With the Lightness of a Bird. The Art of Johan Van Geluwe

‘We have art in order not to die of the truth.’ Friedrich Nietzsche knew that the truth could be horrifying, abhorrent. Luckily, humanity had art, which made life bearable. In 1991 Marie-Jo Lafontaine used this Nietzsche quotation in an installation at the Glyptotheek in Munich: she placed large photos of red, licking flames in the dome of the museum; in the frieze around the dome Nietzsche’s quotation appeared. The recently deceased artist Johan Van Geluwe (1929-2020) would have done the same.

But he did other things.

In 2001 he placed a placard on the right side of the bridge over the Scheldt in Oudenaarde with the text: ‘Achtung! Sie verlassen das Heilige Römische Reich Deutscher Nation’. On the left side, the text: ‘Attention. Vous quittez le Royaume de France’. (You are now leaving the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation/the Kingdom of France.) With these placards he undermined the borders of current-day Belgium by reminding us of the borders in place 1,000 years earlier, when the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire had built a fort on the right side of the river in Ename while Baldwin IV, the Count of Flanders and a vassal of the French king, responded by constructing a tower on the other side.

Borders are always contingent: they are put into place, but without any ratio for their location. Still, it’s best to accept them before you want to cross them. Constant questioning or change opens a veritable Pandora’s box. Van Geluwe celebrates the contingency of borders by sincerely pretending.

He did the same with belgitude. The term was first used in 1976 by the francophone Belgian author Pierre Mertens. If the négritude of Léopold Senghor could be used, so, too, could belgitude. The Belgian soul – we used to talk about the national character, but that’s no longer allowed. Now people talk about identity, but this is also suspicious – was primarily a hollow soul, defined by what it wasn’t. Let us say that it consisted of what was leftover after the commonalities between the Flemish and the Dutch, the francophone Belgians and French had been summarised.

Or, as Jean-Pierre Stroobants wrote in Le Monde on 2 May 2005, referring to the new Flemish-Belgian wave of podium artists who were experiencing success in France: ‘There is, beyond all the differences, a link between Flemish and French speakers in Belgium, a common sense of derision, surrealism, creative genius.’ Just so you know. Belgium has not disappeared. It exists and even if the Belgians abolish it, it will continue to exist abroad.

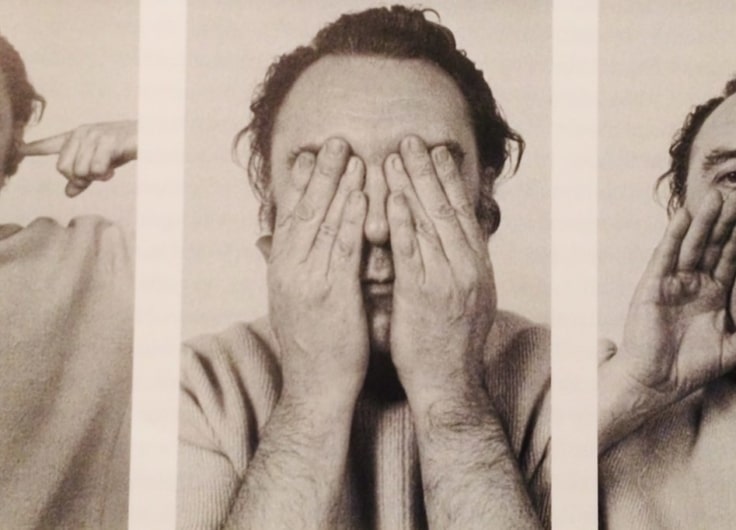

Johan Van Geluwe

Johan Van Geluwe© Stad Waregem

Even King Albert said, in his speech to government officials at the palace in Brussels, that: ‘Periodically, the outside world underlines a number of characteristics that Belgians should have in common such as our openness to other cultures, our creativity in making compromises, our pragmatism, a certain modesty and our ability to not take ourselves too seriously.’ I don’t know of any other country in the world where national identity and, thus, national pride, depend on the impossibility of feeling proud.

As of 2005, Belgium had existed for 175 years. They asked a Swiss curator to create an exhibit about the country and had their wishes fulfilled. Harald Szeemann came, saw and conquered with Belgian Visionary at the Bozar in Brussels. He had already completed Swiss Visionary and Austrian Visionary,

and claimed that he could only create these exhibitions for these types of countries; not big ones such as France or Germany. Belgium, then, was the final part of the triptych and, at the same time, his swansong, as he died just before the exhibit opened.

Szeemann changed Belgium’s old coat into a magical cloak. Perhaps it takes an outsider to do this, to approach the clichés without inhibitions. In a critique of the exhibition I discovered a pertinent question: ‘Did the exhibition, created by an outsider, capture the essential core of an unreal country or was it a superficial flirtation with the depicted surrealistic Belgian traits (…)? Is bizarreness the baseline of belgitude, if this thing called belgitude even exists?’

Luckily, there was already a Johan Van Geluwe in 2005. And Szeemann called upon him.

We know about his Sire, there are no more Flemish primitives, an ironic correction of the bitter statement of the Walloon politician Jules Destrée in his open letter to King Albert I in 1912: ‘Sire, there are Walloons and Flemings in Belgium; there are no Belgians.’

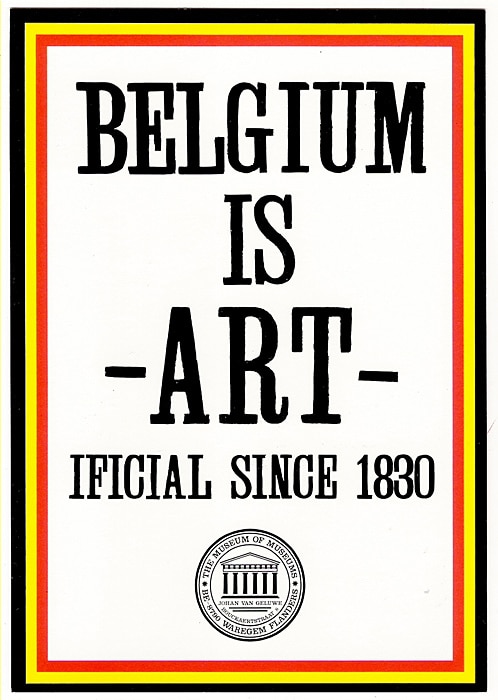

There is also his unity destroys power (eendracht breek macht/l”union case la force), the reversal of the Belgian call to arms to break power – any form of power – by forming front. But Van Geluwe’s masterpiece is his Belgium is art-ificial since 1830.

Clever in its simplicity. With ‘Belgium is Art’ he aligns himself with the post-modern glorification of identity-free and therefore human and life-affirming Kakania: a country as a work of art. But with ‘art-ificial since 1830’ he points to the artificial nature of every political construction, nation and state. It’s sufficient. With the leggerezza of Calvino; the lightness the writer asked of literature – the talent to remove the weightiness – Van Geluwe played around with belgitude and, where necessary, also with flandritude. Lightness should not be taken lightly. It is the lightness of a bird, not of a feather – in short, it’s the virtue that our society needs.