‘You Know Where Your Grave Is, Don’t You?’

In recent years, hundreds of thousands of people have visited the scars left by the First World War along the French-Belgian Front. More than ever before, in fact. But war tourism is not a new phenomenon. In the spring of 1919, as the first inhabitants of the devastated border area returned, tourists were already following in their wake. From the rubble a flourishing memorial sector emerged, built on cooperation and reconciliation. A century after the end of the Great War, these ideals are increasingly disappearing into the background, and war tourism has a much less critical dimension.

For a lot of the returning inhabitants, the first concern was to build a temporary home. Somewhere where they could not only live, but they could also entertain the tourists, who were a first source of income for many. On the whole, the early visitors did not stay for long. They came, by taxi or bus, to Nieuwpoort, Diksmuide or Ieper (Ypres) from the coastal town of Ostend and returned the same evening. For local residents it was a case of trying to sell them souvenirs, some food and drink, or perhaps a guided tour.

That was the situation apparently when the British travel journalist and veteran Stephen Graham visited Ieper, in August 1920.

“Ypres is terribly empty. Hundreds of thousands of eyes would look on it but there are few people who come to look at it – just ones and twos who stand diminutively in front of the great ruins and peer at them like the conventional figures in an old print. This absence of the living intensifies the strange atmosphere. It is said that the city will build itself up again, but it is possible to feel some doubt on that point. Perhaps Ypres will never be built again. At present it has some hundred and fifty places where they sell beer to two where they sell anything else. Its string of wooden hotels with cubicle bedrooms do not pay. The curious come for an hour or so from Ostende but do not spend the night. There is a sense of emptiness and tragedy which cannot be dispelled”.

Battlefield guides

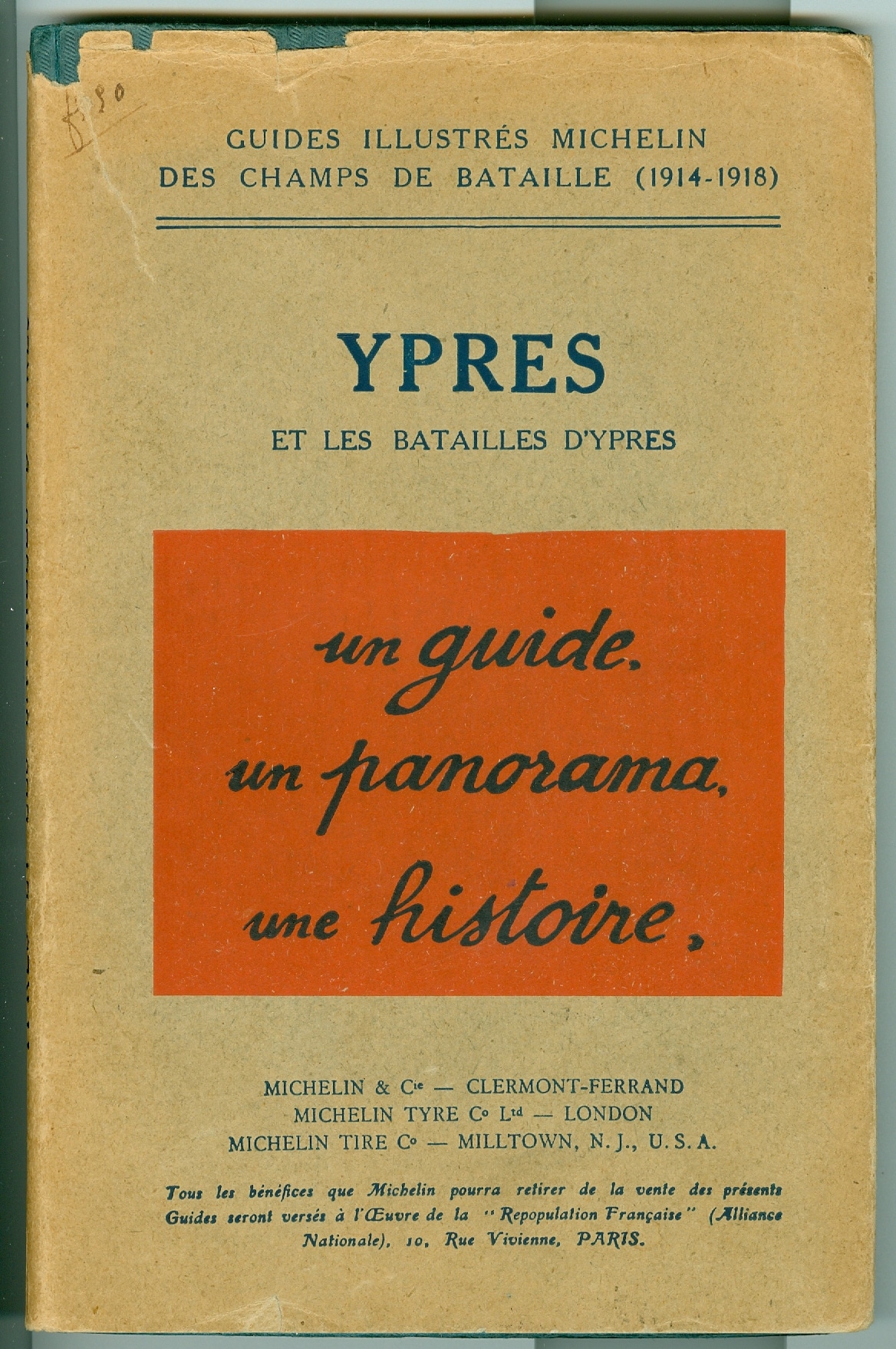

Nonetheless, war tourism was reasonably well developed by then. The French tyre manufacturer Michelin published the first guide to the First World War as early as 1917. It was a guide to the battlefields of the Marne, where fighting raged in September 1914. The guidebook was part of the series of Guides illustrés that the tyre manufacturer had started publishing in 1900, with a view to promoting car tourism and the tyres it produced. But in 1917 a special new series was started, the Illustrated Michelin Guides to the Battle-Fields (1914-1918). The war was still not over but, with the German retreat to the Siegfried Line, the front had shifted northwards and car drivers could reach the glorious battlefields at the Marne. The official French story was that that was where the fatherland was saved. Nonetheless, apart from members of the military with a few days’ leave, few visitors will have used the guides at that time. It is worth noting that the French and English versions were brought out simultaneously.

© In Flanders Fields Museum

However, Michelin & Co were clearly aiming at the period after the war. As of 1919, detailed travel guides to all the main sectors of the Western Front were published. There were already four for West Flanders and the two adjoining French departments, Nord and Pas-de-Calais: Ypres and the Battles of Ypres (1919), Lille. Before and During the War (1919), The Yser and the Belgian Coast (1920) and Arras. Lens – Douai and the Battles of Artois (1920). The English versions – for the many British tourists – were always published at the same time as the French. Later some small volumes about Antwerp and Brussels (including Leuven) were added, as were volumes on all the other significant places between the Swiss border and the North Sea.

And Michelin was not alone. Une visite à l’Yser, by A.G. De Graeve, about the Yser Front, was also published in 1919, with a great many photos taken by the cinematographic service of the Belgian army. A Dutch-language guide to the battlefields of the Yser Front, Gids van ’t IJzerslagveld, was brought out the same year. One of the most interesting guides to the Belgian Front was Ce qu’il faut voir sur les champs de bataille et dans les villes détruites de Belgique (What to see on the battlefields and in the ruined towns of Belgium). The author, Jean Massart, was a botanist and used, in his guide, the many landscape photos that he had taken long before the war as part of his study of phytogeography and nature protection in Belgium. Beside them he placed photos of the ruins of the land, villages and towns taken immediately after the war. Pictures of total devastation.

Pilgrims with a sacred mission

As reconstruction gathered pace, from 1921 onwards, the number of visitors grew. And they were by no means all tourists. A great many had good reason to come and spend a day or two in the ravaged area. Like pilgrims with an almost sacred mission, they came to look for the graves of family members or fallen comrades. The places they sought were very specific and by no means easy to find.

By 1919 the war graves services of the various armies had got to work salvaging the bodies of their armies’ dead, cataloguing the existing graves as well as they could and organising cemeteries, both old and new. It was a gigantic task. The list of those who died in Belgium, which the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ieper has been compiling continuously over the course of the last ten years, based on data from a hundred years ago, shows how impossible the task was. There were around 600,000 victims on the Belgian side of the border, roughly as many as in the former neighbouring region of Nord – Pas-de-Calais.

© In Flanders Fields Museum

The fact that many more administrative mistakes and corrections have not been noted, that more graves were not counted twice or lost through confusion (obviously that does happen) has to do with the exceptional importance that relatives and acquaintances attach to having the exact details. Everyone did the best they could to fulfil visitors’ wish to find their ‘own’ graves.

In search of a missing son

Rudyard Kipling, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, was a member of the first British war graves commission, the IWGC. In the short story The Gardener, which he wrote in 1925, he described a woman’s visit to the grave of a family member who had died in Flanders. Kipling offers a sublime insight into the world of abandoned pilgrims, tens of thousands of whom made the crossing to ‘their’ graves every year. Undoubtedly, the story is also inspired by the crossings the author and his wife made regularly as of 1919, in search of the missing body of their only son Jack, who had fallen on 25 September 1915 in Loos-en-Gohelle. Kipling has his character go to Hagenzeele, a fictitious place in Flanders that stands for all the others. Here is a passage from The Gardener.

“Then there came to her, as next of kin, an official intimation, backed by a page of a letter to her in indelible pencil, a silver identity-disc and a watch, to the effect that the body of Lieutenant Michael Turrell had been found, identified, and re-interred in Hagenzeele Third Military Cemetery – the letter of the row and the grave’s number in that row duly given.

So Helen found herself moved on to another process of the manufacture – to a world full of exultant or broken relatives, now strong in the certainty that there was an altar upon earth where they might lay their love. These soon told her, and by means of time-tables made clear, how easy it was and how little it interfered with life’s affairs to go and see one’s grave.

[…]

The agony of being waked up to some sort of second life drove Helen across the Channel, where, in a new world of abbreviated titles, she learnt that Hagenzeele Three could be comfortably reached by an afternoon train which fitted in with the morning boat, and that there was a comfortable little hotel not three kilometres from Hagenzeele itself, where one could spend quite a comfortable night and see one’s grave next morning. All this she had from a Central Authority who lived in a board and tar-paper shed on the skirts of a razed city of whirling lime-dust and blown papers.

“By the way”, said he, “you know your grave, of course?”

“Yes, thank you”, said Helen, and showed its row and number typed on Michael’s own little typewriter. The officer would have checked it, out of one of his many books; but a large Lancashire woman thrust between them and bade him tell her where she might find her son, who had been corporal in the A.S.C. His proper name, she sobbed, was Anderson, but, coming of respectable folk, he had of course enlisted under the name of Smith; and had been killed at Dickiebush, in early ‘Fifteen. She had not his number nor did she know which of his two Christian names she might have used with his alias; but her Cook’s tourist ticket expired at the end of Easter week, and if by then she could not find her child she should go mad. Whereupon she fell forward on Helen’s breast; but the officer’s wife came out quickly from a little bedroom behind the office, and the three of them lifted the woman on to the cot.

“They are often like this”, said the officer’s wife, loosening the tight bonnet-strings. “Yesterday she said he’d been killed at Hooge. Are you sure you know your grave? It makes such a difference.”

“Yes, thank you”, said Helen, and hurried out before the woman on the bed should begin to lament again.”

Kipling himself would never find his son. In 1992 a grave at the military cemetery in Haisnes was identified as his, but that has still not been fully accepted. The exceptionally large number of missing among the slain led the IWGC (renamed the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, or CWGC, in 1960) to conceive a new sort of memorial, the monument to the missing. The very first Monument to the Missing was the Menin Gate in Ieper. No other army was to copy the IWGC, and it turned Ieper into the first and most important place of pilgrimage for the people of the British Empire.

The inauguration of the Menin Gate on 24 July 1927 in Ieper

The inauguration of the Menin Gate on 24 July 1927 in Ieper© In Flanders Fields Museum

Peace and reconciliation

As of 1928, the huge veterans’ organisation the British Legion (now Royal British Legion) organised annual pilgrimages which, until the Second World War, were clearly oriented towards the idea of ‘no more war’. It was a concept comparable to that of the Flemish IJzertoren (Yser Tower) in Diksmuide, or the French Der des Ders – the war that was to make all others impossible. The British Legion acted as the organiser and tour operator. Many important literary witnesses of the first generation also expressed this strong ‘war to end all wars’ sentiment. They included, for example, Henry Williamson, R.H. Mottram and Siegfried Sassoon in Great Britain, Jean Giono and Jean Guéhenno in France, and a whole generation of authors in Germany and Austria who soon found themselves fleeing the Nazi regime, like Stefan Zweig, Joseph Roth and E.M. Remarque.

That the Menin Gate and the Royal British Legion promote almost the opposite ideology these days – which could be summarised as si vis pacem, parabellum (those who want peace must prepare for war) – is due to the Second World War, the war that the First – or Great – War was unable to prevent and which, moreover, could be labelled the good war against fascism.

In 1929, a French-Belgian monument was erected in Steenstraete as a memorial to the victims of the first major gas attack. In 1941 the Nazi occupiers had the monument dynamited.

In 1929, a French-Belgian monument was erected in Steenstraete as a memorial to the victims of the first major gas attack. In 1941 the Nazi occupiers had the monument dynamited.© In Flanders Fields Museum

The first generation of war tourists, the generation of the war itself, would to a significant extent continue to maintain this ideal of reconciliation and cooperation until the 1960s. In Ieper, the fiftieth commemoration of the war was characterised by fraternisation and newly burgeoning European cooperation. A lasting witness to this is the Cross of Reconciliation or Verzoeningskruis in Steenstraete. In 1929, a French-Belgian monument was erected there as a memorial to the victims of the first major gas attack. On it, French sculptor Maxime Real del Sarte portrayed a dramatically realistic scene of a soldier choking to death on chlorine gas. In 1941 the Nazi occupiers had the monument dynamited. Belgian, French and German veterans erected the present Cross of Reconciliation in 1961. Max Deauville, a Belgian writer and veteran of Steenstraete, interpreted their intentions like this: “Les anciens combattants belges et français ont dressé cette croix avec une volonté commune de réconciliation et de paix dans le monde”, (Belgian and French veterans erected this cross out of a shared desire for reconciliation and peace in the world.)

The fact that Deauville only mentions the Belgians and French is due to the fact that the German veterans voluntarily withdrew shortly before the ceremony. They had contributed financially to the erection of the monument but understood that their presence during the inauguration might be too sensitive for some.

In 1961 Belgian, French and German veterans erected the Cross of Reconciliation at the spot where the gas attack monument was destroyed.

In 1961 Belgian, French and German veterans erected the Cross of Reconciliation at the spot where the gas attack monument was destroyed.© In Flanders Fields Museum

Ambiguous

Fifty years later, that voice of reconciliation and peace was increasingly forgotten. A century later the official discourse is still almost exclusively nationally oriented, although the war itself was clearly transnational. It gives the war tourism dedicated to the victims of the First World War a very ambiguous dimension these days. On the one hand, there is the horror of the huge numbers of victims of the First World War, which is recognised by everyone. On the other hand, however, nostalgia for a time when national resilience and a sense of duty were central is increasingly gaining importance.

More and more, war tourism propagates an image of the world that is extremely uncritical and has not evolved, whereby the First World War was a struggle of good against evil. Commemoration of the war as a critical reflection on the greater historical significance of the First World War, or on the war as an absolute catastrophe for Europe and humanity, is slipping further and further into the background.

At a time when greater suffering is being caused by war than at any point since the end of the Second World War, the voices of the first generation of war tourists should be able to provide new inspiration.