Why the Belgian Resistance Deserves More Attention

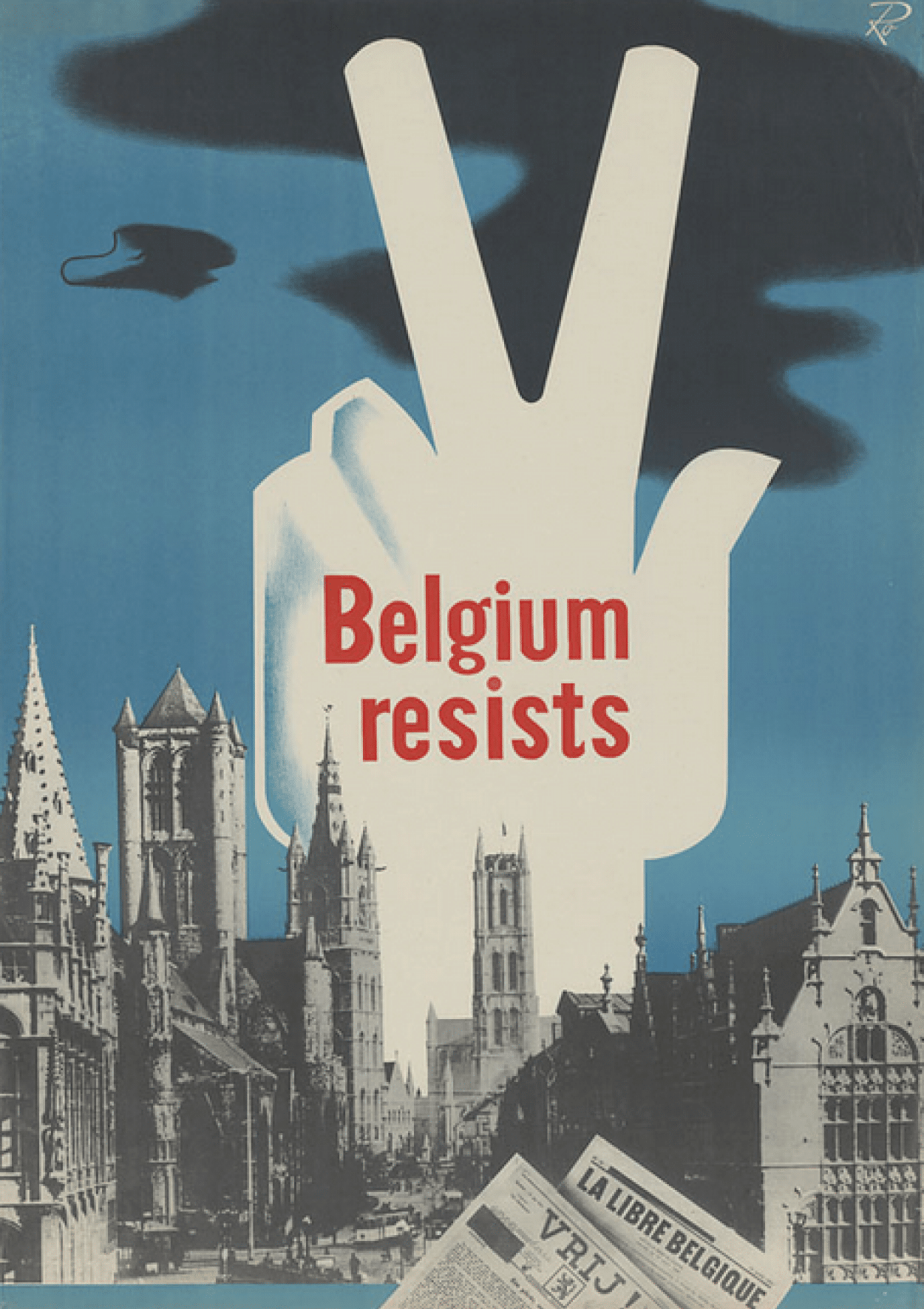

The importance of the resistance during World War II doesn’t form part of the Belgian collective memory. The political and moral legacy of those who resisted the German occupier has been largely forgotten. That’s remarkable, as the resistance represents an impressive achievement. It deserves a more prominent place in the remembrance of the war.

In 1942 Mayer Gulden lives with his wife Pescha and two children Dyna and Mozes at De Berlaimontstraat 14 in Deurne, Antwerp. The local police arrest the mother and two children in the night of 28-29 August 1942. In early September they are murdered in Auschwitz. Mayer himself escapes and goes into hiding with another Jew in the house of Emiel Acke and Valerie Duerinckx, his neighbours. Emiel and Valerie are risking their lives for this act of resistance. After the war they receive no recognition whatsoever. The policemen who arrested Pescha and her children were themselves arrested by the occupier in January 1944.

Part of the monument to the memory of deported Antwerp policemen, Deurne (Antwerp)

Part of the monument to the memory of deported Antwerp policemen, Deurne (Antwerp)© herinneringmemoire.be

Part of the Deurne police force entered the White Brigade resistance organisation after the round-ups of the Jews. Forty-three agents were deported, thirty-five of whom died in German concentration camps. After the war a number of the deceased agents’ names became street names and in 2017 a large remembrance monument was erected for the deported policemen. This immediately illustrates the fact that the history of the resistance is complex: diverse and contradictory. The post-war remembrance often fails to do justice to that history. One act of resistance has a prominent place, while another remains invisible to this day. From a broader perspective, there are different memories of the resistance on either side of the language border. But let us first examine the history of the resistance itself.

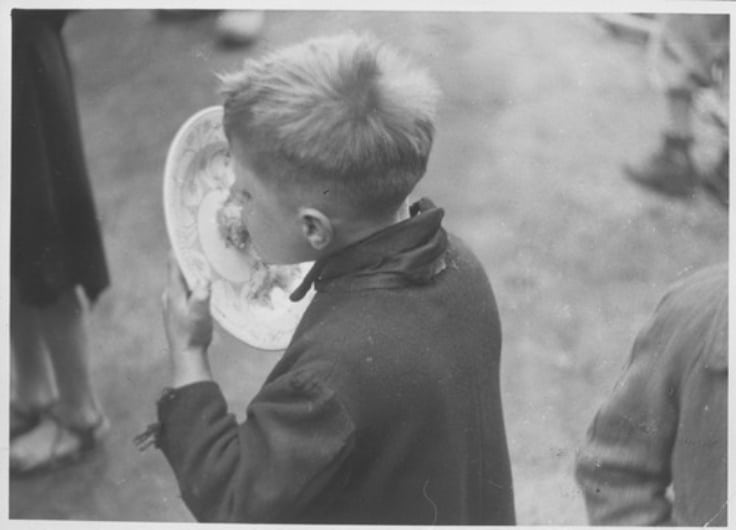

Members of the White Brigade

Members of the White Brigade© CegeSoma

A difficult start

As in the Netherlands and France, the context between May and September 1940 was not favourable for secretly organising resistance against the Germans. The war appeared to be over, collaborating with the new German rulers seemed best. In Belgium the German administration initially also behaved more moderately than the radical SS administration in the Netherlands. Belgium didn’t have state collaboration in the way Vichy France did. The fact that King Leopold III was present in occupied Belgium also led to confusion: many people waited for months to see if the head of state would play a role.

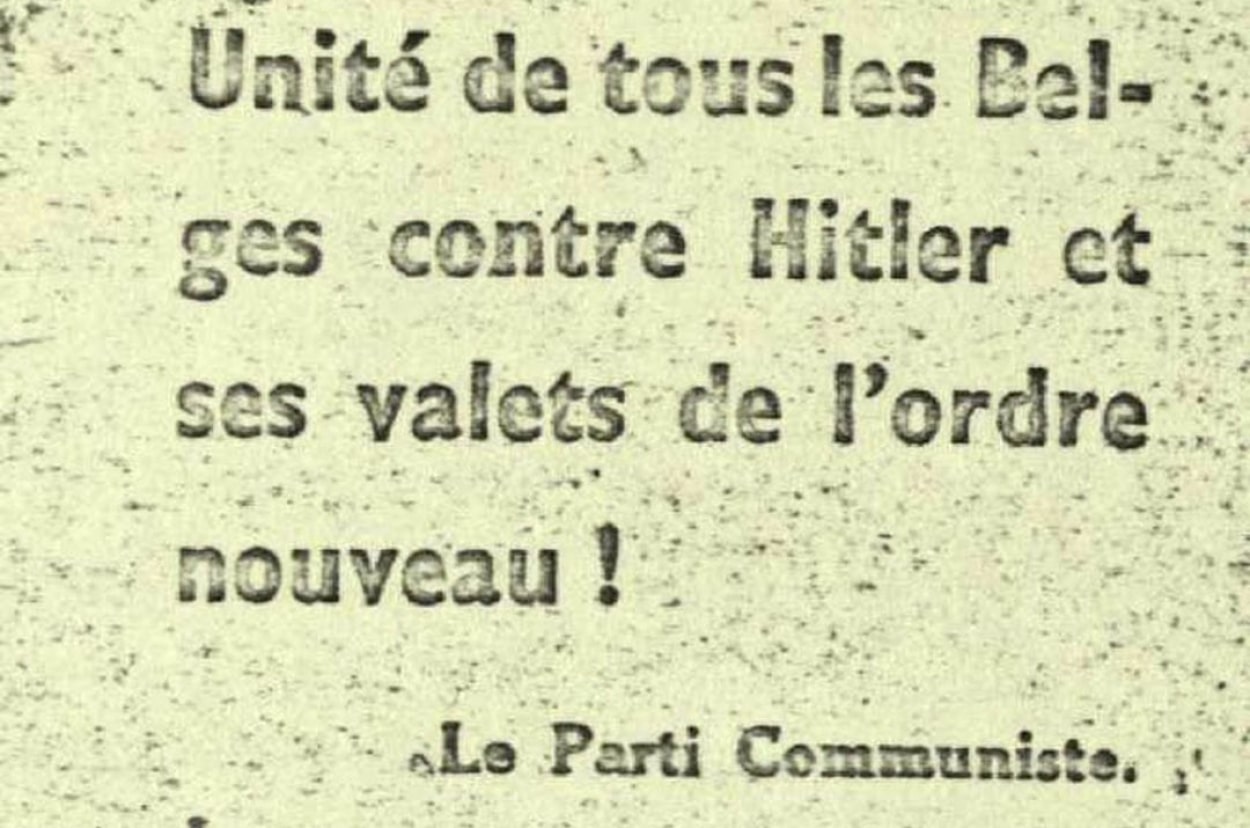

Message from the Communist Party calling for resistance

Message from the Communist Party calling for resistance© belgiumwwii.be

The organised underground resistance therefore took some time to get going. We find the first traces in the French-speaking middle classes, a social group that was active in the resistance in occupied Belgium during World War I and besides an active remembrance also retained its virulent anti-German sentiment and allied networks from that time.

The Communist Party of Belgium, with its anti-fascist DNA, was a second logical resistance environment, but its hands were tied by the non-aggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union (September 1939). Only the German invasion of the Soviet Union (June 1941) changed that so that the communists in Belgium, like the rest of Europe, under leadership of Moscow, could begin their resistance.

From September 1940 we see the first signs of change. Britain stood its ground, so the war wasn’t over after all. More people saw organised resistance as a feasible option. But it remained an exceptional choice for small groups of people. Germany and its allies continued to prevail on most fronts and committing acts of resistance was perilous. In January 1941 the first resistance fighter to be condemned to death in Belgium was executed. Caution was needed in finding reliable supporters, sound structures and a feasible approach.

Antwerp teacher Marcel Louette set up the White Brigade at the end of 1940.

Antwerp teacher Marcel Louette set up the White Brigade at the end of 1940.© belgiumwwii.be

So it’s not surprising that resistance almost always arose from structures and networks that already existed before the war. In 1940 and 1941 it was mainly a case of networks of people with the same socio-professional profiles. When the Antwerp teacher Marcel Louette set up the White Brigade at the end of 1940, he recruited primarily from the circles of the liberal youth movement he chaired and the school where he taught. Only from 1943 did his organisation penetrate further into other groups and regions. Another example was the Belgian Legion, founded in the autumn of 1940 and one of the earliest resistance organisations, which recruited exclusively among soldiers and was preparing to put the King in power if it became a possibility. From 1941 the Belgian Legion emerged as a resistance organisation.

It’s impossible to offer an overview of all organisations. From autumn 1941 two distinct groups emerged. Firstly there was the newly founded Independent Front that was established from the now clandestine Communist Party of Belgium but soon began to recruit in broader anti-fascist circles and also counted socialists, liberals and progressive Catholics among its ranks. The Independent Front grew to be a mass movement, but was particularly strong in Brussels and the industrial regions of Wallonia and weak in rural areas and in Flanders. It supported those in hiding or family members of arrested resistance fighters and also arranged the set-up and printing of around 150 clandestine newspapers. Besides the left-wing Independent Front there was also the Secret Army, stemming from the very right-wing Belgian Legion, one of the largest resistance organisations. The most important mission of the Secret Army was being ready to support the Allied forces militarily in the liberation.

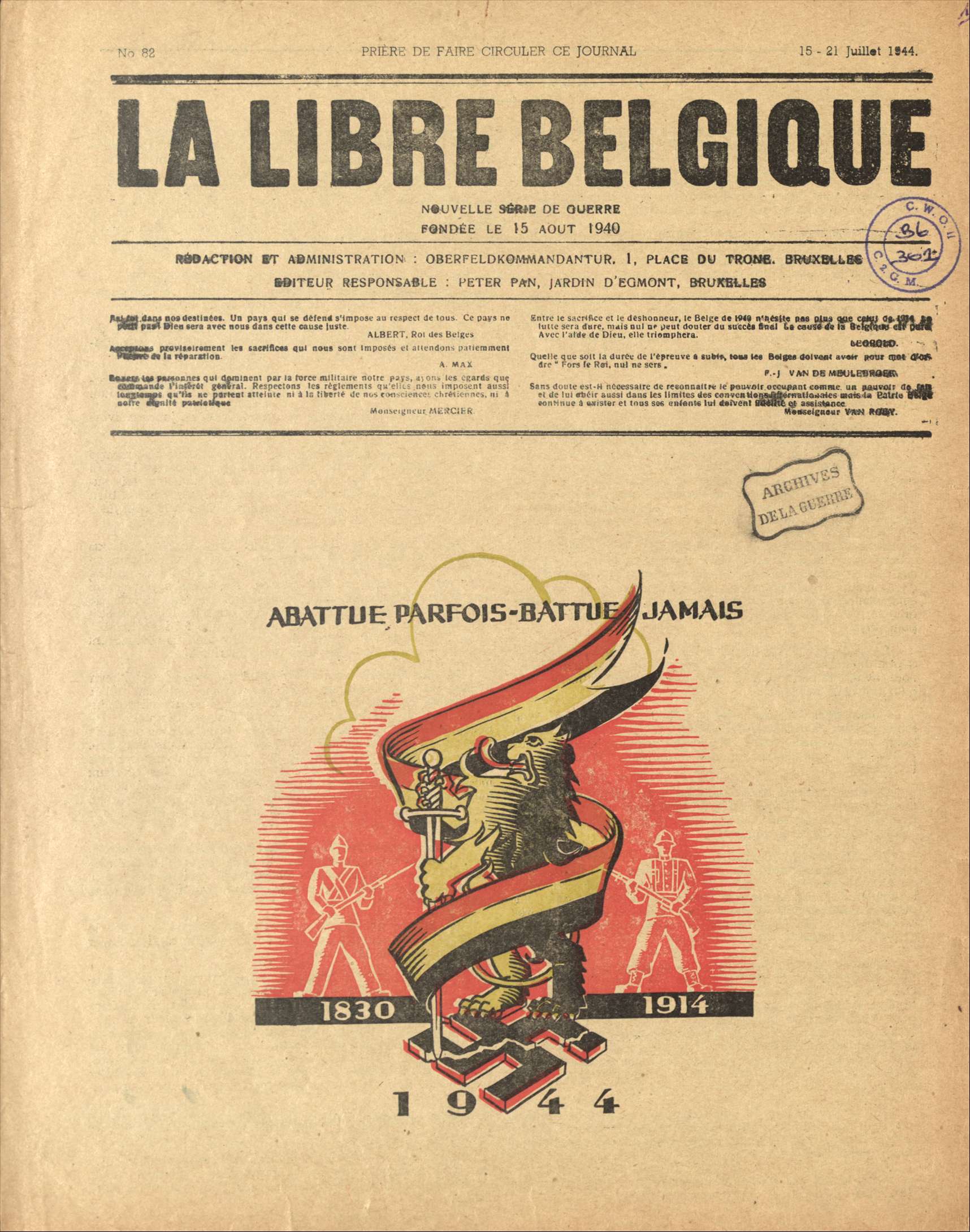

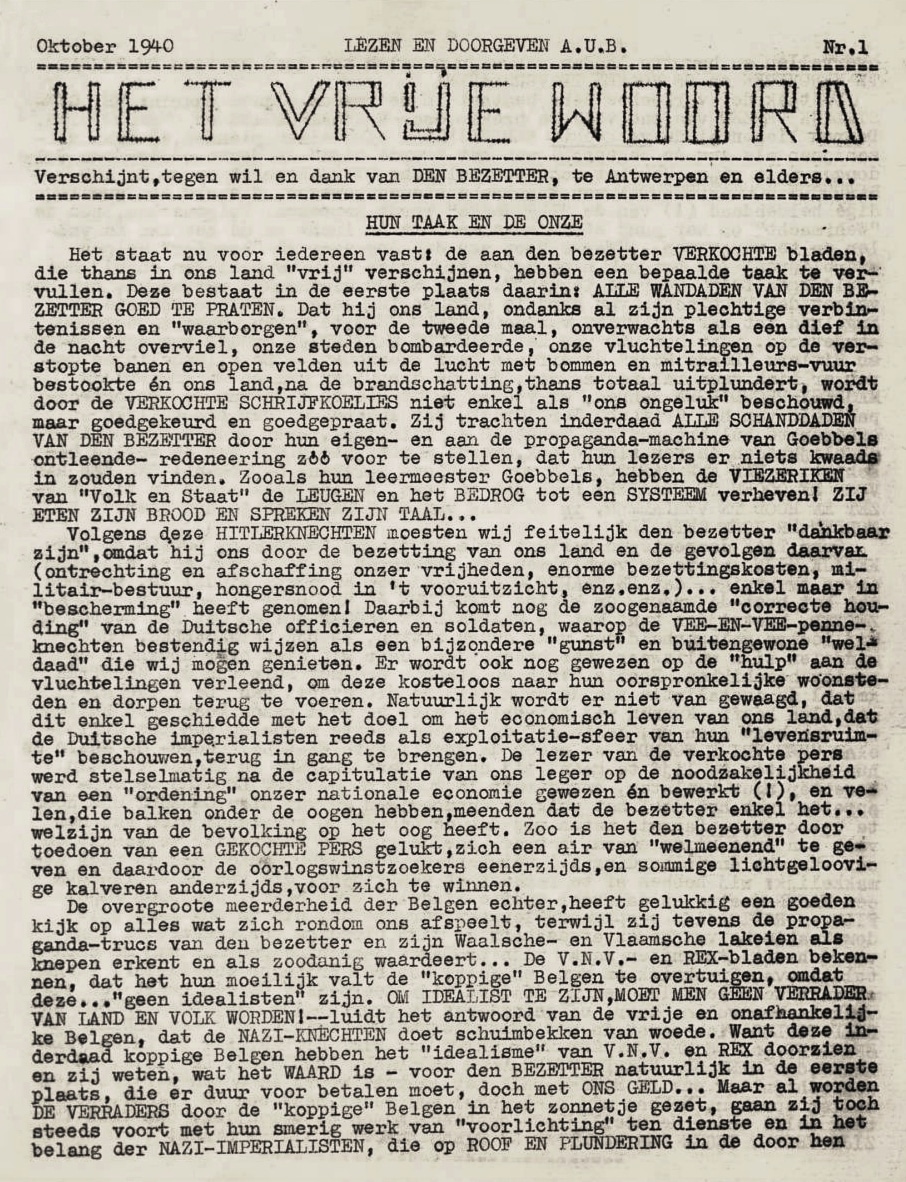

La Libre Belgique was one of the most important underground media. Het Vrije Woord was a Flemish underground publication,

La Libre Belgique was one of the most important underground media. Het Vrije Woord was a Flemish underground publication,© CegeSoma / Wikipedia

The division of the Belgian resistance into left-wing and right-wing blocks was in part a post-war analysis. The reality during the occupation was more complex. The resistance grew from the bottom up. National leadership was often absent. Dozens of small local resistance groups arose from pre-war structures, such as local sports clubs or youth movements.

In 1942 all over Belgium hundreds of small groups sprang up, mainly in large cities and in the industrial regions of Wallonia. They generally only became linked to national resistance organisations later in the war and sometimes even after it ended. They undertook concrete action with a handful of people from the district or village, or through a familiar, trusted organisation. Many people and groups also combined different forms of resistance: sabotage, intelligence work, clandestine press, support for those in hiding, administrative resistance and sometimes attacks. After the war various separate official resistance statutes were created, potentially giving the impression that this resistance activity happened separately in individual organisations.

A new phase after October 1942

The beginning of the Jewish deportations, with several large round-ups in the summer of 1942, did not lead to a substantial expansion of the resistance. However the Committee for the Defence of the Jews, which had links with the Independent Front, was founded at this point. Along with many ordinary citizens and religious organisations, this committee organised the rescue of thousands of Jews, including more than 2,000 children.

Hertz Jospa and his wife Have Groisman (Yvonne Jospa), founders of the Committee for the Defence of the Jews

Hertz Jospa and his wife Have Groisman (Yvonne Jospa), founders of the Committee for the Defence of the Jews© belgiumwwii.be

It’s not the persecution of the Jews but the introduction of compulsory employment in Germany on 8 October 1942 that led to the breakthrough in the resistance. Tens of thousands of families were affected and men went into hiding en masse, becoming dependent on help to survive in secrecy. This breakthrough moment coincided with changing fortunes in the war. The two battles of El Alamein (July 1942, October-November 1942), Stalingrad (early 1943) and the Allied invasion of Sicily (July 1943) made it clear that the Third Reich would not win the war.

Crest of the Independent Front

Crest of the Independent Front© Wikipedia

This signified an enormous boost to the resistance. Among other actions, the Independent Front now threw itself into organising help for those going into hiding, providing false papers and ration cards, material and financial support, in collaboration with the resistance group Socrates, an initiative of the Belgian government in London to support those refusing to work. As more and more people in hiding and resistance fighters were leaving the cities and the resistance networks formed increasingly long chains to remain in touch, rural regions were also integrated. But with the changing military fortunes, German repression also increased. There were large waves of arrests from summer 1942 until April 1943, and again from early 1944.

The Belgian government in London was long doubtful about the resistance. The government didn’t trust the communists or the royalist soldiers. Only in 1942 did the resistance gain support, and even then only gradually and not without difficulties such as internal tensions between military and government divisions, including the division for state security. The support from London only really got off the ground in 1943. Escape routes became more professional and there were various broadcasts from radio operators intended to help intelligence networks and offer material and financial support. In 1944 weapons and ammunition were also dropped.

Around 2.5% of the Belgian population aged 16-65 was involved in the resistance

More than 150,000 Belgians engaged in the resistance. No precise figure is available because post-war recognition procedures were not always reliable and many Belgians who effectively committed acts of resistance were not recognised. In any case the resistance was a matter for a small minority. Around 2.5% of the Belgian population aged 16-65 was involved. Around 40,000 resistance fighters were arrested, more than half of them in 1944. Almost 15,000 died in action, by execution or while imprisoned.

The Belgian resistance was pluralist but fragmented. An overarching national organisation never came together, during the war or afterwards. The types of resistance in Belgium didn’t differ fundamentally from those in other occupied countries. There were the intelligence services: in Belgium 37 networks were active with 18,716 officially recognised members. Secondly, there were escape routes for Belgians who wanted to defect to Britain, as well as English and escaped French soldiers, Jews, agents who had been ‘burned’ and Allied pilots who’d been shot down.

Photo of the clandestine printing house of "La Libre Belgique" in Liège, 1944

Photo of the clandestine printing house of "La Libre Belgique" in Liège, 1944© CegeSoma

In Belgium around 700 clandestine newspapers were published, giving Belgium the highest density in all of occupied Europe in this respect (after the liberation 12,132 Belgians were given the title ‘weerstander van de sluikpers’, or ‘underground press resistance member’). The majority of newspapers were centre-right oriented and three out of four of them were written in French, with a geographical concentration in Brussels and Liège. The most inspiring was the armed resistance (in total around 140,000 known members).

The most important organisations were the Secret Army, mentioned above, and the Armed Partisans. By June 1944 the Secret Army had around 54,000 members, supported by a military cadre but recruiting from all levels of society, albeit notably less from the working classes.

© CegeSoma

The right-wing conservative organisation also expanded significantly in Flanders from 1942 onwards. From summer 1943 it received material and financial support from London. The Armed Partisans was founded after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 out of the Communist Party of Belgium. At first they committed small acts of sabotage, but from spring 1942 they also began to assassinate collaborators. A majority of the approximately 850 attacks on individuals in Belgium were committed by the Armed Partisans. The impact of the group, given its relatively limited support, was significant.

Besides this large national organisation there were dozens of specific groups focused on specific areas. The Syndicale Strijdcomités (founded in early 1942), for example, combined social struggle for better working conditions with the fight against the occupier (and at the same time with out-competing socialist trade unions). The sabotage group Groupe G – which arose from the ideological anti-fascist environment of the Université Libre de Bruxelles – consisted of technically trained people who sabotage the rail- and waterways and the energy supply, mainly from 1943 onwards.

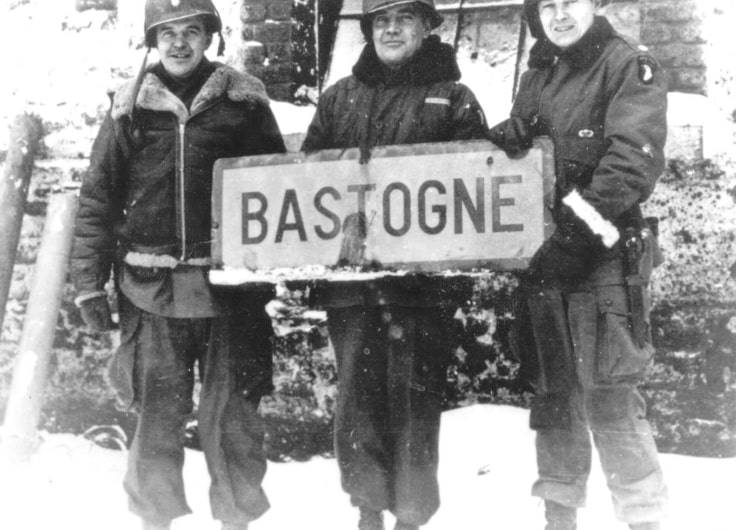

Urbain Reniers (centre), head of the coordinating committee of the resistance during the liberation of Antwerp

Urbain Reniers (centre), head of the coordinating committee of the resistance during the liberation of Antwerp© CegeSoma

After the war: forgotten resistance

The resistance didn’t become anchored in the Belgian collective memory, in contrast with that of its neighbours, France and the Netherlands. The political and moral legacy of the resistance has even been largely forgotten. There are various reasons for this. Firstly the resistance is not linked to the traditional Belgian elites. The remembrance of the war arose from the bottom up and in retrospect that has worked out to the disadvantage of the resistance. Memory of the resistance, after all, is fused with the strong remembrance culture established after World War I. That had a predominantly military and ritual tradition that quickly gives the memory of the resistance a rather dated feel and misses connections with the more modern messages of peace and human rights that might appeal to younger generations.

Secondly, there was the internal division already mentioned between left-wing and right-wing factions which already arose immediately after the liberation. The state did not create a national remembrance. The competition for recognition and the controversial role of King Leopold III (the Royal Question) widened the rifts in a single national resistance community.

September 1979: a member of the gay rights movement distributes pamphlets in the concentration camp of Breendonk (Flanders), but is ignored by a veteran. The photo symbolises how, in the 1970s, part of the traditional patriotic movement in Belgium failed to reach out to young people and new social movements.

September 1979: a member of the gay rights movement distributes pamphlets in the concentration camp of Breendonk (Flanders), but is ignored by a veteran. The photo symbolises how, in the 1970s, part of the traditional patriotic movement in Belgium failed to reach out to young people and new social movements.© Kr. De Munter

After the battle between left and right, there was opposition between Flanders and French-speaking Belgium, which can be traced back to the significantly weaker implantation of the resistance in Flanders. Approximately 42.5% of resistance fighters came from Wallonia, 31.5% from Brussels and just 25.5% from Flanders. This came down to a combination of factors. Left-wing anti-fascism was not as politically strong in Flanders. On Hitler’s orders the occupying forces were pro-Flemish in their policies, for instance freeing Flemish prisoners of war and deriving political power from anti-Belgian Flemish nationalism. Belgian patriotism was not as strong in Flanders, in part also as a result of Flemish language demands not being granted after World War I.

Approximately 42.5% of resistance fighters came from Wallonia, 31.5% from Brussels and just 25.5% from Flanders

Flemish nationalism had considerable support (in 1939 around 15% of the electorate in Flanders) and it maintained close connections with the pro-Flemish wing of the Catholic Party. As Flanders and French-speaking Belgium continued to grow apart in the 1960s, this was the deathblow to a resistance remembrance that maintained the idea of an indivisible, unitary Belgium. In Flanders the remembrance of the resistance was thus entirely consigned to oblivion.

The weak remembrance of the resistance also made it easy to minimise the real significance of the movement. Nevertheless the Belgian resistance was an impressive achievement. Particularly important were the many thousands of documents supplied to Britain, the thousands of men and women they enabled to escape from occupied Belgium and the humanitarian aid that went to tens of thousands of Belgians in hiding and their families, as well as to Russian and Polish prisoners and persecuted Jews.

The Belgian resistance was an impressive achievement

From a military perspective, there were acts of sabotage (100-250 acts per month from September 1943 to May 1944, and 400-600 per month from June to August 1944). The help with the liberation itself was more limited, as it happened unexpectedly quickly, but there was still important operational support in the liberation of the port of Antwerp, essential to Allied supplies from November 1944. The attacks and especially the strong distribution of clandestine press undoubtedly had an effect in deterring the population from supporting the Germans and the collaboration. This is an important track record that deserves a more prominent place in the Belgian memory of the war.