Why Vondel Looked Like A Fisherman in Harem Trousers

Harem pants have been a staple of summer fashion these past few years. In the Low Countries, they are sold under the name ‘harembroek’, but they used to be commonly known as ‘Turkse’ or ‘pofbroek’ or, curiously, ‘haringbroek’, herring trousers. The famous Dutch poet Vondel apparently wore them, as did ladies of the sporting type and people who moved to New York. This is the story of a confusion of tongues.

In the Dutch language, bloomers have been known under a variety of names. ‘Pofbroek’ simply describes its shape. The now popular ‘harem’ reminds wearers of the Near and Middle East, where this type of trousers, wide in the middle but narrow at the knee or ankle, forms part of ordinary everyday dress.[1] While working on a translation of an historical novel set in late-nineteenth-century Amsterdam, however, I came across a third appellation. It comes up in the following dialogue between two children about national poet Joost van den Vondel:

‘Vondel and his friends were dressed a little like our fishermen from the island of Marken.’

– ‘You’re kidding! In herring trousers?’

– ‘Yes, in herring trousers.’ [2]

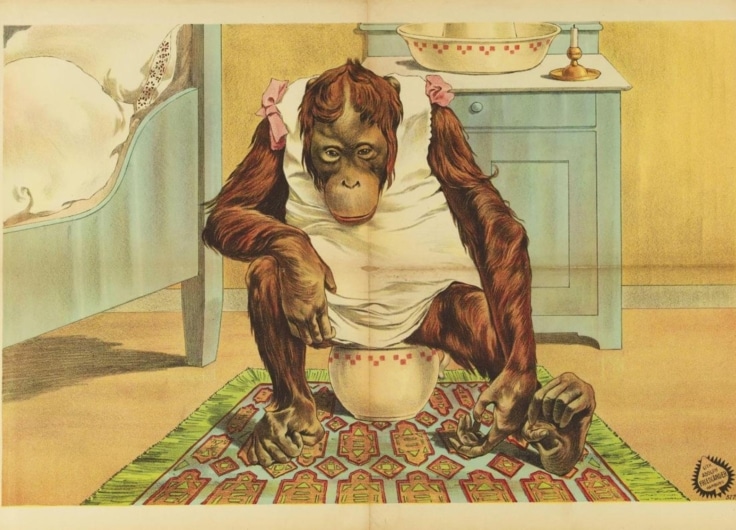

Vondel in harem trousers like a fisherman (W. P. Hoevenaar and P. W. van de Weijer, ‘Joost van den Vondel’, in J. van Lennep, Neêrlands Roem, Utrecht: Bosch, 1868)

Vondel in harem trousers like a fisherman (W. P. Hoevenaar and P. W. van de Weijer, ‘Joost van den Vondel’, in J. van Lennep, Neêrlands Roem, Utrecht: Bosch, 1868)© www.gutenberg.org

I have not been able to find these ‘herring trousers’ in any of the relevant historical dictionaries.[3] But the seventeenth-century Vondel evidently wore puff breeches. Does this mean that ‘herring’ is simply one child’s comic misunderstanding of the word ‘harem’, as they sound so similar in Dutch? I suspect more is going on here.

Exotic fashions

In the early eighteenth century, European high society was bewitched by all things oriental. You can see this in paintings, in stories, and in the fashion for so-called Turkish trousers, worn by ladies at a time when it was only men who were expected to ‘wear the trousers’. Turkish trousers received a new boost in the mid-nineteenth century when dress reformer Amelia Bloomer popularised the comfortable ‘Bloomer Costume’. In the late nineteenth century, puffed trousers, and trousers in general, experienced their definitive breakthrough with a European female clientele, first as daring sportswear, worn by cycling ladies for instance, and then in high fashion.[4]

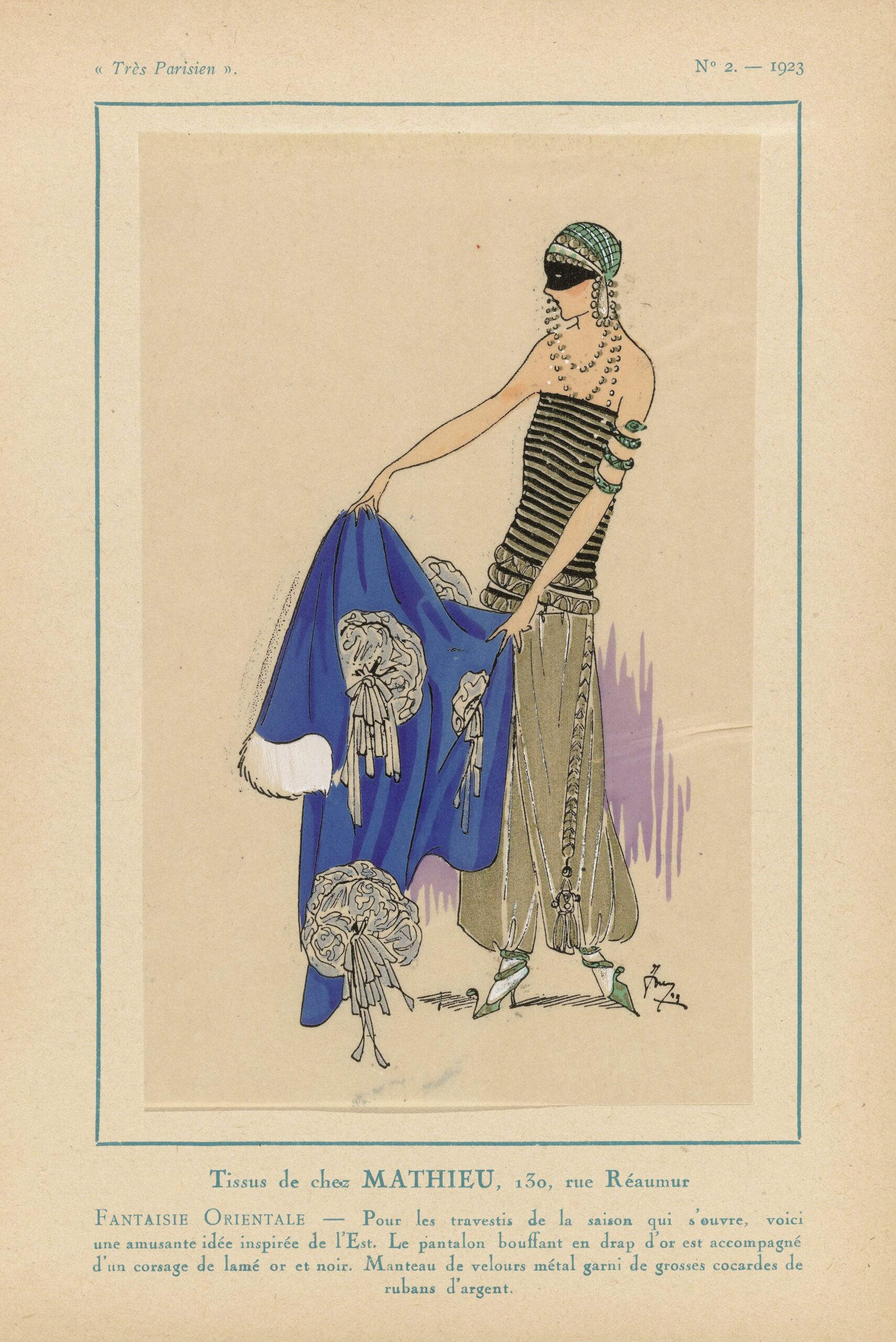

The orientalist fantasies of European consumers (D. L. Mathieu and G. P. Joumard, ‘Tissus de chez Mathieu [...] Fantaisie Orientale’, Très Parisien 2, 1923)

The orientalist fantasies of European consumers (D. L. Mathieu and G. P. Joumard, ‘Tissus de chez Mathieu [...] Fantaisie Orientale’, Très Parisien 2, 1923)© Rijksmuseum

In Dutch, the common designation for this item of clothing had for centuries been ‘Turkse broek’, trousers with ‘poffen’, or, from around 1900, ‘pofbroek’. The ‘harembroek’ does not feature in the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal until after WW II, but in Dutch literature, the word ‘harembroek’ does start cropping up in the 1910s to 1930s, which was a period of intense fascination with Egypt and other ‘oriental’ places. In these years, the earlier association of the trousers with the Turkish Empire generally, apparently shifted to the harem: a specific image of a sexualised space populated by women. The literary ‘harem’ pants then went underground for a few decades, only to surface again abundantly in the 1990s. (The ‘pofbroek’ had never disappeared from the scene.)[5]

It is possible that the children’s dialogue, set around 1880 but written in the Interbellum, is really a retrospective projection. That is, the author Neel Doff may have applied a term which was in vogue while writing her book, forgetting that the children of her youth did not yet learn the word ‘harembroek’. On the other hand, my Dutch dictionary does not record spoken language, let alone the kind of language spoken in the slums of Amsterdam. And the Oxford English Dictionary does mention ‘harem pants’ for the late nineteenth century. What’s more, Doff’s novel is largely based on her own memories. Also, her reference to herring is not actually that far-fetched.

Zuiderzee communities

Not only ‘Turkish’ trousers but also the more neutral ‘pofbroek’ was often associated with Mediterranean and Middle Eastern cultures, in Dutch literature. Yet intriguingly, the same term was used for fisherman’s clothes. From the 1890s onwards, in particular, writers liked to mention ‘pofbroeken’ when describing the men living and working around the Zuiderzee.[6]

In fact, the association between the trouser model and certain Dutch communities was so strong that the early Dutch settlers in what is now New York, the Knickerbockers, named after the fictional Mr Knickerbocker, lent their name to the American knickerbocker, and thence to the underwear: ‘knickers’.[7]

(The Dutch thus becoming the Turks of America.)

Fisherman on another Zuiderzee island (Harry Bedijs/Anefo, ‘Urker visser aan het hoekwant spleten’, 1946) & Dutch fisherman on Marken (1890-1905)

Fisherman on another Zuiderzee island (Harry Bedijs/Anefo, ‘Urker visser aan het hoekwant spleten’, 1946) & Dutch fisherman on Marken (1890-1905)© National Achives, The Hague / © Library of Congress, Washington

And so, returning to the Low Countries: for most readers of Dutch literature at the turn of the twentieth century, bloomers thus represented either of two exotic locations: the quaint, ‘traditional’ fisher communities around the Zuiderzee; or the sensuous, mysterious world they dreamed up around Muslim women.

Seeing that the trousers worn by Vondel had by the late nineteenth century likely already come to be referred to as ‘harem trousers’, and seeing that there were two picturebook places where a working girl from Amsterdam would have seen such trousers – the East and the Zuiderzee – it is no longer altogether surprising to find the famous poet dressed in herring trousers.[8] The older tradition of baggy trousers[9] which lived on in nineteenth-century fishing villages, thus continued to interfere with the fashions which the European beau monde gleaned from the East.

Sources

- M. J. Brusse, ‘Uit mijn notitie-boekje’, Alkmaarsche Courant (17 August 1940), 7.

- Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren, www.dbnl.org.

- Neel Doff, Keetje trottin (Bruxelles: Labor, 1999), 43.

- Marjorie Garber, Vested Interests (New York: Routledge, 1992), 311-16.

- Madelief Hohé and Ileen Montijn, Romantische mode (Zwolle: Waanders, 2014), 137.

- Modemuze, www.modemuze.nl.

- Oxford English Dictionary, www.oed.com.

- L., ‘Onder-Onsjes’, Schuitemakers Purmerender Courant (8 March 1916), 2.

- Trésor de la Langue Française informatisé, www.cnrtl.fr/definition.

- Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, gtb.inl.nl.