Why Indonesia Never Really Became Dutch, but Is Now Becoming Anglicised

More and more English words are being borrowed and used in Indonesian, observes journalist Joss Wibisono with regret. Why are Indonesians making such a hodgepodge of their language? They were able to shake off Dutch colonialism thanks to their nationalism, but they have never had to fight for their language. The Netherlands did not impose Dutch in its colonies, so there was never any question of language nationalism there. And that is exactly why Indonesian is so open to anglicisation now.

There is something about the development of the Indonesian language that irritates me – it is being mixed with English. During the last forty years, more and more English words and terms have been introduced, and the need to translate them into Indonesian is declining. The number of people I would label as anglicised (keminggris

in Javan) is constantly increasing. As if all those borrowed words are generally accepted and everyone will understand them.

For example, six women spoke in a television programme about the bomb attacks in Surabaya in May 2018, in which women and children were involved. The first speaker used three English words in her first Indonesian sentence – nature, caring and loving. As if she wished to outdo her, the second speaker talked about indirect learning, in a very obviously Javanese accent. Why did they use those terms when there are perfectly good Indonesian words to express them?

© Jatim TIMES

Another example. During an election campaign for the Governor of East Java, in April 2018, there was a ridiculous mistake on a large banner – Meat and Great, instead of Meet and Greet. Why did the slogan have to be in English? After all, in Indonesian we say temu kangen.

Historical accident

Those who are familiar with Indonesian history probably assume that Indonesian is closer to Dutch than to English. After all, the Dutch ruled the archipelago for three centuries, so why do the Indonesians not speak Dutch anymore? In the small neighbouring country of East Timor, for example, the former occupier’s Portuguese language is still spoken. Is it true that the Dutch language was ousted by a surge of Indonesian nationalism that thoroughly wiped out the colonial legacy?

When Indonesian was still called Malay, the language cohabited amicably with the local languages and Dutch. I was brought up by my grandparents in Malang, East Java, in the 1960s and ’70s, hearing three languages around me, Dutch, Javan and Indonesian. My grandparents spoke Dutch with each other, because they had attended Dutch schools, and they taught me to speak and write the language. My first words may well have been not Javanese but Dutch. I learned Javanese in the street and was taught it later at school, along with Indonesian. I learned not to mix these languages. My grandmother stressed that many of those who spoke Javanese and Indonesian neither spoke nor understood Dutch. At school I later learned English and German, as well, but our teachers insisted that we should not mix them. To do so was evidence of poor linguistic abilities.

I am aware that my command of Dutch is an exception. My generation and that of my teachers barely speak Dutch anymore. Only the small group of mixed-race Indos, who chose to remain in Indonesia after independence, still speak Dutch. When we were alone together, I spoke Dutch with my three Indo schoolfriends, too. And when I went to a university in Salatiga in Central Java, in 1980, I was able to continue to speak Dutch with the Indos and the Dutch lecturers. But, even then, I noticed that the number of Indonesians who could still speak Dutch was declining rapidly, while the use of English was increasing substantially.

Language of the former coloniser

It was no effort for me to speak Dutch, when I moved to the Netherlands to work for the Indonesian section of Radio Netherlands Worldwide, in 1987. All I needed was a two-week course with the nuns in Vught. I did not have to write Dutch for my work, but I did have to be able to translate Dutch scripts into Indonesian.

In the Netherlands I became more and more interested in Indonesian history, especially what we call the Dutch period (zaman Belanda). I discovered that Indonesia is the only country where the language of the former colonisers is no longer spoken. The former British colonies Malaysia and Singapore have continued to speak English, and many of their authors write in that language too. In the Philippines, which was handed over to America by Spain in the nineteenth century, many writers likewise publish in English. Higher education in the former French colonies in the Maghreb is still bilingual, Arabic and French. The Moroccan writer Bensalem Himmich writes his novels in both French and Arabic.

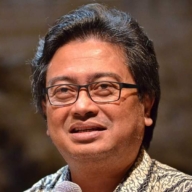

There were three Indonesian authors who published in Dutch, Raden Ajeng Kartini, Noto Soeroto and Soewarsih Djojopoespito.

There were three Indonesian authors who published in Dutch, Raden Ajeng Kartini, Noto Soeroto and Soewarsih Djojopoespito.In Indonesia, however, not a single writer publishes in Dutch now. In fact, it was already uncommon during the Dutch period. There were three authors who published in Dutch, Raden Ajeng Kartini (1879-1904), Noto Soeroto (1888-1951) and Soewarsih Djojopoespito (1912-1977). Their books were also recognised as literary works in the Netherlands, but I am inclined to regard then as an historical accident.

Youth pledge

Why is Indonesia the only country in the world that no longer uses the language of its former occupiers? Due to the historic fanaticism that I had brought with me from the country of my birth, I initially believed that Indonesian nationalism had driven out everything reminiscent of the Dutch. A particularly important factor in this was the Soempah Pemoeda – or youth pledge – taken by young nationalists in 1928. It called for one country, one nation and one language. However, I gradually changed my mind and have come to the conclusion that there is no historical basis for that idea.

I discovered, for example, that Soewarsih Djojopoespito published her novel Buiten het gareel

(Out of harness) in 1940, twelve years after the youth pledge. To be true to the pledge Soewarsih should have written in Indonesian. Why, therefore, did she write her nationalist novel in the language of the oppressor? Then I realised that my grandparents continued to speak Dutch until their deaths. In short, the youth pledge is not a conclusive explanation for the disappearance of Dutch from Indonesia.

In the midst of my search I saw an interview with Benedict Anderson on Dutch television. This well-known expert on nationalism pointed out that Indonesia was the only colony that was governed without the use of a European language. Moreover, Indonesia was not colonised by a state but by a company, the Dutch East India Company. That interview opened my eyes.

Profit maximisation was important for the company and costs in the colony had to be minimised. It was cheaper to teach employees Malay, the embryo of the Indonesian language, than to teach the population Dutch. When the Dutch East India Company went bankrupt, round 1800, the Dutch state took over the colony, retaining the company’s language policy. Although Europeans in the capital Batavia spoke Dutch and ousted Portuguese as the second language after Malay, the use of Dutch by the population was not encouraged.

The excuse for that was that Indonesia already had a common language – Malay. But that was also the case in the Maghreb, where Arabic was the common language, but the French nonetheless imposed their own. In the French colonies people had to be educated in the same way as in the fatherland, and that mission civilisatrice meant that not only must education be spread, but the French language too. The French economist and essayist Paul Leroy-Beaulieu put forward the idea in 1874 and in 1890 Paris embarked on a policy of making French the second common language in its colonies. This gave French the chance to take root and it continued to be the second language, alongside Arabic, even after independence. French also connects the Maghreb to the international world. The other colonial powers – England, Spain and Portugal – implemented the same policy.

Elitist language

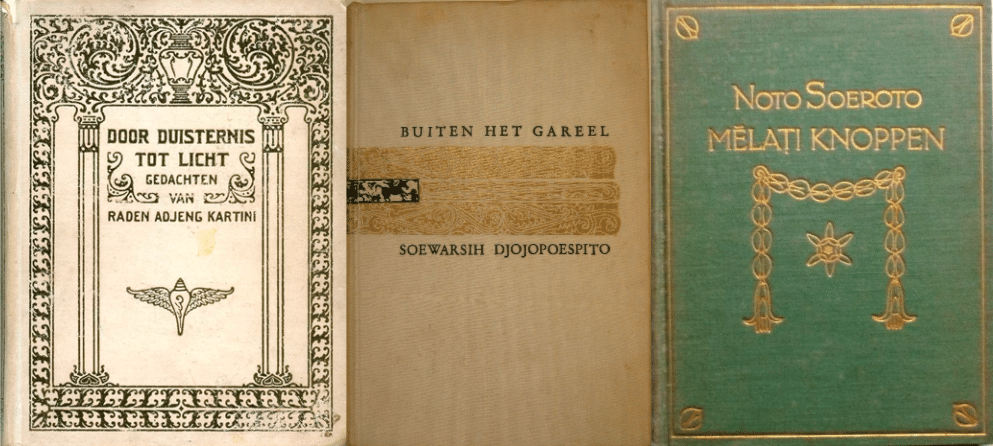

In the early twentieth century, the Netherlands saw that French, English and Spanish had become the common languages in many regions. Intrigued by this, The Hague adopted a new approach and launched the Ethical Policy. In 1914 Dutch education was introduced in the Hollandsch-Inlandsche School (HIS), a primary school for children of the local elite. But it was too late and a rather half-hearted gesture. Dutch continued to be the second language, not the working language, at the HIS. On the other hand, the Europeesche Lagere School (ELS, the primary school for children of European origin) was, from its foundation in 1817, completely Dutch-speaking. Non-European children were sometimes admitted to the ELS, but they were the children of prominent members of the aristocracy, never ordinary middle-class children. One of these, R.A. Kartini, was the regent’s daughter. Thanks to the ELS she became extremely good in Dutch, as is clear from the letters she sent to friends in the Netherlands. Kartini was an exception though, not least because she had such a talent for foreign languages. Apart from Kartini and her sisters Dutch remained an elitist language for the local population.

ELS (European primary school), Djawa Tengah, 1899

ELS (European primary school), Djawa Tengah, 1899In the end, Dutch-language education for indigenous children lasted less than thirty years, until the Japanese occupation in 1942. It was impossible for Dutch to take root in that time and independence, in 1945, put an end to it once and for all.

Dutch language policy failed to make Dutch an international language because of its lack of vision. There are fewer than 25 million Dutch speakers, in the Netherlands, Flanders, Suriname and the Caribbean. Had Indonesia become Dutch-speaking as well, there would be 300 million. At one time that was a real possibility, but the mentality of the Dutch East India Company prevented it.

The mentality of the Dutch East India Company has prevented Indonesia to become Dutch-speaking

In 1939, French professor George-Henri Bousquet painted a sombre portrait of Dutch in the largest of the Netherlands’ colonies in his book, A French View of the Netherlands Indies (orig. title La politique musulmane et coloniale des Pays-Bas). “Fifty years hence the Dutch language would cease to play any sort of social role in what had been Dutch territory for more than three hundred years”. In fact, Bousquet was generous. By the 1970s, even earlier than he had predicted, Dutch played almost no role anymore in Indonesia.

Dutch tourists are happy when they hear Dutch words like handdoek, asbak or schokbreker (towel, ashtray and shock absorber). But what they do not know is that there are fewer and fewer Dutch loanwords left in Indonesian now. For example, the younger generation now uses diskon

(from the English discount) instead of the Dutch karting and says londri (from laundry) instead of wasserette. To speak to Indonesians the Dutch must therefore use a third language – English. That is different in the Maghreb and the other ex-French colonies, where tourists are still greeted in fluent French. And when inhabitants of those former colonies go to France, they can also speak French.

Malian Mamoudou Gassama, who arrived in France without documents, became world-famous in May 2018, when he heroically saved a child hanging from a balcony. President Macron received him at the Elysée – and obviously they conversed in French. After less than a year in the Netherlands there is not a single Indonesian immigrant that will speak such fluent Dutch as Gassama spoke French, even if he or she has valid documents.

French President Emmanuel Macron meets Mamoudou Gassama.

French President Emmanuel Macron meets Mamoudou Gassama.Paradoxical

The fact is, then, that there has never been any real rivalry between Dutch and Malay (later Indonesian) in the archipelago. The colonial language never ousted the colony’s own language. People could continue to speak Malay and did not need to speak the language of their oppressors. Moreover, the Office for Popular Literature, which was set up by the Dutch, even published books in Malay and other regional languages, and helped to develop and standardise the Malay language. The fact that it oversaw the spelling that was introduced in 1900 was not seen as a constraint.

Government of the colony was different though. Dutch colonialism was generally seen as an occupation of Indonesian territory and the nation. The three elements of the Youth Pledge were country, nation and language. Of these it was the first two, in particular, that were dominated by the Netherlands. Indonesians were third-class citizens in the colony, after the Europeans and foreign Orientals, but their language was not subjugated. That is the key to the anglicisation of Indonesian. Because Indonesians could continue to speak Malay, and Dutch was never imposed on them, language nationalism had no role in their struggle against Dutch domination.

Language nationalism had no role in Indonesians’ struggle for independence

Indonesians are still extremely sensitive about their territory, however. When the International Court in the Hague recognised Malaysian sovereignty over the islands of Sipadan and Ligitan, in 2002, the Indonesians angrily shouted “NKRI harga mati”, which means something like “Unitary state to the death”. The judgement was seen as a threat to the territorial integrity of the country. Likewise, there was a fierce reaction in 1999, when 78.5 percent of the East Timorese population voted for independence from Indonesia. The government is also often criticised from a nationalistic point of view. For example, there was a great deal of criticism of President Joko Widodo, because of Indonesia’s high foreign debt and consequent increasing dependence on other countries.

The influence of foreign languages is never criticised though. The fact that fanatically nationalistic Indonesians greedily adopt words from foreign languages might certainly be called paradoxical. Evidently Indonesians do not feel the need to stand up for their own language, so is it still possible to call a halt to anglicisation? When languages are mixed, one of them must go. And the less cosmopolitan public will give in. Will the realisation dawn that too many English words have taken root in Indonesian? Or will the national language have long since become Indoglish by then? I hope I will never see that happen.