Why We Should Not Forget the Berbice Slave Revolt of 1763

Thanks to the National Archives of the Netherlands, for the first time we can read the letters of the leader of the first-ever large-scale organised revolt of enslaved people in the Americas. And that is quite an event, Professor Salverda of University College London believes. ‘The significance of the Berbice slave revolt goes way beyond the Netherlands.’

The small exhibition Rebellion & Freedom in the National Archives in The Hague showcases the history of three uprisings and their impact on Dutch society in the past and present. On display are three historical documents of the first order.

To begin with, there is the declaration of 1588 with which the Dutch proclaimed their freedom and independence from the Spanish King Philips II. Then, from 1795, there is the Batavian Republic’s first Constitution, adopting the principles of the French Revolution, together with a printed request, signed by two hundred Dutch women, demanding equal rights as citizens under this Constitution.

The exhibition’s centrepiece dates from 1763 and documents the first-ever mass revolt in the history of the Americas, which broke out in February 1763 amongst the black slaves in the then Dutch colony of Berbice (now Guyana, near Surinam).

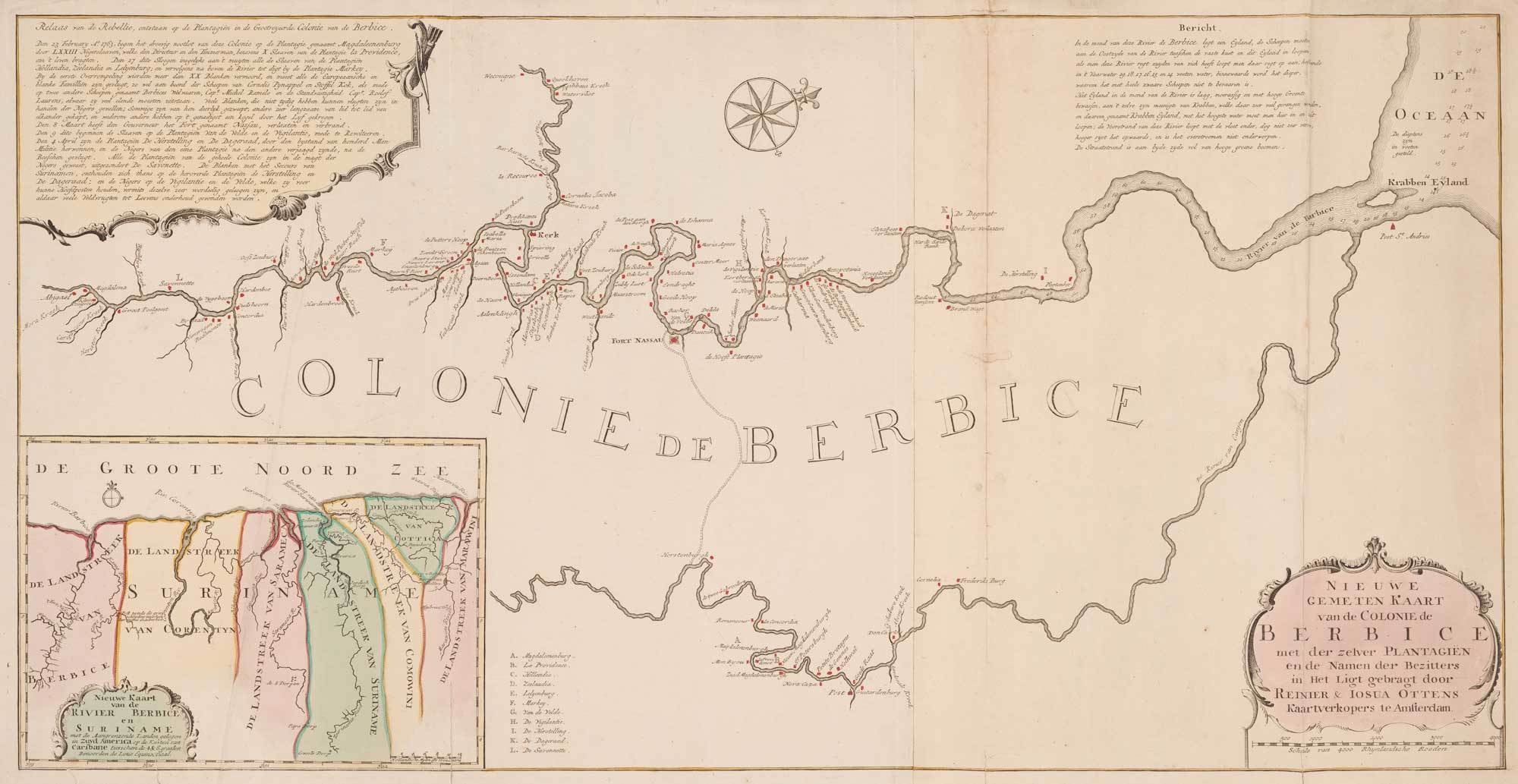

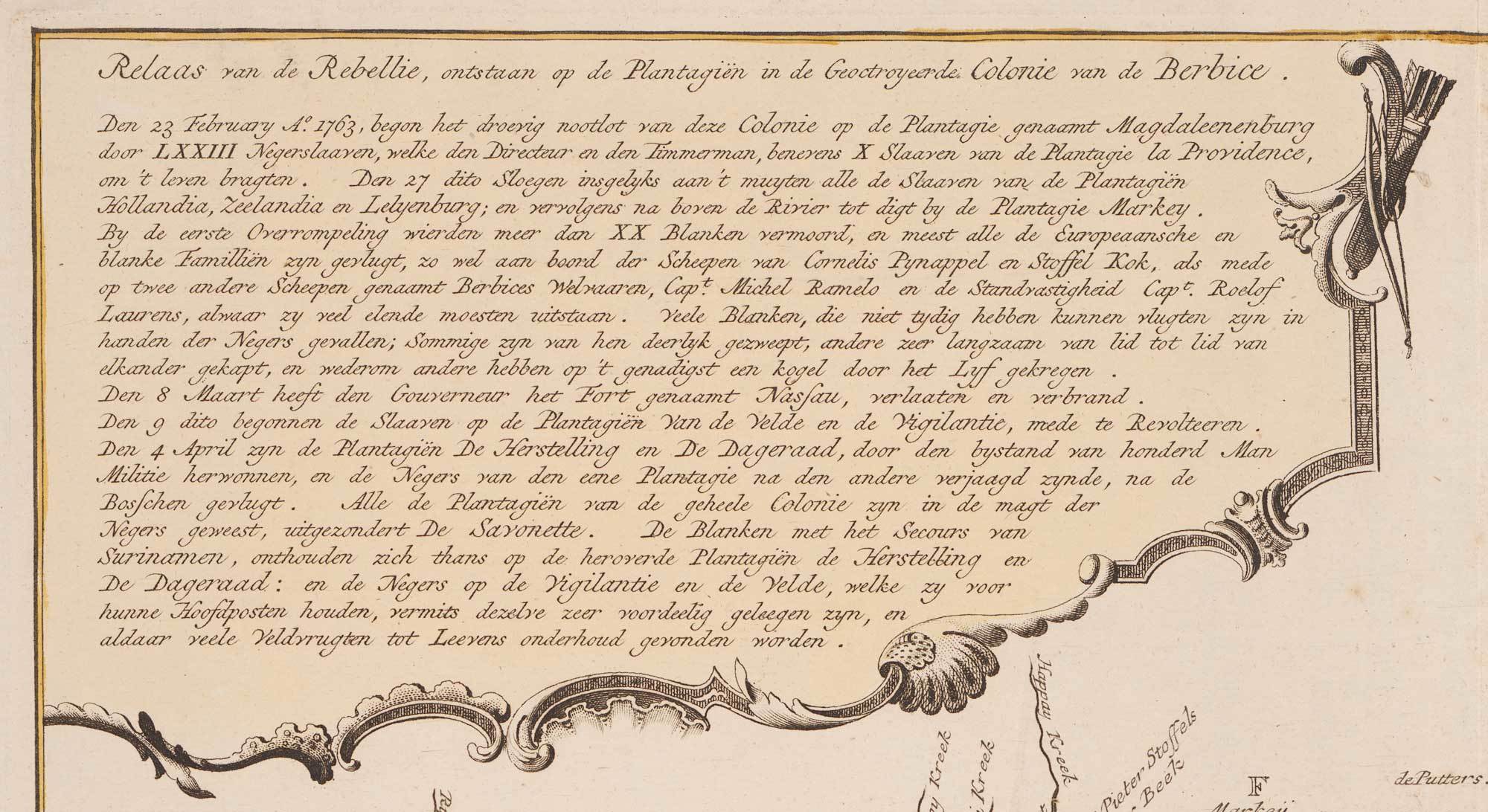

Map of the Berbice colony, with a story in cartouche about the slave uprising of 1763. Engraving published by Reinier and Josua Ottens in September 1763

Map of the Berbice colony, with a story in cartouche about the slave uprising of 1763. Engraving published by Reinier and Josua Ottens in September 1763© Zeeland Archives

On display are the letters written by Coffy, the leader of the Berbice Slave Revolt, to the Dutch governor, who had fled to safety on board his ship. What Coffy proposed in these letters was that the two sides should negotiate and agree to peaceful coexistence in Berbice of the free Blacks with their former Dutch masters.

What actually happened was a very violent suppression by the Dutch of this revolt. Those were the days when the Dutch were known the world over for the unheard-of cruelties they perpetrated against their slaves in Surinam – decried in Voltaire’s Candide

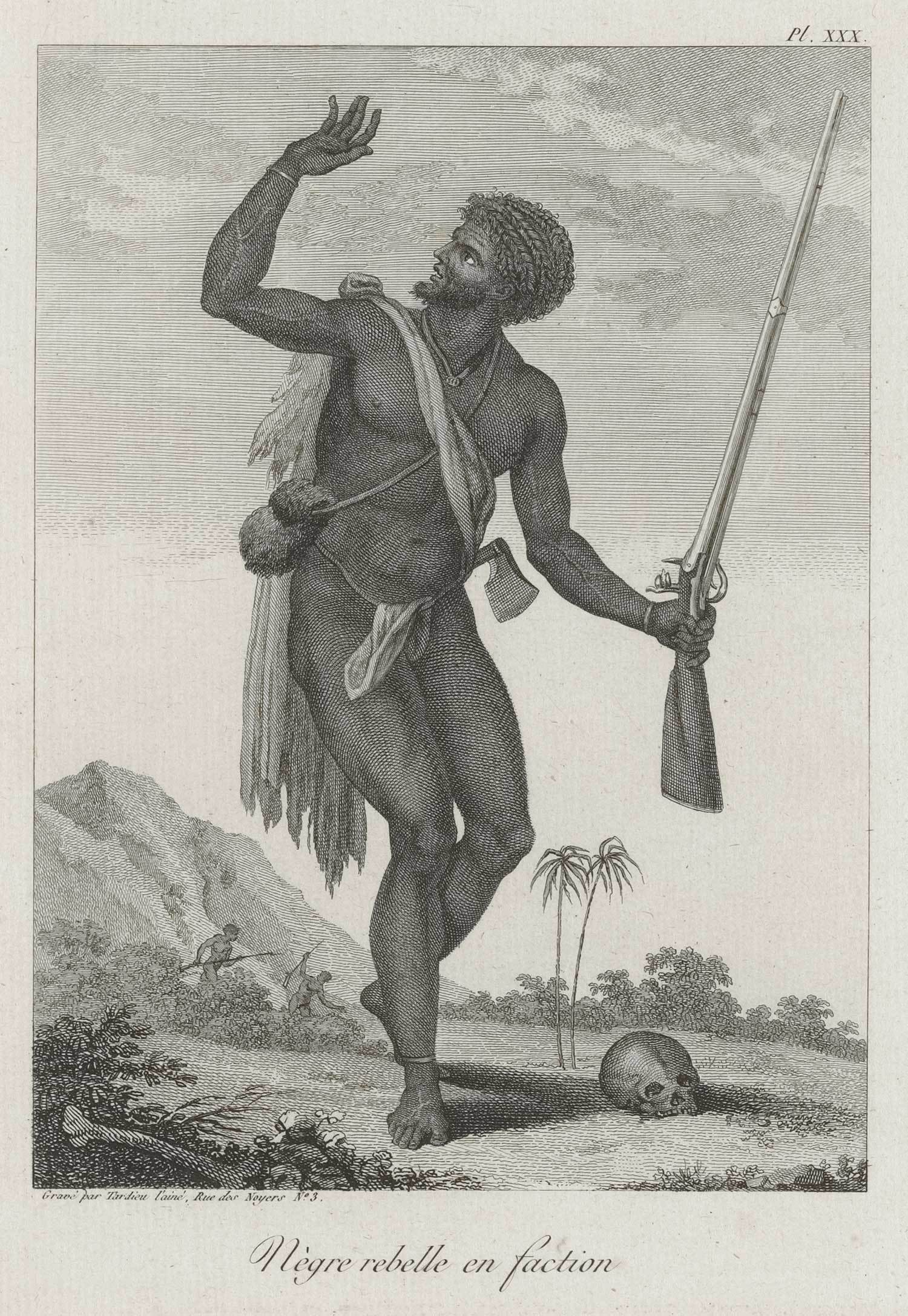

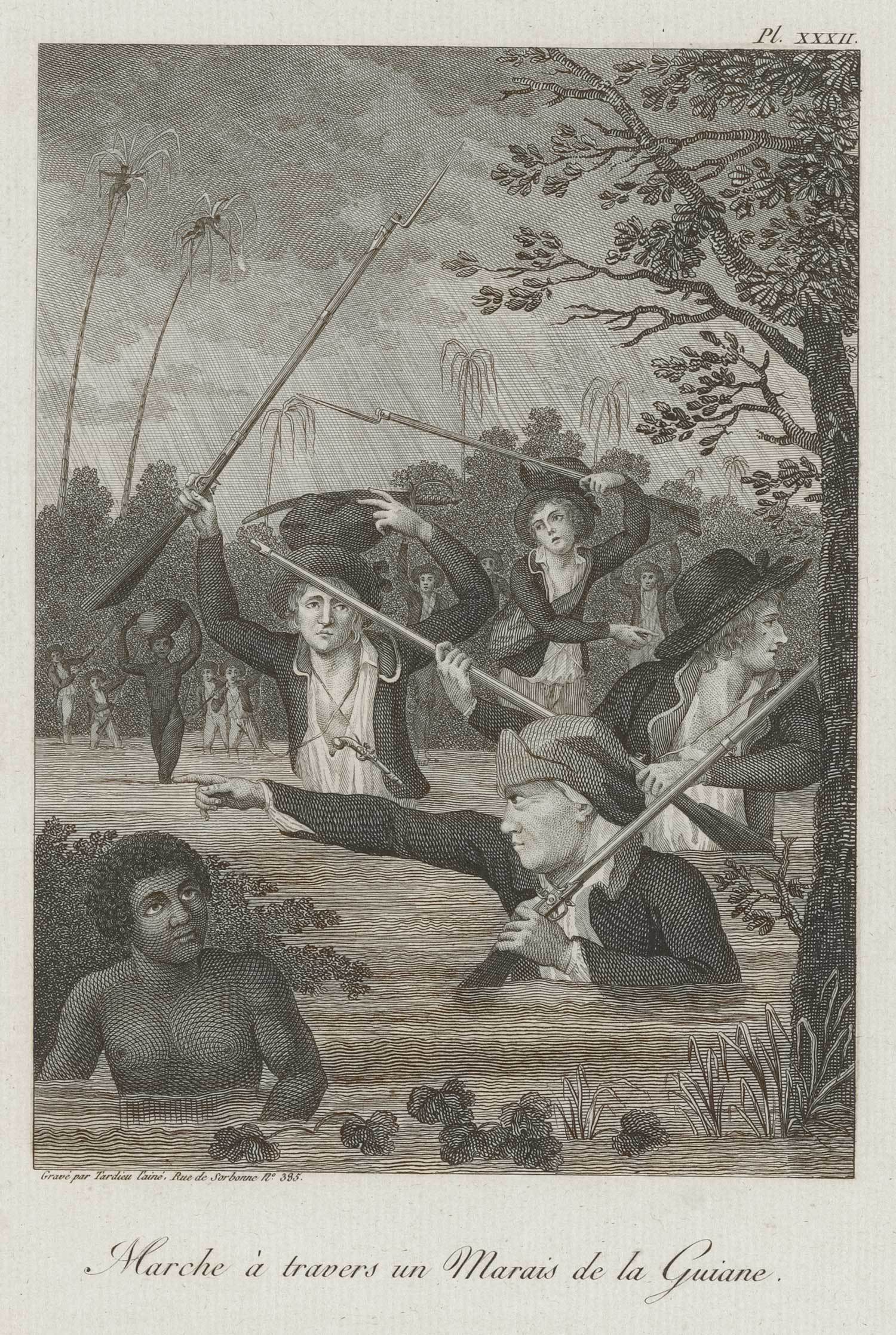

(1759), in the Abbé Raynal’s famous Histoire des deux Indes (1774), the colonial complement to Diderot’s Encyclopédie, and in Stedman’ Narrative of Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796) with its gruesome illustrations by William Blake.

Rebelling enslaved African/March of the soldiers in the marshes of Surinam. Engravings based on the drawings of J.G. Stedman and pictures of William Blake by Tardieu L’Ainé, in: ‘Voyage a Surinam […]’, Paris 1799

Rebelling enslaved African/March of the soldiers in the marshes of Surinam. Engravings based on the drawings of J.G. Stedman and pictures of William Blake by Tardieu L’Ainé, in: ‘Voyage a Surinam […]’, Paris 1799© Zeeland Archives

Almost incredibly, Coffy’s letters have survived in the National Archives. And thanks to this extraordinary find we can now, for the first time, read his own words.

The significance of this goes way beyond the Netherlands. The Berbice Slave Revolt of 1763 was directly connected to great world events. It was an all-time first in the history of the Americas – a full three years before the American Revolution of 1766; and twenty-eight before the great slave revolt of 1791 under Toussaint l’Ouverture, which led to freedom and the independent state of Haiti.

As Coffy’s contemporary, the Abbé Raynal, wrote in his Histoire des deux Indes: the Berbice Slave Revolt nearly had a devastating impact for all of the Americas. The black slaves, though defeated, had not been extinguished, and the seeds of liberation had been sown. And as Raynal prophesied: one day, a strong black head, a Black Spartacus, would come, to avenge his nation, so barbarously treated by their Dutch masters.

Story of the slave uprising on a map of Berbice

Story of the slave uprising on a map of Berbice© Zeeland Archives

In Haiti, Toussaint l’Ouverture had Raynal’s book in his library, and in 1796, when he victoriously entered the capital, he was presented to his people as ‘the Black Spartacus announced by Raynal’.

Long before that, the fight for freedom had begun. Today, the usual date for commemorating the end of slavery in the Dutch colonial empire may be 1863. But, as this exhibition makes clear, the Berbice Slave Revolt took place a full century before that. And Coffy led the way.