Young, Belgian and Ambitious. Here’s the New President of Europe

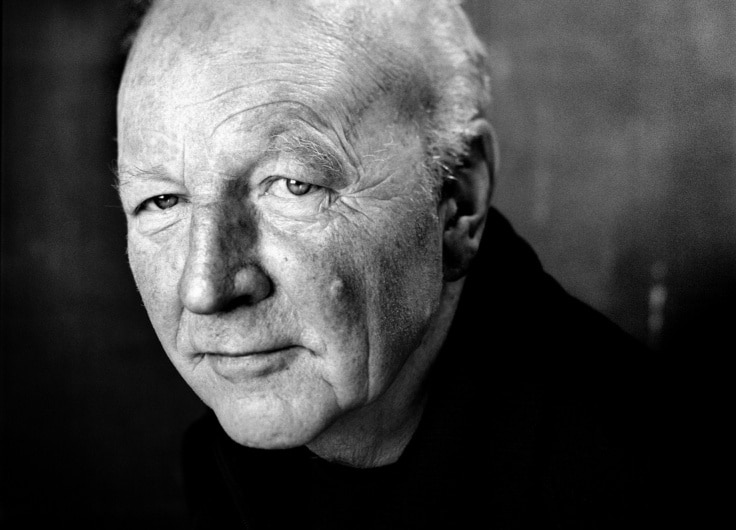

From 1 December, Charles Michel will be able to call himself the President of Europe, as the former Belgian prime minister will then chair the European Council. Michel is the second Belgian to take this top job, following Herman Van Rompuy. Portrait of a political highflyer.

Charles Michel was not yet forty when he became the Belgian prime minister in 2014, an unexpected achievement for the French-speaking liberal. His party, the Mouvement Réformateur

(MR), had advanced slightly in the elections but was certainly not the strongest contender. It had long seemed likely that the Dutch-speaking Christian Democrats would provide the prime minister, but because they held onto the post of European commissioner for Marianne Thyssen, in the end, they had to leave the prime ministerial position to another party. That’s how Michel came into view. In his twenties, he had already been a minister in the Walloon regional government and the federal government, he later became minister for development cooperation.

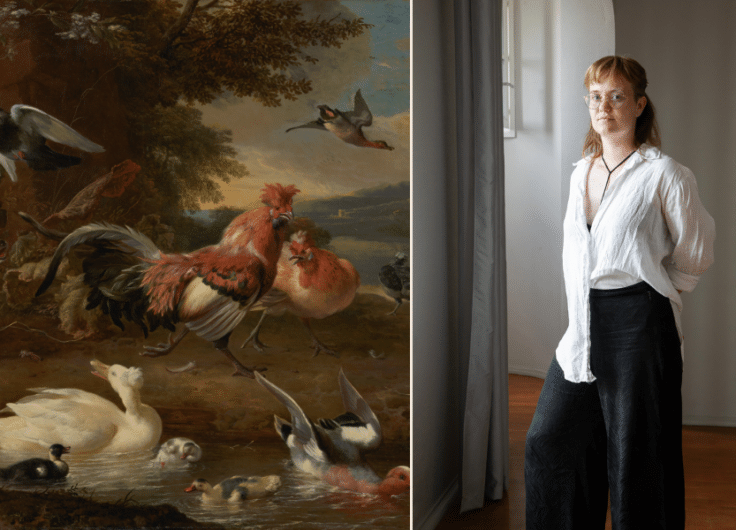

Charles Michel

Charles Michel© Belgian Federal Government

The fact that he followed such an impressive trajectory at such a young age has a great deal to do with his father, Louis Michel, former deputy prime minister, minister of Foreign Affairs, European commissioner and MEP. Nevertheless, Charles soon found his path. He is rarely portrayed as ‘just the son of’.

His term as prime minister in Belgium was difficult in many respects. In French-speaking Belgium, he came under fire because he led a government with no French-speaking parliamentary majority. The Flemish governing parties argued a great deal among themselves, earning the media nickname the ‘kibbelkabinet’ (‘the bickering cabinet’). At the start of 2019 the biggest party, the Flemish nationalist N-VA, also withdrew from the government after differences of opinion with the other parties regarding the Marrakech Migration Pact.

In the 2019 elections the MR sustained substantial losses, as did all the other parties in government. Michel’s chance of being prime minister again was slim. His party did not have enough seats to lead negotiations. There were whispers that he might be delegated to the European Commission. After two Flemish politicians (Karel De Gucht and Marianne Thyssen) it was the turn of a French speaker. That clashed with the plans of his fellow party member Didier Reynders, who has more political experience than Michel, but was passed over in the party ranking. Reynders wanted an important international position because he realised he was no longer playing first fiddle in the MR. Now Reynders had been thwarted here too. He then stood as a candidate for secretary-general of the Council of Europe, a less prominent and less weighty office. In a vote in the Council of Europe, however, he lost out.

In the end, Reynders was nevertheless nominated for European commissioner because Michel unexpectedly snagged an even higher office: in June 2019 the heads of state and government leaders of the European Union appointed him president of the European Council. Michel had never stood as a candidate, but he fitted into the puzzle that was laboriously laid out after the European elections. The liberal group was strengthened by the arrival of Emmanuel Macron and his movement. The position of chair of the Commission went to a Christian Democrat, Ursula von der Leyen. As a result, the position of chair of the European Council became available for a liberal. That position requires politicians with experience of government at the very highest level, so Michel rose to the top almost automatically. His good relationship with Macron certainly won’t have done any harm.

Charles Michel will chair the European Council

Charles Michel will chair the European CouncilThe experience of bickering Belgian governmental parties is undoubtedly handy for Michel in Europe. There are all kinds of issues on the agenda: migration, the administration of the eurozone, security policy, climate change, international political issues.

In collaboration with the European Commission, he has to convince the member states to make decisions. That’s not a simple matter, as priorities, interests and policy visions differ vastly. At the end of the day what keeps them at the negotiating table is the realisation that these issues cannot be tackled by separate countries and that they are therefore obliged to find a communal approach.

In collaboration with the European Commission, he has to convince the member states to make decisions

Michel is only the third official president of the European Council, after Herman Van Rompuy (another Belgian) and Donald Tusk. There is still some room for personal interpretation of the position. It seems that the European Commission mainly aims to play a role in the approach to internal issues, giving Michel space to take the initiative in international politics. There are a great many challenges there: the world has grown more complex recently. World leaders are less predictable and often bolder in their policy choices. The lack of stability in the Middle East, in Africa or the border region with Russia, has knock-on effects for the European Union, in part due to the migration streams that come with it.

In the past, the Union always struggled to respond in unison to these developments. It has stood by and failed to get a grip on the international scene. In the current context, Europe can hardly afford to take a diffuse approach to international politics. Creating more consensus will be a crucial task for Michel.