Why You Can Speak Your Mind in the Netherlands

Is there such a thing as a ‘Dutch identity’? And if so, what does it look like? Jan Renkema provides a clear analysis of the main characteristics in his pamphlet ‘The DNA of the Netherlands’. This week he explains why togetherness is a core principle in that land lower than water.

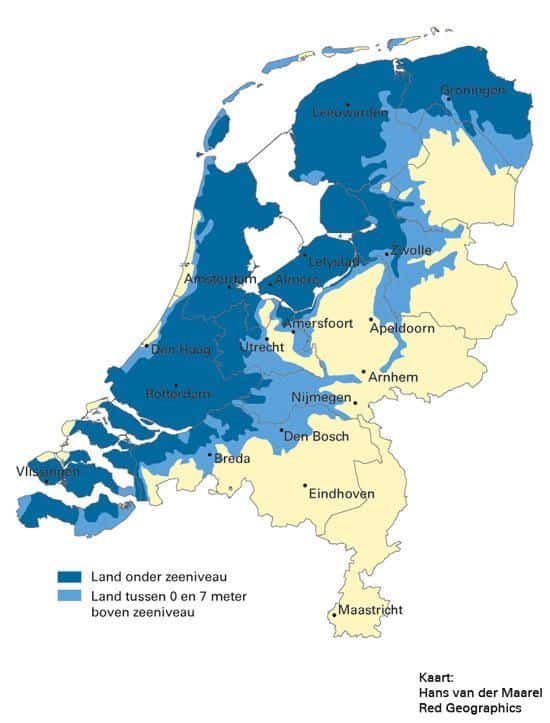

The Netherlands is largely below sea level and is even lower than the rivers that flow through it. This means we depend on each other to keep our feet dry and our farmland fertile. If one town does not maintain its dykes well enough, the next will be flooded. If my neighbour neglects to build enough windmills, his water will flood my lower-lying polder land. We all know that we cannot continue to live here without working together to protect our hard-won acquisitions against the ever-rising water. It’s no coincidence that the Netherlands is the only country in the world to have a separate water board tax.

The dark blue indicates land that is below sea level.

The dark blue indicates land that is below sea level.© Red Geographics

In the constant struggle against water, we need always to consider and consult one another, whether we like it or not. To quote our own Johan Cruijff, the best footballer of all time, “Water has nothing to gain from us, and yet we have everything to lose to it – if we do not cooperate.” This explains why there is a particular culture of mutual consideration in these Low Countries, where everyone can speak their mind. The Netherlands has something unique in this way: the polder model. It is a system with substantial government intervention, and which involves many long discussions, with a constant willingness to compromise and whose aim above all is a general consensus.

The Dutch polder model involves many long discussions, with a constant willingness to compromise and whose aim above all is a general consensus.

The Dutch polder model involves many long discussions, with a constant willingness to compromise and whose aim above all is a general consensus.© NPO Radio 1

Because of the dykes and windmills, we are used to the need for mutual protection by means of communal facilities and the necessity of standing up for those in weaker positions. We could all find ourselves in need of help when the country is flooded, or for some other reason. In the Netherlands, half of every euro earned is spent under the auspices of the government. We have a relatively high minimum wage, and one of the best pension provisions in the world. Government disability support is also very well organised. What is more, we are always very generous with charity campaigns. Sometimes, we have evening-long national TV specials hosted by Dutch celebrities to encourage people to donate, while trying to reach a new fundraising record. The Dutch live peacefully and are inclined toward an idea of overall harmony. In its own capacity, the Netherlands is also working on projects in pursuit of international peace.

In the Netherlands, there is a constant structure of discussion, which allows everybody to have their say

In the Netherlands, there is a constant structure of discussion, which allows everybody to have their say. Take, for example, large traffic projects such as the Betuwelijn railway from Rotterdam to Germany, the new North-South metro line in Amsterdam, or the renovation of the Rijksmuseum. They were all very slow projects because all parties had to be consulted, including the cyclists who were accustomed to using an underpass at the Rijksmuseum. A lot can go wrong in the process, but the projects are ultimately completed with impressive results. And they are often much more expensive than originally budgeted (as the opponents must always be won over), but that’s all part of the game in the Netherlands.

Something rather remarkable is that, when it comes to large water projects, we are very decisive and successful. Do you see that long stripe in the North down there? That is our famous Afsluitdijk, our own 32-kilometre ‘wall against the water’ with which we regulate the water in the North. And do you see the dams there in the South? Those are our Delta Works, which keep the water on the west side under control.

The Afsluitdijk runs over a length of 32 kilometres and is a fundamental part of the larger Zuiderzee Works, damming off the Zuiderzee, a salt water inlet of the North Sea, and turning it into the fresh water lake of the IJsselmeer.

The Afsluitdijk runs over a length of 32 kilometres and is a fundamental part of the larger Zuiderzee Works, damming off the Zuiderzee, a salt water inlet of the North Sea, and turning it into the fresh water lake of the IJsselmeer.© Holland boven Amsterdam

The polder model does, however, have its disadvantages. In the midst of constant consultation, there is always a chance that ultimately nothing changes, and all that remains is a vague compromise. ‘Having your cake and eating it’, ‘papering over the cracks’ and ‘wheeling and dealing’ are all typically Dutch principles.

In conflict, it is better to try to get along with your opponents, because in the end, you have to continue working together. That’s why we always disapprove of disputes in foreign parliaments. On the internet, however, there is a lot of abuse, generally from cowards looking to get attention while they sit safely behind their screens. That is what puts our solidarity under pressure the most.

Working together is necessary in our joint struggle to preserve our achievements. From a positive point of view, this is part of our ‘unity’, but the solidarity of sheep is not so credible if each is looking for their own food on higher ground. Moreover, the helpfulness that comes with solidarity may also result in too little independence. The public aspect of our polder model can be detrimental to private initiatives, too, often because a committee must first be appointed or arrangements adjusted. The need for solidarity can sometimes be as dull and grey as a drizzly day above this river delta.