balance at risk, to the point of collapse. These alternative proposals, therefore, present a type of legal and political impasse, and the Brussels institutional complexity still seems to be well and secure.

The most likely scenario would be that of a status quo in terms of institutional structure, combined with a more transparent sharing out of the competencies between the communes and the Region in favour of the latter.

Growing political dualisation

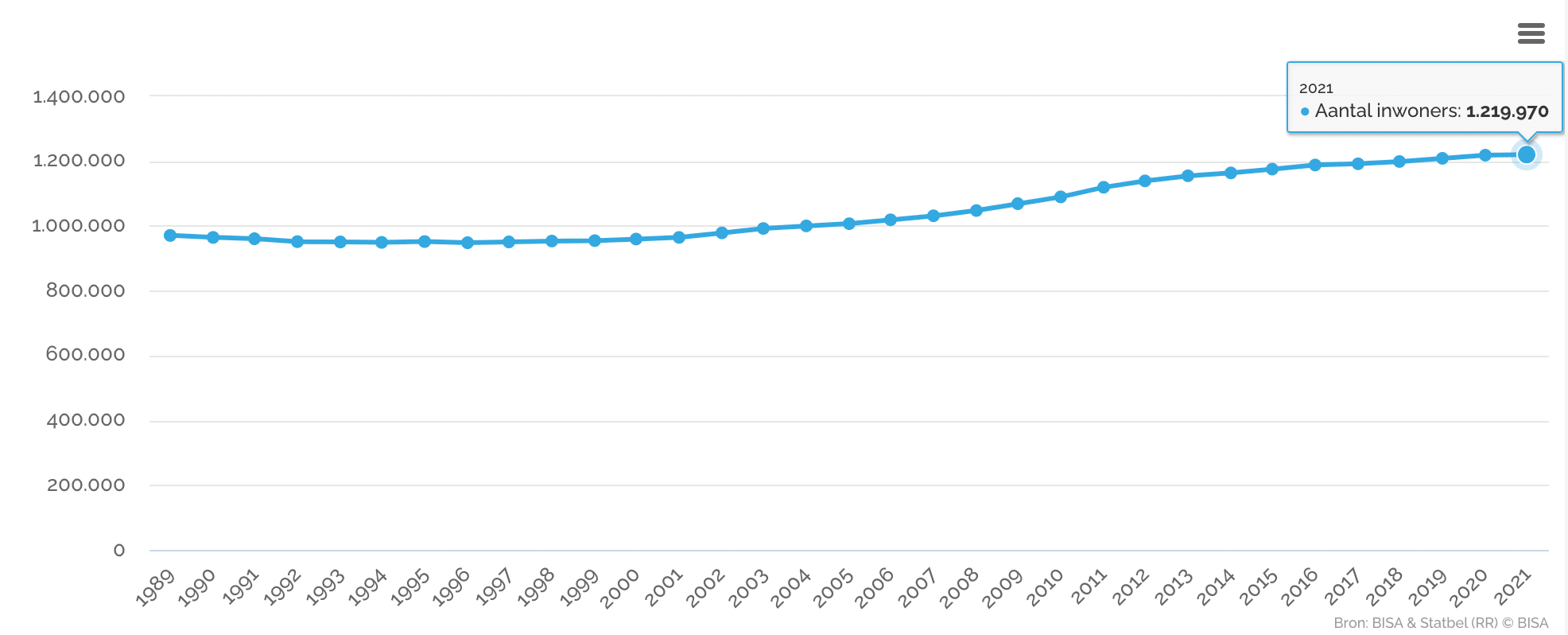

Even if the Brussels institutional structure has remained largely unchanged over these last decades, the same cannot be said for its social and political structure. From a sociological point of view, Brussels has transformed itself. Over a period of twenty years, it has gained the equivalent of 300,000 residents, and now has a population of 1.2 million. This demographic growth has mainly taken place in the northwest of the capital. Brussels has also become more international. In 2020, only 65% of its residents were of Belgian nationality. Almost a quarter (23%) hold the nationality of one of the European Union countries, and 12% are of non-European nationality.

Evolution of the number of inhabitants of the Brussels-Capital Region: 1989-2021 (in number of persons)

Evolution of the number of inhabitants of the Brussels-Capital Region: 1989-2021 (in number of persons)© BISA

These changes go hand in hand with a process of dualisation of the city. We see a socio-territorial fracture developing between the poor districts to the north and west and the rich districts to the south and east. Politically speaking, this evolution is noticeable in the local presence of the parties in Brussels. We are witnessing a type of intra-Brussels polarisation. The northwest is characterised by the domination of the parties of the left on socioeconomic issues, namely the socialist party (PS), which has recently been getting competition from the extreme left party PTB-PVDA. The southeast is dominated by the liberal party MR, which has been getting competition from the environmentalists (Écolo). The intra-Brussels territorial, socio-demographic and political division appears to be firmly ingrained. In terms of social cohesion, this dualisation in local presence is a major issue for the years to come.

The challenge of political participation and representation

This challenge of dualisation is further complicated by the issue of (re)connecting the citizens to politics. In Brussels, the electoral body differs depending on the polls, creating citizenships of variable geometry. Both Belgians and non-Belgians (subject to prior registration) vote in the local and European elections. The regional and federal elections are only for Belgian residents.

Brussels is becoming increasingly international.

Brussels is becoming increasingly international.© Urban Springtime

With the city becoming increasingly international, the segment of non-Belgian residents is on the increase. In 2012, this segment represented 29.7% of the Brussels population of voting age, and in 2018 this figure stood at 32.7%. In some communes, this proportion is close to reaching half of the potential electoral body. For example, Etterbeek had 44.8% of potential non-Belgian voters, Ixelles 46% and Saint-Gilles 48%. These voters are excluded from the electoral process when it comes to the federal and regional elections. At local and European level, few of them register to vote, even though this number is growing. Therefore, a large proportion of the Brussels population finds itself on the outside of the representative democracy process.

A large proportion of the Brussels population finds itself on the outside of the representative democracy process

In addition to this large proportion of ‘disqualified’ voters, there are those voters who consciously choose not to have their say. Even though voting is compulsory in Belgium, in the 2019 Federal legislative elections in Brussels there were 15-20% of abstentions depending on the commune. One must also take into account blank and invalid voting slips, which represent between 5-10% of voting slips submitted in Brussels in 2019. These numbers are on the up. And electoral participation has also been affected by the territorial dualisation movement mentioned previously. This is markedly lower in the north and in the west compared to the south and the east.

That is why the average of valid votes at the last two local elections in Brussels hardly exceeded one in two potential voters. In Ixelles and in Saint-Gilles, this number even fell below the 50% mark. One can therefore question the legitimacy of the representative institutions elected by such a low proportion of Brussels residents.

To respond to the social and political dualisation taking place in the area and to the Brussels population becoming disconnected from the institutions of representative democracy, Brussels is facing the challenge of having to rethink its governance. There is little room for manoeuvre, but this could be compensated for by a type of institutional engineering expertise which has developed over the years. Such a reform of governance in Brussels could offer an opportunity to think beyond the traditional representative institutions, for example, by acting as a testing ground for democratic innovation that includes all the Brussels residents in all their diversity.