Why the Dutch Often Have Difficulty With Authority

Is there such a thing as a ‘Dutch identity’? And if so, what does it look like? Jan Renkema provides a clear analysis of the main characteristics in his pamphlet ‘The DNA of the Netherlands’. This week he explains why the Dutch love their independence and freedom.

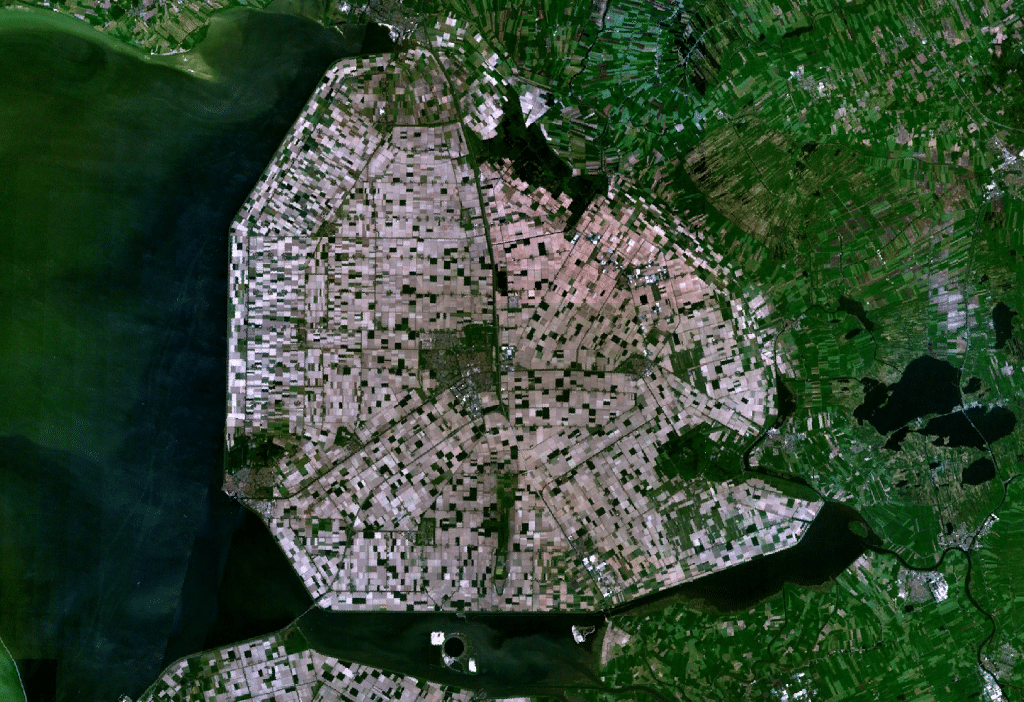

Right now, the clouds are stopping us from seeing anything outside. This is the perfect time for a brief historical overview. The low land in and around the river delta proved to be fertile. In the struggle against the water, we learned how to extract land from the sea. Land reclamation proved to be very successful; first in the Middle Ages by the monks in Groningen and Friesland, then the polders in Holland from the sixteenth century, and the IJsselmeer polders in the twentieth century. The Dutch landscape, the landschap, is largely man-made. Schap comes from the verb scheppen, ‘to create’. This idea of ‘creating’ brings to mind our national tools: shovels and paddles.

The Dutch are specialised in extracting land from the sea. This satellite image shows land reclamation of the Noordoostpolder, part of the Flevopolder.

The Dutch are specialised in extracting land from the sea. This satellite image shows land reclamation of the Noordoostpolder, part of the Flevopolder.© NASA

The myth about the origin of the Netherlands did not just appear from thin air. The seventeenth-century French philosopher and mathematician Descartes, who in fact wrote some of his most important works while staying in the hospitable Low Countries, wrote “God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands”. The Dutch are always kept busy with the landscape, always changing it, for example relocating an old tree if it must otherwise be cut down to make way for a new metro line. Even today, people are still busy replacing structures that are hardly in need of replacement. Land reclamation continues even in this century. A new peninsula is now emerging off the coast of the Hook of Holland, thanks to our smart dredging technology, using sand from beneath the sea and aided by tidal currents. The Netherlands is still regarded as being particularly resourceful in this area. It is no coincidence that our King specialised in water management during his training for kingship.

Aerial view of the fortified city of Naarden, one the many water-based defenses that are part of the Holland Water Line. This defense line was built to withstand intruders.

Aerial view of the fortified city of Naarden, one the many water-based defenses that are part of the Holland Water Line. This defense line was built to withstand intruders.The small community here could stand their ground because they became so good at water management, in dredging and dyke construction, in building large waterworks with locks. That certainly did not go unnoticed by the great powers all around us. They saw us as a potential haven for taxation or supplier of soldiers, or wanted to earn money by means of international trade through our rivers and ports. First Spain, then France, Prussia and England, and much later, Germany. All of these attacks could be repelled. We were actually helped by the water in this way. When intruders threatened, we temporarily flooded land as a line of defence so that the enemy could not continue. We like to think that we have always fought bravely for our independence. Our national symbol is the Dutch Lion for a reason. But were we really that strong? Perhaps not. Maybe we were only able to make it through with the support of our attackers’ enemies, because none of the great powers around us could allow another to take control of this promising river delta and its rich potential.

Venting one’s own opinion about everything is considered relatively normal behaviour in the Netherlands

There is, of course, another side to our independence. All that struggling against the water and foreign interference also stimulated a certain perpetuation of the Dutch ‘cheese head’ stereotype. Noisily making our presence known in a restaurant and venting one’s own opinion about everything is considered relatively normal behaviour in the Netherlands. Our direct manner can sometimes seem blunt and impolite. And if we disagree, we just split off into smaller groups. After all, we are already used to living on small ‘islands’. Our independence often manifests itself in the free-spirited mindset of ‘I’ll decide for myself’.

We often have difficulty with authority. We Dutch are also rarely enthusiastic about uniforms. You wouldn’t think so because of our desire for equality, but in such a densely populated country, you must be able to distinguish yourself from others. School uniforms are therefore not part of Dutch culture. The uniforms of authority figures are often seen as unavoidable but necessary manifestations of bureaucracy.

The Dutch often have difficulty with authority.

The Dutch often have difficulty with authority.© Marshallmuseum.nl

Our freedom-loving nature often manifests itself in an anti-hierarchical attitude. Let me give you some examples. On some motorways, the maximum speed can change from 100 to 120 to 130 km/h, and different limits apply in the evening. Speed checks are announced over the state-sponsored radio. But such bureaucracy evokes remarkable opposing forces. If the government places speed cameras on regional roads, then at night rural youths, with tacit permission from their parents, will ram into them with loaders. Then the speed cameras – which cost € 30,000 and include a rotating camera – are skewed so that the camera ends up only photographing grass.

Here’s a more subtle example to conclude with, now that we have landed. In other cultures you might help someone without being asked, just to be nice. But if you were to give a fellow Dutch passenger a hand to wriggle a heavy suitcase out of the luggage rack, the chances are that you would be met with a very strange look. A curt ‘thank you’ would likely be all that follows, since after all they got it up there in the first place. We Dutch like to fend for ourselves, for fear of further interference.

Ah, it looks like we’ll still be taxiing for a while toward the arrivals hall. This gives us a good segue toward the seventh and final characteristic: our livelihood, our transit economy.