‘Yes, I Do’ and Other Words That Change the World

Linguist Marten van der Meulen had the honour to perform one of the rarest and most extraordinary speech acts: the wedding ceremony. This led him to reflect on the functions of language. ‘The language you use, shows the group you belong to.’

I was given a great honour last year. I got to be a BABS for a day, also known as an Extraordinary Civil Status Officer. For people who don’t know what this is, it probably sounds insanely boring: why would you want to be a public servant for a day?

However, a BABS is more than just a public servant. It is a position with only one purpose: you get to marry a couple on that day. So, I was a marriage officiant! In other words, I got to marry one of my friends and his beloved one (who I also happen to really like).

This in itself was already incredibly unique, lovely and amazing. Yet there was also something linguistically interesting about it. I was allowed to perform one of the rarest and most extraordinary acts of language that is known. I am of course referring to the speech act of marriage. I asked both fiancées the following question:

“Do you, First and Surnames of Fiancée 1, take First and Surnames of Fiancée 2 to be your lawfully wedded wife/husband and do you promise to faithfully fulfil all duties according to the bonds of marriage? If so, answer “I do.”

After both people said “yes”, I spoke one last sentence:

“By the power vested in me by municipality X, I now declare you husband and wife.”

© Pavel Danilyuk / Pexels

This question-answer game doesn’t seem particularly special. But it is strictly defined, and it does something that is uncommon. These words are in fact necessary

to get married. If you don’t say them, or if you don’t say “yes” (some chuckle-heads

have once jokingly said “no”), then it’s over. It means you can’t get married. You obviously also have to sign, but the words are absolutely essential. They change the state of the world.

The world-changing function makes this marriage promise a so-called performative speech act. Other examples are the christening of a ship, or the conviction of a defendant by a judge. The big difference is that in those acts the words and language are still primarily symbolic. Such words are, contrary to what is said during a wedding ceremony, not legally binding. Words during a wedding ceremony change everything, for example with respect to taxes. Not very prosaic, but it does have an effect.

he language you use shows who you are, what group you belong to, or what group you want to belong to

The name “performative utterance” was coined by American linguist J. L. Austin. He acted against a school of formal linguists who tried to capture language in schemes of “true or false.” All well and good, Austin said, but that only works if a statement describes the world, and that is not the case with wedding vows. He provided several other examples of speech acts that do not describe the world. For example, there is the promise (“I promise to do the dishes”), where you only know it’s true after the dishes are actually done.

It’s far too limited to say that language solely or even primarily seeks to describe the world. Language is largely, or maybe even primarily, intended as a social tool. In that intention language is performative, but in a manner different from the marriage ceremony. Here performative is used in the sense of acting. The language you use shows who you are, what group you belong to, or what group you want to belong to.

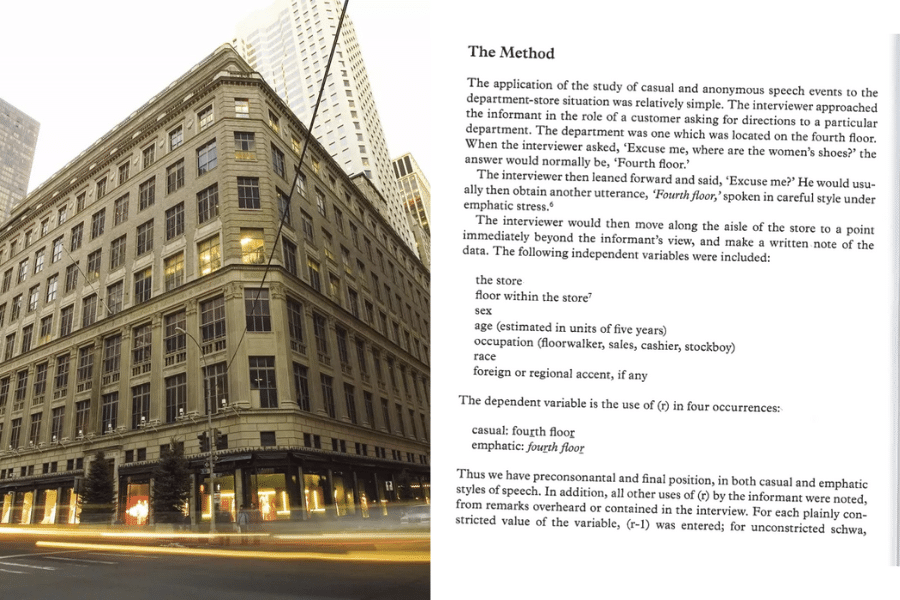

One of the most famous examples of using language to belong to something comes from the brilliant American linguist William Labov. He showed that employees of a certain department store in New York changed their pronunciation of the r sound at the end of words depending on the people of the social class they wanted to belong to. He demonstrated this with one of the most wonderful experiments in the history of linguistics.

The precise way the r sound is pronounced in English can be strongly related to social class, William Labov proved with a famous experiment in a New York department store.

The precise way the r sound is pronounced in English can be strongly related to social class, William Labov proved with a famous experiment in a New York department store.Another brilliant example also comes from Labov. He did research on the American island of Martha’s Vineyard. There, a certain vowel was pronounced slightly differently by older inhabitants than those on the mainland. What turned out: young people from the island adopted that very pronunciation, even though the linguistic change actually moved in a different direction. The youngsters wanted to show that they belonged to the island. They tried to set themselves apart from the people from the mainland. The substantive meaning of what all those people were saying didn’t change. But the social meaning was something completely different.

Labov’s research stood at the cradle of sociolinguistics, the study of the interaction between social interaction and language. Since then, there have been countless

other examples of research, all showing how language is a game of seeing and being seen. Of striking and recognizing poses. Of changing who you are in different situations. Of consciously or unconsciously using words or sounds to belong to a group, or distancing yourself from it. Of language as clothing, jewellery or accessories.

In the game of seeing and being seen, we use language as an ornament

I really enjoy language as a game, as an ornament, and as a pose. And as a linguist, I realize this when playing the language game. Last spring, I was sitting in the stands at a basketball game, of the LA Clippers, for the first time. I’ve occasionally been watching basketball games for years, so I know the rules quite well. However, I was not familiar with supporter behaviour. I got the hang of it quite fast, though. And so, in the third quarter, I also put my hand in the air, index finger and thumb pressed together and other fingers extended, when a three-pointer was made. Just like everyone else around me. I was showing that I wanted to fit in. A bit much, but also incredibly interesting.

Describing the world is actually the most boring feature of language. As magicians or gods, we also create that world, and we create ourselves in

it. Is that not far more interesting?