Why Reynard the Fox and Flanders Are Inseparable

No other Middle Dutch text has meant so much to so many as Van den Vos Reynaerde (variously retold in English as Of Reynaert the Fox, Reynard the Fox and The History of Reynard the Fox, etc.), a dramatic literary cycle about the relationship between the individual and society, written by the otherwise unknown author Willem. Why has this story remained so popular for centuries? And how have so many textual researchers set about getting their teeth into the fox’s adventures? That is what medievalist Frits van Oostrom examines in his book De Reynaert. Leven met een meesterwerk (The Reynard. Living with a masterpiece), in which he also ties the animal epic to his own career in Middle Dutch literature. We present an excerpt adapted from De Reynaert. In it, Van Oostrom shows how it was that the world’s most famous fox became so embedded in Flanders’ collective memory.

In Flanders, far more than in the Netherlands, one grows up with Reynard. For many he is a family friend. According to the charismatic priest, poet, teacher and public intellectual Anton van Wilderode (1918-1998), the Reynard story was actually a “mirror of the Flemish soul”, a heroic epic about the ordinary man who must stand up to the elite and those in power. Here, dear to Flemish hearts, is a short scene with the little dog Cortois. King Noble’s court has only just begun to hear the first grave accusations made by Isengrim the wolf against Reynard. According to Isengrim, the fox had urinated on his children and, worse still, assaulted his wife. They are serious charges made by one baron against another, culminating in a rhetorical climax, “Mr. King, Reynard has done me so much wrong that even if all the cloth woven in Ghent were parchment, it wouldn’t be enough to write it all down!”

Isengrim’s accusations are still resonating when Cortois decides he should add his bit too. This courtier (“courtois” in French) expresses his complaint in French. He claims that Reynard had once stolen a sausage from him. Coming after Isengrim’s accusations, this is as if bicycle theft were being added to the charges against a serial murderer. But then it turns out that Cortois had himself stolen the sausage, from Tybert the tomcat at that. “Those who steal from someone else, should not complain when someone steals from them”, interjects the tomcat sharply. In the rest of the proceedings, Cortois’s complaint, made in his affected-sounding French, was to play no further part.

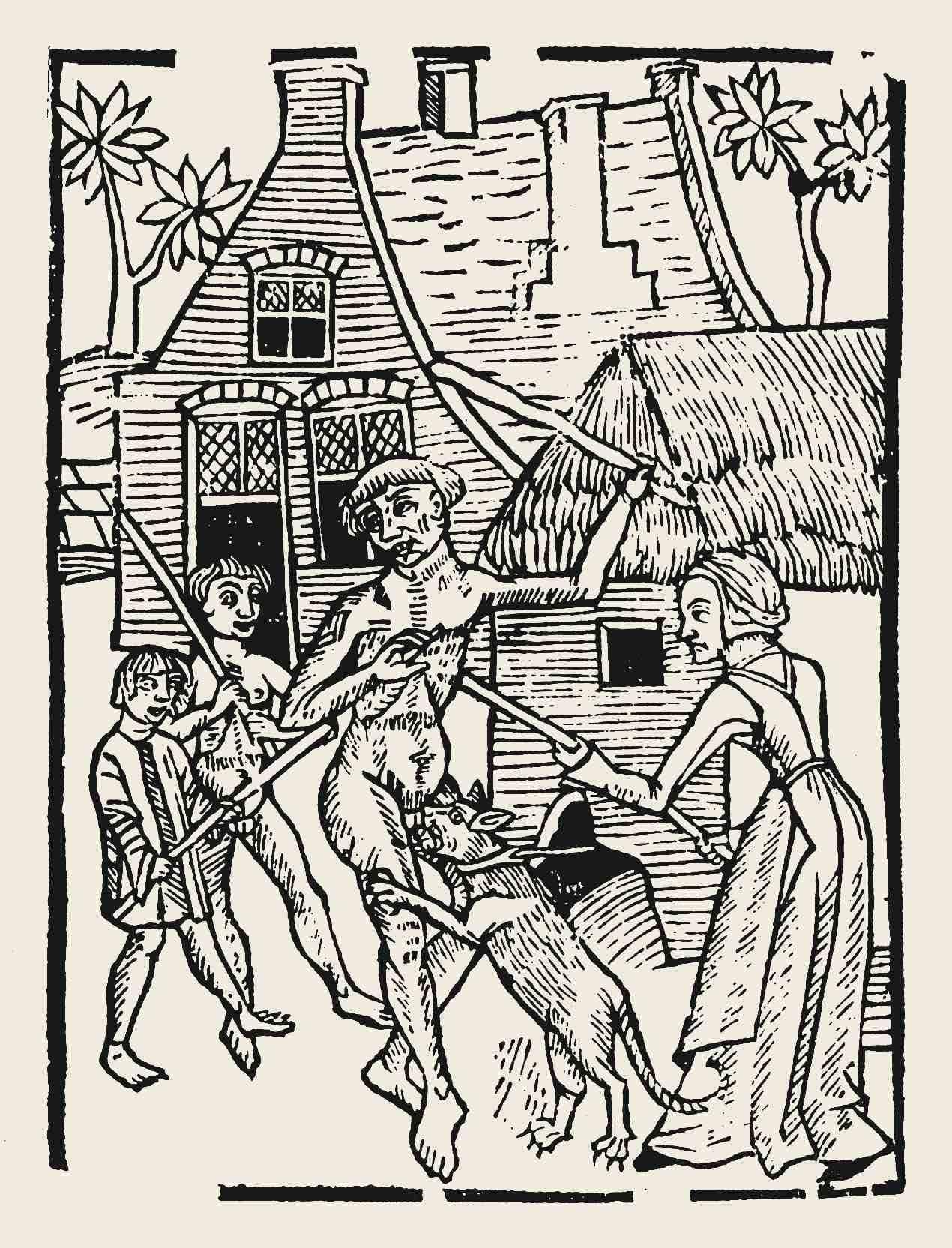

The famous vicar scene with Tybert the tomcat in a woodcut depicted in an incunabula of the Reynaert.

The famous vicar scene with Tybert the tomcat in a woodcut depicted in an incunabula of the Reynaert.Rarely has a minor character managed to become such a national hero. Cortois’s failed performance is still sniggered at in Flemish cafés. In academia too, for that matter. At an international colloquium on the animal epic, in 1972, a Flemish contributor suggested that, in the “tripping cadence” of the verses Willems dedicated to Cortois, “the light sound of French” resounded, and that this short scene makes fun of “certain individuals’ infatuation with French. Cortois is a bootlicker”. In one of his poems Van Wilderode sighs, “In Brussels, Cortois would have been proved right long ago.”

Meanwhile, the Reynard mentality has remained strong among Flemings for nearly two hundred years and shows little sign of wearing off. The Reynaert epic stands unwavering at the top of the pyramid that is the Flemish canon, alongside such luminaries as Willem Elsschot and Louis Paul Boon. In a certain sense Willems is even the focal point of this trio. Boon’s work is teeming with references to the Reynaert. In Boon’s opinion, Reynard himself is a republican anarchist and role model for ordinary people in Flanders, “who are wise enough to disparage everything that represents the Establishment”. Willem Elsschot was the pen name of Alfons de Ridder, who chose his literary first name as a mark of respect for the Willem who wrote the medieval Reynaert verses. “The only books I have in the house are the Bible and the Reynaert”, Elschot is said to have declared. He knew whole sections of the Reynaert stories by heart. On his seventieth birthday his Dutch colleague, M. Nijhoff, addressed him as Reynaert the Knight and Willem the Fox. Elsschot was clearly deeply moved.

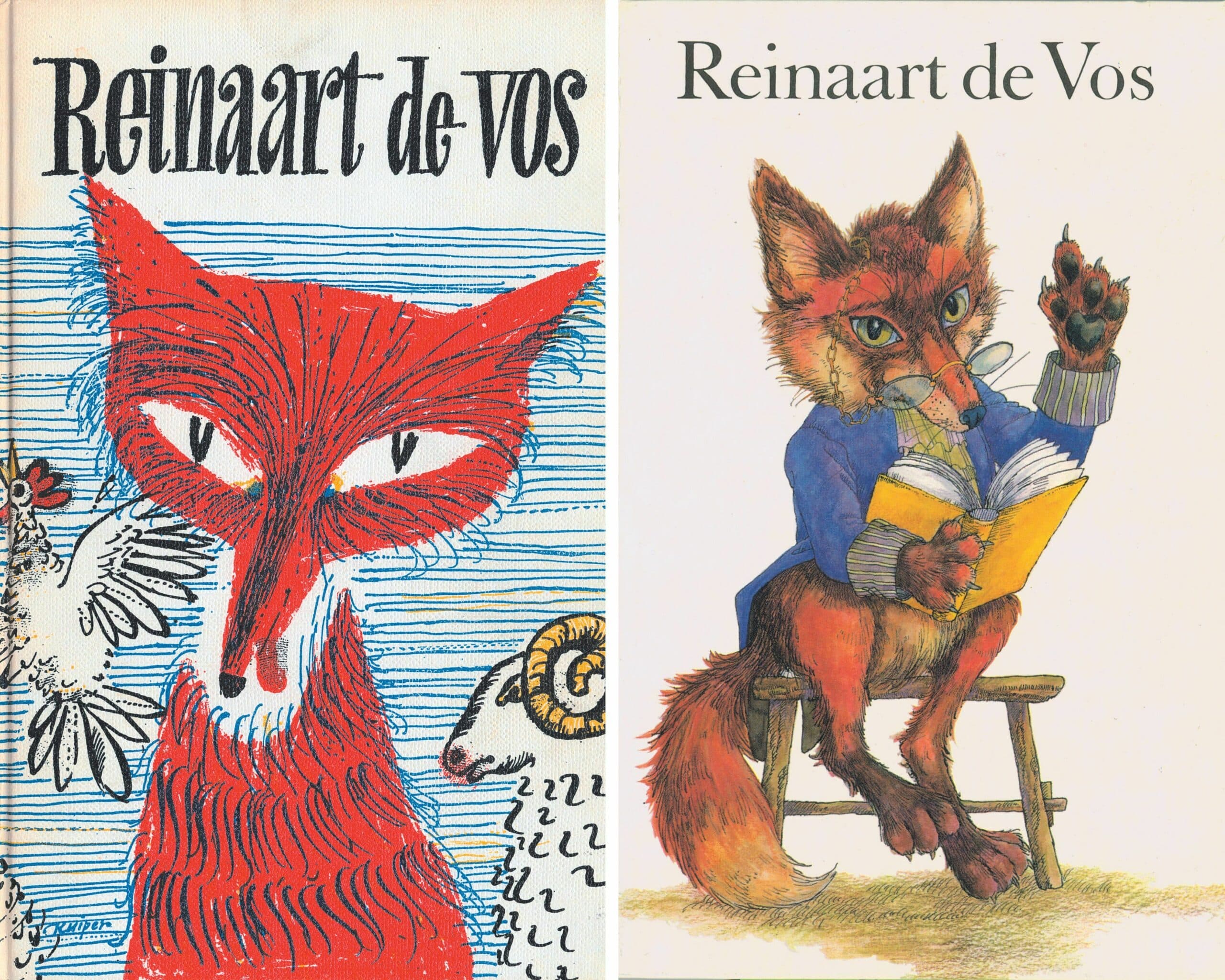

Two covers of Reynaert editions in the Oud Goud series. The book on the left started Frits van Oostrom's fascination with the fox.

Two covers of Reynaert editions in the Oud Goud series. The book on the left started Frits van Oostrom's fascination with the fox.There is hardly any big name in Flemish literature that did not relate to Reynard. Gerard Walschap, Richard Minne (“I am Reynard, Reinaert ben ik”), Felix Timmermans, Stijn Streuvels – who published nearly twenty Reynard books – and Guido Gezelle. Conspicuously absent from this line-up is Hugo Claus, yet he lived for a long time in Reynard’s own city of Ghent. Was Reynard too obvious a choice for him perhaps? Nonetheless, Reynard is part of the DNA of Flemish writers, and that applies to contemporary writers like Stefan Hertmans and Tom Lanoye as well. In his youth, the latter had a minor role in the powerful sound and light show Reynaert on the main square of Sint-Niklaas in May 1973. As one of hundreds of extras – there were eight hundred participants, including six hundred on the stage! – fourteen-year-old Tom Lanoye, referred to in the programme as Lannoy, played a little fox clad in black tights. His main text was “Thank you for the chicken, O Lord!” The Reynaert had become dear to him thanks to Van Wilderode’s lessons at St Joseph’s Minor Seminary in Sint-Niklaas. In 2020, Tom Lanoye commented, “Unforgettable years, a reputable school of learning, I wouldn’t have missed them for anything.”

Flemish Movement

Flemings’ unwavering loyalty to Reynard had its roots in Jan Frans Willems (1793-1846), the patriarch of the Flemish Movement, the only non-violent revolutionary movement in nineteenth-century Europe. “My fatherland is not too small for me”, was his motto, and “The language is all the people”. As long as there was unity with the Northern Netherlands this conviction had clout, but after the secession in 1830 – much regretted by Willems – Dutch became weaker in comparison to French. As a civil servant, Jan Frans Willems had to face demotion, and was transferred from a prominent position in Antwerp to a marginal one in the then village of Eeklo. Making a virtue of necessity, Willems devoted what was in practice his retirement there to studying early Flemish history and literature. Philological vengeance was to prove sweet.

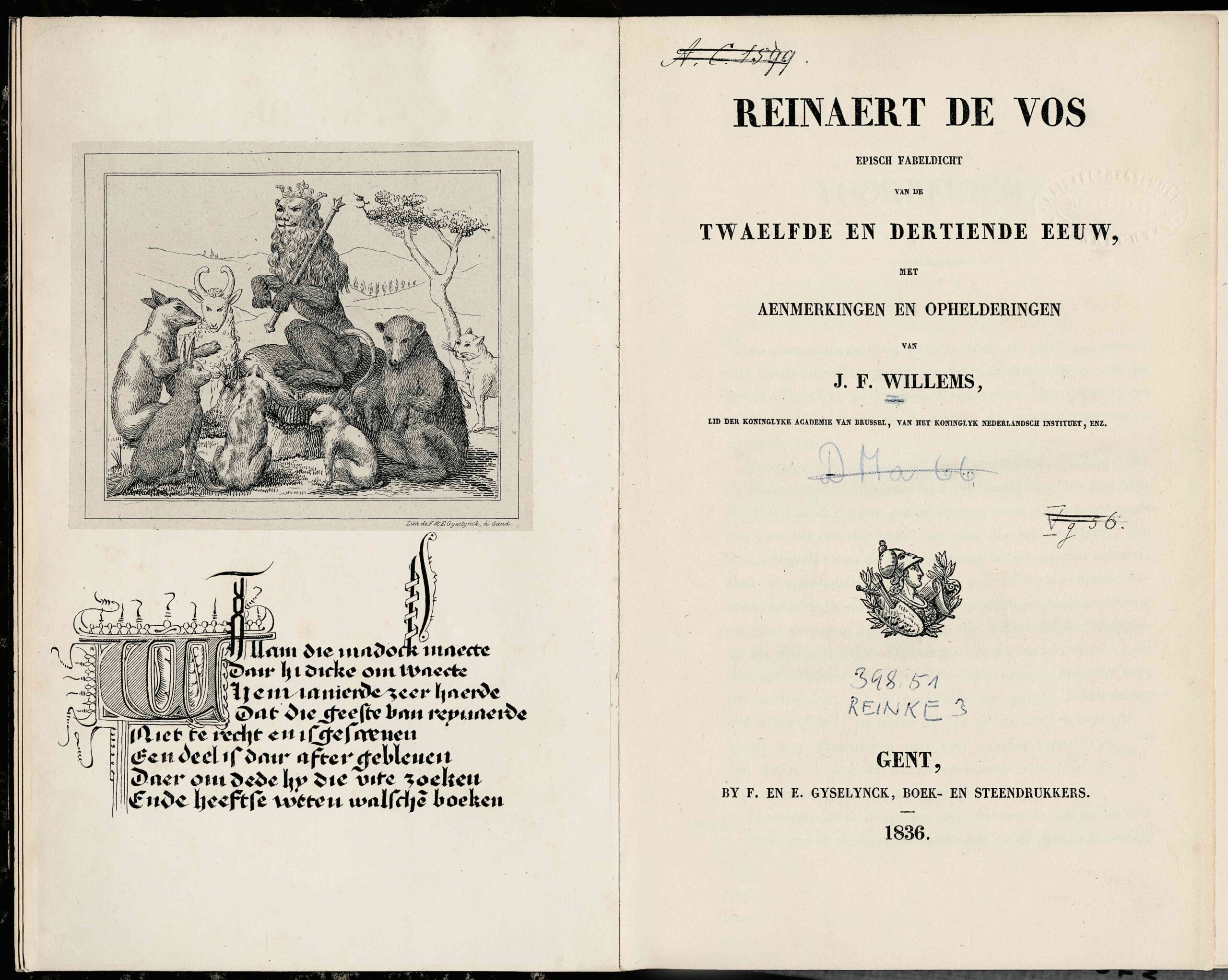

Flemings’ unwavering loyalty to Reynard had its roots in Jan Frans Willems. This is his Reynaert edition.

Flemings’ unwavering loyalty to Reynard had its roots in Jan Frans Willems. This is his Reynaert edition.In 1833, Willems wrote from exile – that was how it felt to him – a couple of articles about the Reynard material, which he had learned about from correspondents in Germany (Grimm) and the Netherlands (Bilderdijk). Willems’ conviction was that the Reynard stories had their origins in twelfth century Flanders and had spread from there to the rest of Europe, with Van den vos Reynaerde as their literary highpoint. After Dante’s Divine Comedy, Willems considered this Flemish version of the Reynard tales to be the best epic poem that the Middle Ages had given Europe. “And this poem is Belgian! But the Belgians don’t know it!”

Jan Frans Willems published the first edition of the Reynaert in the Dutch-speaking region, in 1836. This was preceded however by another project, a contemporary rhyming version from Willems’ own hand, to increase familiarity with the Reynard stories in Flanders. Was this apparently illogical sequence – first the adaptation and then the original – a conscious choice? Did he want to touch the emotions first and then to satisfy the intellect? Whatever the case, it would turn out to be a stroke of genius for the Flemish Movement. If Willems’ first work had been his scholarly edition, its Middle Dutch would certainly have been greeted with reverence but would have stood a good chance of being buried in libraries as patrimony. Rewritten in nineteenth-century language, the ancient text spoke much more directly to Flemish hearts. It was all the more successful thanks to Willems’ pliant rhymes, on which he worked long and hard according to the journal he kept. The result couches the old verses of the Reynaert in supple metric, with a mouthful of Middle Dutch here and there. Notice the rhyming couplets in Willems’ verse:

’t Was omtrent de Sinxendagen.

Over bossen, over hagen

hing het groene lenteloof.

Koning Nobel riep ten hoov’

al wie hij, om hof te houden,

roepen kon uit veld en wouden.

Vele dieren kwamen daar,

groot en klein, een bonte schaar.

Reinaert vos, vol slimme treken,

bleef alleen het hof ontweken;

want hij had te veel misdaan

om er heen te durven gaan.

It was the feast of Pentecost,

The lion, noble King of all beasts,

wished to hold open court over the

days of the feast.

Summons to court was made

throughout his realm, and every

animal was commanded to appear.

All beasts came, both great and

small, except Reynard the Fox.

Reynard knew that he was guilty

on many counts […].

So he didn’t dare show up.(1)

Jan Frans Willems published his Reinaert de Vos naer de oudste beryming (Reynard the fox after the original verses) in 1834, the year in which he and his wife lost two children. The foreword reads like a Flamingant manifesto for the freeing of the Flemish language from its shackles. Willems endowed the book with the wish that it might “contribute to the revival of such a beloved language, at a time when our country is inundated with so much French scum!”

Consequently, thanks to Willems’ Reynaert, the Flemish Movement’s noble cause acquired an icon as well as an ideal, four years before De leeuw van Vlaanderen (The Lion of Flanders). Reynaert roused sympathy for the language even from King Leopold I. According to a letter from his secretary, the King read the text in a single sitting “avec un plaisir dont il ne s’était pas fait d’idée jusqu’alors” (with a pleasure he had never imagined until now). Having read it, His Majesty promised from then on to encourage the use of Dutch. Buoyed by the attention and at Willems’ own insistence, in early 1836 the Belgian government released what was at the time a substantial budget for the purchase of a Reynaert

manuscript that was coming up for auction in London. The manuscript has been in the Royal Library in Brussels ever since. These days that might seem the obvious habitat for the book, but at the time it was a culture-political act of the highest order, coming from a government that had until then been oriented exclusively towards the French language.

Thanks to Willems’ Reynaert, the Flemish Movement’s noble cause acquired an icon as well as an ideal

Jan Frans Willems truly got what he deserved. Understandably enough, for the good of his fatherland and his mother tongue, he had exaggerated the Flemish roots of the European Reynard stories. In particular, Jan Frans Willems had, by no means accidentally, ignored the creative contribution of French. After all, the main source of Van den vos Reynaerde was the Old French Roman de Renart, twenty-seven short tales about the fox Renart

and how he scored points off everyone. Nonetheless, Willems’ romantic, national jubilation was certainly not completely misplaced. After all, Flanders has been the Reynard-land par excellence for centuries. Or, as a standard work about the Reynard stories puts it, Reynard the Fox seems to strike a deeper chord in this region than elsewhere in Europe.”

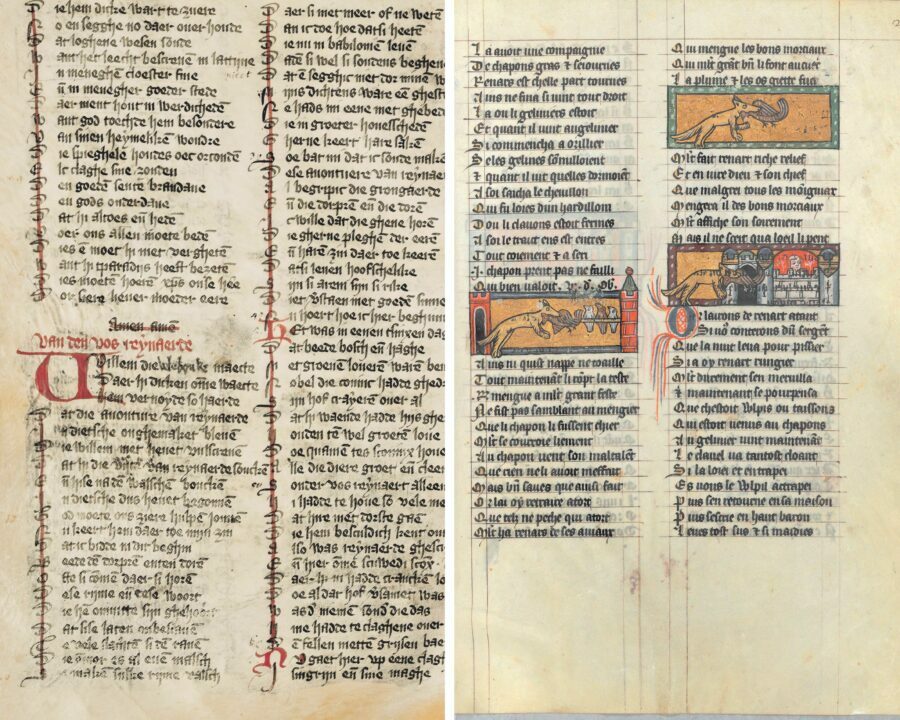

The Comburg manuscript that includes the Reynaert story and the manuscript of the Roman de Renart, the Old French main source of the Reynaert.

The Comburg manuscript that includes the Reynaert story and the manuscript of the Roman de Renart, the Old French main source of the Reynaert.‘Understandable Flemish’

The provenance of the Reynaert resonates clearly in the preserved Middle Dutch text. Its language and accent are unmistakably Flemish. Dialectologists point to typically Flemish forms such as the very frequent ic bem for ic ben (ik ben/I am) soe for si (zij/she) and the – for non-Flemings – famously treacherous h-: as in hu for u (you). Philologist Maurits Gysseling even saw specifically Ghent spelling in the use of h for ch as in nohtan (nochtans/nevertheless), met rehte (met recht/rightly). Such cases are, of course, fodder for connoisseurs, but the sense of linguistic affinity with the Reynaert runs deep with many a Fleming.

Someone for whom this was evident, almost a moral question even, was Stijn Streuvels (1871-1969). Born in Heule, in West Flanders, to a mother from Bruges (the sister of Gezelle) and a father from East Flanders, he recognised himself centuries later in Willems’ language. Although he had left school without a diploma, Streuvels celebrated this linguistic affinity in his own retelling of Reynaert, “rewritten from Middle Dutch in understandable Flemish”.

The sense of linguistic affinity with the Reynaert runs deep with many a Fleming

Streuvels published three versions of this retelling, in many editions, over a period of more than fifty years. Each time he spiced it up with new ingredients from Middle Dutch, in Flemish of a highly personal nature. Streuvels’ mixture of medieval and modern language proved to work well, including for the finely tuned ear of Albert Verwey, the leader of the Dutch Tachtigers (a movement of young writers from the 1880s). In response to Streuvels’ first retelling of the Reynaert, Verwey wrote to him from Noordwijk, “Your language is much closer to it than ours.”

And so it was. Words like penne and stemme are frequent in Streuvels’ versions and are pure Middle Dutch, even though they do not appear in the Reynaert. But Streuvels did borrow some other words directly from this text, including zonne, noene, menigerhande, geerne, bake, wise, and so on. Still others he created for the occasion in the style of Middle Dutch, for example ’t wonderde hem; met mij getienen; zoo luide dat er nooit beest in zijn woede zulken schreeuw gesmeten heeft. Sometimes it feels a bit artificial and Streuvels’ language play degenerates into pidgin Middle Dutch: te passe zijn,

het eekhoorn, een luttel tijts, or rutselen for roetsjen. But, apart from occasional excesses, the affinity between Streuvels’ literary vernacular and that of the medieval Reynaert is certainly not auditory delusion.

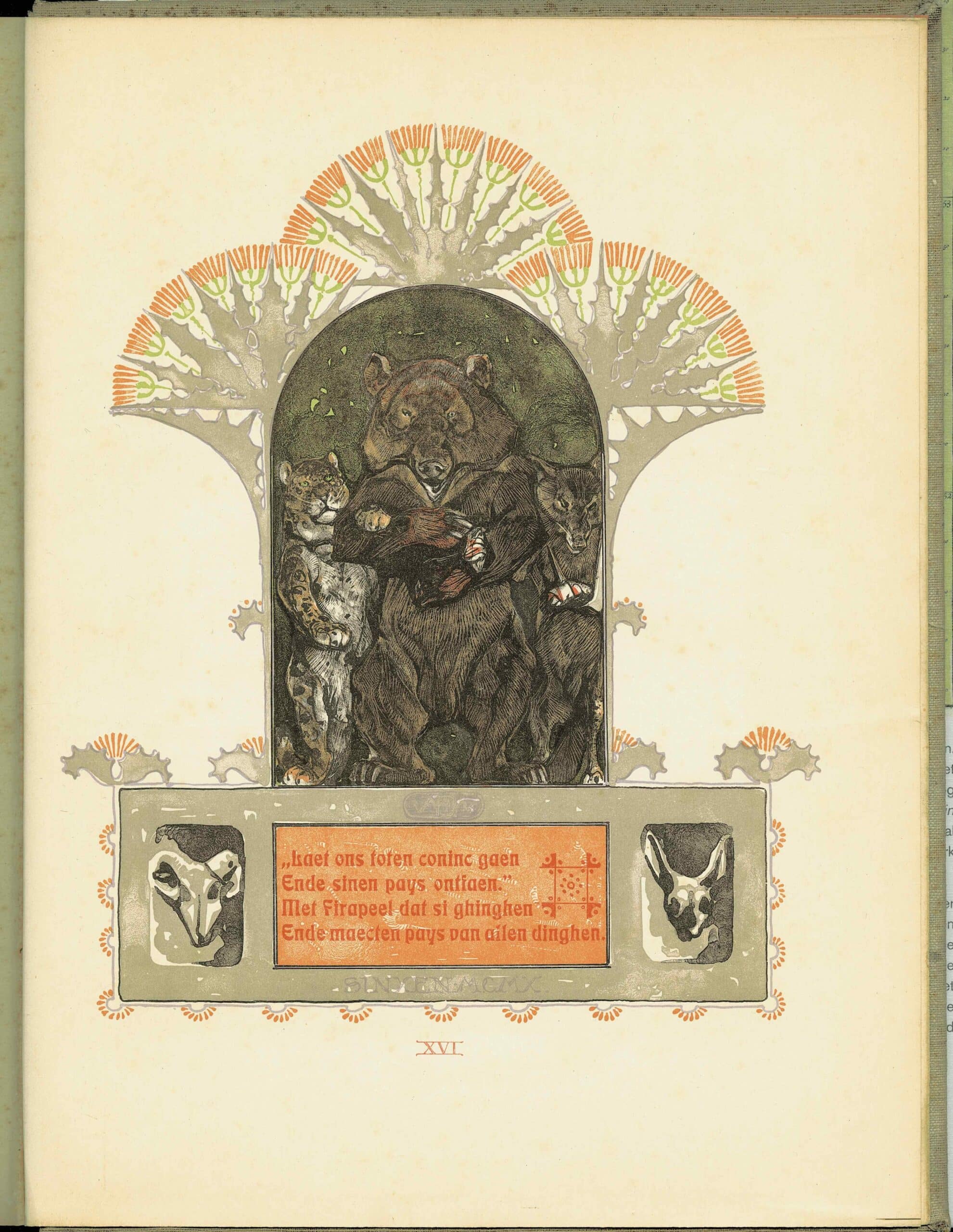

Concluding lines of the Reynaert in the deluxe edition of Stijn Streuvels' adaptation, illustrated by Bernard Wierink.

Concluding lines of the Reynaert in the deluxe edition of Stijn Streuvels' adaptation, illustrated by Bernard Wierink.Likewise, the Reynaert’s Flemish provenance can be heard equally loudly and clearly in the flood of place names that the ancient text brings up, revealing intimate familiarity with Flemish geography. These are not limited to well-known names like Ardennes, Ghent and Leie either. Van den vos Reynaerde also names relatively obscure places like Hyfte, Hulsterloo, Elmare, Belsele and Absdale. It is more than clear then that Flanders is the region where the fox’s story takes place. More particularly, many of the place names belong to the Waasland, and Reynard himself talks at one point of the “sweet Waasland” (“in Waes, int soete lant”). The etymology of the region’s name probably goes back to Middle Dutch wase or mud – an appropriate name for a habitat conquered during the Middle Ages from a wasteland of primeval forest, water and drifting sand. Numerous places in the Reynaert proclaim a detailed knowledge of the Waasland and adjacent eastern Zeeuws-Vlaanderen.

Reynaert beer

Reynard and Flanders cannot be separated. We should certainly not make a border dispute out of our association with the Reynaert, but if we do choose a position at “the ravine between Essen and Roosendaal”, as Ludo Simons called it, the Netherlands has played a big role in the academic study of Reynaert. For genuine love of Reynard, however, one has to look to Flanders. That is where the Reynaert is most strongly anchored in the collective memory, as well as in all sorts of artefacts.

A wonderful, enamelled Reynard spoon, preserved in Boston, was made as early as 1430 in a Flemish workshop. A luxurious rosewood writing cabinet, inlaid with scenes from the Reynaert, was produced in Antwerp around 1700. In 1913 it was auctioned in Vienna and has since disappeared without a trace. In contrast, only a decade ago, six impressive murals came to light in the late-nineteenth-century Antwerp patrician residence of the Flamingant Max Rooses. They were intended, by the man who commissioned them, partly as a tribute to Jan Frans Willems. For more limited budgets there is, of course, Reynaert beer and even a pale red, velvety soft Reynaert rose, Rosa Reynaerdiana Wasiana.

Furthermore, in the Flemish regions, Reynard has also given his name to a satirical magazine, published from 1860 to 1868, with the subtitle Een zondagsblad voor verstandige lieden (A Sunday paper for sensible people), a radical newspaper published during the same period called Reinaert de Vos, Afbraak der kasteelen! (‘Reynard the Fox, Destruction of the Castles!), a rebellious radio station, a publishing house and the royal theatre company Reynaert. The fox is widely present in public spaces, too, from all manner of park sculptures to the EU-funded Reynaertland swimming pool complex in Hulst. And, if you drive along the E34 motorway, you will see a sign on the verge indicating LAND VAN WAAS (i.e. Waasland) and the silhouette of the world’s most famous fox.

By no means all the road users, Sunday swimmers, beer drinkers and rose growers will have read the Reynaert themselves, let alone in Middle Dutch. But the text does live in them. It makes people feel “part of a bigger story”, as Flemish journalist and writer Chris de Stoop aptly puts it in Dit is mijn hof (2015, This is my garden), which is also full of references to the Reynaert. With good reason in this case, because Jan Frans Willems was right. There is no doubt that Van den vos Reynaerde is thoroughbred Flemish heritage, and that without Flanders there would have been no Reynard. Or at least not this one.

De Reynaert. Leven met een meesterwerk (The Reynaert. Living with a masterpiece) by Frits van Oostrom is published by Uitgeverij Prometheus in Amsterdam.