Will Brussels Once Again Be European Capital of Culture?

In 2030 Brussels hopes to become the Cultural Capital of Europe once again. The city held the title in 2000 but, unfortunately, did not make an overwhelming impression on the outside world. But when we consider that Brussels is already making preparations for 2030, it seems obvious that 2000 must have something to do with it.

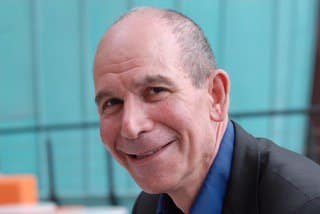

What do you still remember about Bruxelles 2000? Does the name of the Scot, Robert Palmer, ring a bell? He was brought to Brussels as a cultural commissioner in 2000, after having successfully organised a year of culture in his home city of Glasgow ten years earlier.

But in Brussels, Palmer was sailing against the wind. To begin with, Brussels was only one of nine (!) Cultural Capitals. The year 2000 was considered the millennium year so, rather than choosing just one city, nine were chosen as a nod to European contributions to global civilisation and culture: Prague, Avignon, Bologna, Krakow, Santiago de Compostela, Helsinki, Bergen (Norway) and Reykjavik were awarded the title along with Brussels. In that context, standing out from the crowd internationally was no mean feat.

When Brussels was European Capital of Culture in 2000, Robert Palmer had to manage the project.

When Brussels was European Capital of Culture in 2000, Robert Palmer had to manage the project.© www.onasis.org

The institutional complexity of Belgium did not, of course, make Palmer’s task any easier. In Brussels, the responsibility for culture rests at many levels: municipalities, communities, community commissions, the federal government… (The situation is comparable to that of Well-Being and Health. The weaknesses wrought by this division of powers were mercilessly exposed during the Corona crisis.) Since the Brussels-Capital Region itself did not yet have any cultural powers in 2000, the candidacy had to be submitted by the City of Brussels – ultimately only one of the nineteen municipalities of the region.

Palmer, therefore, had to take into account the different levels of involvement when composing his team – a team that turned out to have many different ideas about the cultural year. As a result of their differences, Hugo De Greef left the team to become the commissioner for Bruges 2002. Yes, indeed; two years after Brussels, Belgium once again had a European Capital of Culture. With a brand-new concert hall, Bruges was able to provide a lasting testimony to its cultural year. Conversely, a permanent reminder seemed to be completely missing in Brussels after its (shared) reign in 2000.

Better cooperation

People within Brussels’ cultural sector look back less negatively on 2000. The showpiece of Brussels 2000 was the Zinneke Parade, an artistic procession prepared over many months by hundreds of Brussels’ residents from all quarters of the city.

The Zinneke Parade in 2018

The Zinneke Parade in 2018© Zinneke Trompe l’œil

The parade still exists, as a biennial. The formula has evolved, but the event remains eagerly anticipated by the people of Brussels. In fact, Zinneke has become much more than just a biennial festival. In an isolated part of Noordwijk, an old printing house was recently converted into a headquarters for the event and Zinneke has taken on a pioneering role in areas such as ecology and sustainability. The organisation works diligently to recuperate all kinds of building materials and wants to open up its new infrastructure as much as possible for other users.

In addition, since 2000, the Brussels cultural sector has come to realise that it has to unite in order to achieve something. An arts consultation was established on both sides of the language divide, with both sides working very closely together. The Brussels Museum Council is the umbrella organisation for the museums. The community groups on the Flemish side and those in the Francophone communities both attend the annual New Year’s reception.

The Zinneke Parade in 2018

The Zinneke Parade in 2018© OST Collective

Unfortunately, despite this broader consultation and cooperation, the cultural sector in Brussels has experienced a number of setbacks in recent years. The attacks in Paris in November 2015 and in Brussels itself in March 2016, in which many of the perpetrators were locals, had a particularly bad effect on the image of the city. Closures due to the pandemic hit the worldwide cultural sector particularly hard due to cuts in subsidies; for instance, when the stand-alone trilingual cultural magazine Agenda was abolished by the Flemish-Brussels Media.

Anno 2022

Today, cultural responsibility and power are still spread over many different levels. Due to the sixth state reform of 2011, the Brussels-Capital Region is now in charge of so-called “bicultural matters of regional importance”. For example, the KANAL centre for modern and contemporary art in a former Citroën garage on Sainctelette Square is an initiative of the region. KANAL must eventually become the showpiece. In the meantime, it does illustrate how the region continues to find its bearings in its new cultural competences: for example, the appointment of a Brussels head of cabinet as project leader was widely criticised. Proposed collaboration with the Pompidou Centre in Paris also met with objections because even though some contemporary Brussels organizations have more of a finger on the pulse than the Centre Pompidou, they still struggle to survive.

The KANAL centre for modern and contemporary art must be the showpiece of "Brussels 2030".

The KANAL centre for modern and contemporary art must be the showpiece of "Brussels 2030".© Veerle Vercauteren

Brussels Prime Minister Rudi Vervoort drew the ire of the cultural sector when he announced that cartoonist Philippe Geluck would be opening a museum near the Centre for Fine Arts Bozar, in the cultural heart of the city. Why should an entire museum be devoted to one cartoonist with one well-known character, Le Chat, when the well-established Museum of Comics has had to lay off employees for lack of financial resources?

There is some promise in the plans to develop an arts pool in the Molenbeek canal zone, on the border with Cureghem, where a whole range of organizations already have found or will find their place. Old industrial buildings are being renovated by the Urban Development Company and re-launched as creative venues. Charleroi Dance, Recyclart, the experimental community centre and concert hall De Vaartkapoen and the Decoratelier of scenographer and artist Jozef Wouters are already temporarily housed there. Cinemaximiliaan, which takes on film projects by up-and-coming young producers, has moved into a building across the street.

Once again, the Cultural Capital of Europe ?

It was, once again, Brussels Prime Minister Vervoort who took the initiative for Brussels’ second candidacy as European Capital of Culture. In a tiered system, cities must first apply at the national level, then be assessed at the European level – unless a country decides to submit only one candidacy to the European Council. There have been some adjustments to the allocation system, too. Every year there are now two or three cultural capitals throughout Europe and a list of which countries will be next, and in which year, has been drawn up. After Mons in 2015, it will be a Belgian city again in 2030.

In 2030, Belgium will celebrate its 200th birthday, which provides a strong argument for awarding the title to the capital

Internationally, the cultural capitals resonate less in recent years than they used to. Who even knows, for example, that in 2022 Luxembourg’s Esch-sur-Alzette will be the cultural capital? The selection of Esch immediately highlights the limitations of the new system. Large countries with large cultural cities or small countries with small towns all get the same chance. In terms of content, Europe does set fairly high standards. Cities should not just make a splash for one year but, rather, provide a long-term vision regarding the development of culture.

Several Belgian cities have already indicated that they, too, aspire to the title in 2030. Two strong contenders apart from Brussels are Leuven and Ghent. Leuven, recently the European Capital of Innovation, has made great cultural strides in a short period of time, including its concrete plans for a performing arts complex. According to many in the cultural sector, Ghent should have been the cultural capital in 2002, not Bruges. Ghent is bursting with cultural initiatives, including plans for major renovation works at their Flemish Opera site and at the Design Museum.

To celebrate the 200th anniversary of Belgium, the Cinquantenaire site will be renovated.

To celebrate the 200th anniversary of Belgium, the Cinquantenaire site will be renovated.Brussels has one big advantage over Leuven and Ghent. In 2030, Belgium will celebrate its 200th birthday, which provides a strong argument for awarding the title to the capital. Especially since the federal government is planning to celebrate the 200th anniversary with a renovation of the Cinquantenaire

site, which not only houses the great Royal Museums of Art and History and the Royal Museum of the Armed Forces and Military History, but also the popular Autoworld.

The park has always attracted a significant number of visitors and still does but, like the museums, it deserves a major overhaul. Only recently, Paul Dujardin, the former director-general of Bozar, was added to the site’s Art and History team, with the task of managing the renovation of the park.

Jan Goossens and Hadja Lahbib are responsible for preparing the candidacy of "Brussels 2030".

Jan Goossens and Hadja Lahbib are responsible for preparing the candidacy of "Brussels 2030".© Saskia Vanderstichele

Moreover, Brussels has been the fastest off the starting block. Last year it appointed a duo of experienced commissioners: Jan Goossens, ex-director of the Flemish Royal Theatre in Brussels, who is also active in Marseille and Tunis; and Hadja Lahbib, culture journalist for the French-speaking public broadcaster RTBF. They are supported by an expert committee that includes some big names from the cultural sector. A first report is expected from Goossens and Lahbib in mid-2022. Brussels will submit its candidacy in 2024. The verdict will come a year later.

So, what have Lahbib and Goossens already revealed about their plans? First, they want to work from the bottom-up, with significant input from Brussels’ residents. Second, as they told the Dutch-language weekly Bruzz, they ‘want to initiate a process with artists and culture that serves as an engine for other social developments such as urban planning, sustainability, democracy, diversity and social equality.’ In a sense, their words echo the trajectory of the Zinneke Parade over the past two decades. From 2024 onwards, Lahbib and Goossens want to organize biennials under the name Summer of Brussels. And they say they want to reach out and work with the other Belgian candidate cities.

The Flemish daily newspaper De Standaard has already advised the other candidate cities to take up the challenge: ‘There is one simple tactic that has the chance of success: working to become the Flemish partner of the Brussels project’.