Young Readers Need New Heroes

The heroes of recent Dutch-language books for children and young adults act in groups, differ from the norm and are no longer all white. That’s a win, according to Professor Yra van Dijk and Lecturer Marie-José Klaver. However good the classic children’s books may be, for young readers they often connect too little with society’s current debates.

Every reader remembers them from his or her childhood: those paper heroes with whom you identified, whom you resembled – or rather hoped to resemble. Those heroes change with age: if it starts out as Otje or Pippi Longstocking, it might later turn into Lampie or Harry Potter, for example. The success of the latter is no coincidence: the young wizard is the perfect role model for teenagers. Brave and adventurous, not too macho, with a strong sense of fairness and immense autonomy. Potter also avoids being too well-behaved: he breaks more or less all the rules at his wizardry school, sometimes for a good cause but sometimes also simply out of a drive for adventure.

As Roald Dahl did in his stories, J.K. Rowling clears Harry’s parents out of the way before the story begins, so that he is alone in the world. But is he really alone? He is surrounded by father substitutes. And with his two best friends (male and female) he forms a team: they have a strong emotional relationship characteristic of today’s children’s books. Together they can take on the world. Vlo and Stiekel, by Gouden Griffel winner Pieter Koolwijk also form a cast-iron team. The tiny girl with spiky hair and the power to do magic effortlessly defeats the bullies bothering her classmate Floris. The individual as a role model has made way for a small group of heroes, or for a team of one person with an animal. Role models in children’s literature thus follow broader cultural developments. In millennial literature, too, relationships are at the centre, as demonstrated by Hans Demeyer and Sven Vitse in Affectieve crisis, literair herstel

(‘Affective crisis, literary recovery’, 2020), their study focusing on recent Dutch novels. It is in the latest children’s literature that affective relationships have come into being, according to Dutch-language expert and teacher Nienke Draaisma in an exploratory investigation into effective teaching methodology within literature education.

Besides these ‘relational’ heroes, we also see the ‘misfit’ heroes. The wonderful IJzerkop

(Ironhead, 2019) by Jean-Claude van Rijckeghem, for example, is about a girl who dreams of fighting as a soldier in Napoleon’s army. Dressed as a boy, she is drafted in place of the baker’s son, who has no wish to join the army. So in today’s children’s literature, it is no longer taken for granted that only boys can develop while girls in fact ‘shrink’ in the course of a story, as often happens in the archetypal stories. (Pratt 1981, 30).

A third trend is diversity: no longer are all heroes in Dutch literature white. And exciting stories also take place in Suriname (Het werkstuk, The essay, by Simon van der Geest, 2019) or Curaçao (De duik, The dive, by Sjoerd Kuyper, 2015). How do these new role models work? Are they like Harry Potter, or do they become top-heavy with an emancipatory or cultural message? Role models risk rapidly becoming boring if they represent a predictable moral. How do the ‘exemplary’ characters succeed in remaining children of flesh and blood?

In the three developments we sketch, there is one constant. The most important difference between an everyday character and a ‘hero’ is that the latter has autonomy: she or he has to be able to act without parental input. That fact is of course as old as Snow White. But the ending is different: it is not a prince, a wedding or adapting to the norms that save the hero or heroine, but inventiveness, self-exploration, friendship and surrogate parents.

‘Relational’ heroes

From Enid Blyton’s Famous Five (1942-1963) to Erich Kästner’s Emil and the Detectives (1931) or Hotze de Roos’s Klinkhamer twins in the Kameleon books (1949-1991), children’s literature has always had groups of main characters who together acted as ‘heroes’. So what is new about the current generation of heroic teams? The new heroes have more equal relationships than for instance the Famous Five, where the girls always drew the short straw. There are also more differences to be seen between the characters, so the reader is confronted with different perspectives.

In stories such as Els Beerten’s brilliant young adult novel Allemaal willen we de hemel (We All Want Heaven, 2008) and Alaska (2016) by Anna Woltz, there are multiple viewpoints for the reader to identify with. The young main characters together form a community, with the parents kept at a distance by the fact that they are too preoccupied with themselves, or ill or traumatised. We see many children who take on the roles of adults because their parents or teachers neglect their responsibilities.

In Alaska, a novel for and about twelve-year-olds making the transition to secondary school, Parker and Sven form an alliance, along with the dog Alaska, who rescues them physically and emotionally. The girl is traumatised by a robbery, the boy suffers from epilepsy and fears being stigmatised. Nevertheless, together they go after the robbers and succeed in finding them. As in many recent children’s and young adult books, being a child is not particularly idealised here. Being young does not automatically mean being happy. On the contrary: it is an unequal battle between institutions, dysfunctional parents and injustice in general. In this tense story, Parker conveniently helps Sven by deploying Alaska and convincing the entire community of their class to take up Sven’s vulnerable position. When he is ridiculed in a shared video clip, everyone starts sharing such clips of themselves. The ethical message that your enemies can also become allies goes down very well in early secondary school.

Other heroes

Youth literature has always been tasked with adding to the reader’s self-knowledge – young readers for instance become more aware of their own norms and values when confronted with a different world. This is primarily achieved through identification with the character from whose perspective the story is told. Focalisation (whose eyes do we see through?) is therefore a powerful tool for influencing the sympathy and moral judgement of readers.

Others point out the danger of too close an identification. Youth literature expert Maria Nikolajeva, for instance, rightly argues for some distance between the young reader and the main character: it is also important to be curious about a character who is unpleasant or ill, for example. Maintaining distance from the narrator and the narrative while still having empathy is a literary competence that the young reader needs to develop, Nikolajeva believes.

Youth literature has always been tasked with adding to the reader’s self-knowledge

Historical youth literature lends itself perfectly to this, as the characters are different anyway: they live in a different time and experience things that cannot happen in the reader’s real life. Older historical novels sometimes concealed that ‘otherness’ and presented so-called universal heroes promoting a ‘naturalised’ ideology. This makes issues such as differences between men and women from the past seem justified. ‘The protagonist eventually internalises existing, established values,’ write the Flemish children’s book experts Vanessa Joosen and Katrien Vloeberghs, and the non-critical reader takes over that attitude.

In popular older youth novels such as Hasse Simonsdochter (1983) by Thea Beckman, sexual threat and violence against a female main character are presented as almost inevitable. But in the recent IJzerkop, Jean-Claude van Rijckeghem makes it clear that forced sex is not normal: the protagonist Stans is independent, free-thinking, questions the existing gender and sexual norms and succeeds in breaking out of the heteronormative straitjacket. Increasing numbers of authors of historical novels for young readers understand the art of not completely reproducing historical inequalities, leading to surprising life courses and plot twists which are also interesting to the adult reader.

We have singled out IJzerkop to show how perspective and autonomy can be used in a historical story which appeals to today’s young readers accustomed to equality between men and women and to gender fluidity. Jean-Claude van Ryckeghem narrates his stylistically very strong novel from the alternating perspectives of the eighteen-year-old Stans and her younger brother Pier. Pier and his father’s traditional views about women are contradicted in Stans’ chapters. Since the reader often has advanced information from Stans’ chapters, the male family members sometimes come across as rather silly. Dramatic irony is far more convincing than moralism or indignation.

A main character from Napoleonic times can function as a credible role model for twenty-first-century readers

The writer also bestows upon Stans’ unprecedented freedom to do as she pleases: put on men’s clothes, fight, kiss girls, go travelling and take revenge upon the man to whom she was married off to pay her father’s debts. And it works: Pier learns to accept his sister as she is, her army comrades grow fond of her because she is brave and sensitive and the marriage contract between her father and her husband goes up in smoke. Only the parents continue to denounce Stans, but at the end of the novel she can expect no further trouble from them, as she travels to Vienna on the roof of a mail coach, heading for freedom and love. So a main character from Napoleonic times can function as a credible role model for twenty-first-century readers.

The twenty LGBTQ+ kids aged sixteen to twenty-three who were interviewed by Edward van de Vendel for the non-fiction book Gloei (Glow, 2020) are also role models: they speak open-heartedly about their search for their sexual orientation and gender identity. It is remarkable how often they have to deal with rejection by their parents, classmates and teachers in complete loneliness ‒ it is not only in fiction that parents abandon their children.

Diverse heroes

Youth novels with non-white heroes can also be problematic when they take place in the past, for instance during slavery. How does the author reconcile the historical situation with contemporary views on equality and justice with which the young reader will have grown up, without becoming bogged down in anachronism? Who are the heroes in such a story?

Dolf Verroen has dealt with this problem skilfully from a literary perspective in the controversial novel Hoe mooi wit ik ben (‘How beautifully white I am’), published in 2016 (and ten years earlier with the equally provocative title Slaaf kindje slaaf, ‘Slave child slave’), in which, without criticism or context, a white girl from a rich background is given a black girl ‘as a gift’ for her birthday. Since the enslaved girl has no rights, in this children’s book it is ‘normal’ for the white main character to order the girl around and repeatedly emphasise her white superiority. Although Verroen had no racist intentions, the book caused a commotion in 2020. This was sparked off by a reaction from a young reader who was indignant that her nine-year-old half-Antillean little sister was given the book to read without supervision or explanation in school. ‘The book caused her a lot of pain,’ the older sister wrote on Facebook. Bol.com placed a trigger warning on it and the publisher Leopold hastened to publish a lesson plan in which the historical context of slavery was explained, alongside questions for the class to discuss.

Similarly, Volle Maen (‘Full moon’, 2018) by Luc Hanegreefs, a children’s novel about the slave trade, can easily lead to misunderstandings because both the white characters and the narrator express racist opinions, without distancing themselves from the cruel fate of the enslaved people on the ship and on the plantations. The white main characters are not role models because they do not defend the enslaved people and the black main characters are barely given the chance to be heroic.

In De reis van Syntax Bosselman (‘The journey of Syntax Bosselman’, 2018), Arend van Dam succeeds very creditably in making a role model of a formerly enslaved Surinamese man. He does so on the one hand by allowing the reader to watch along with his main character Syntax Bosselman, a contemplative and fatherly man of sixty, and on the other hand by representing historical reality in a documentary manner, so that the character’s historical context becomes clear. Syntax is de facto a free Surinamese citizen when in 1883 he travels from Paramaribo to Amsterdam to participate in the world exposition. But in reality, he is not really free because the colonial thinking continues and he is put on a show in Amsterdam as a ‘native’. Van Dam reveals how intertwined colonialism, racism and suppression are in the chapters about his archive research for the book.

Recent titles are not only about slavery but also about an exploration of the relationship between the Netherlands and the former colonies

Recent titles are not only about slavery but also about an exploration of the relationship between the Netherlands and the former colonies. ‘Straightforwardly’ non-white heroes are thin on the ground in Dutch children’s literature: colour always has to be the theme, and generally, then it’s about mixed-race issues. A classic heroine is Eva from Simon van der Geest’s Het werkstuk, who goes on a ‘father quest’ all on her own into Suriname’s interior to search for the father who fled from the Netherlands, where he could not put down roots. Her school friend Luuk supports her through thick and thin.

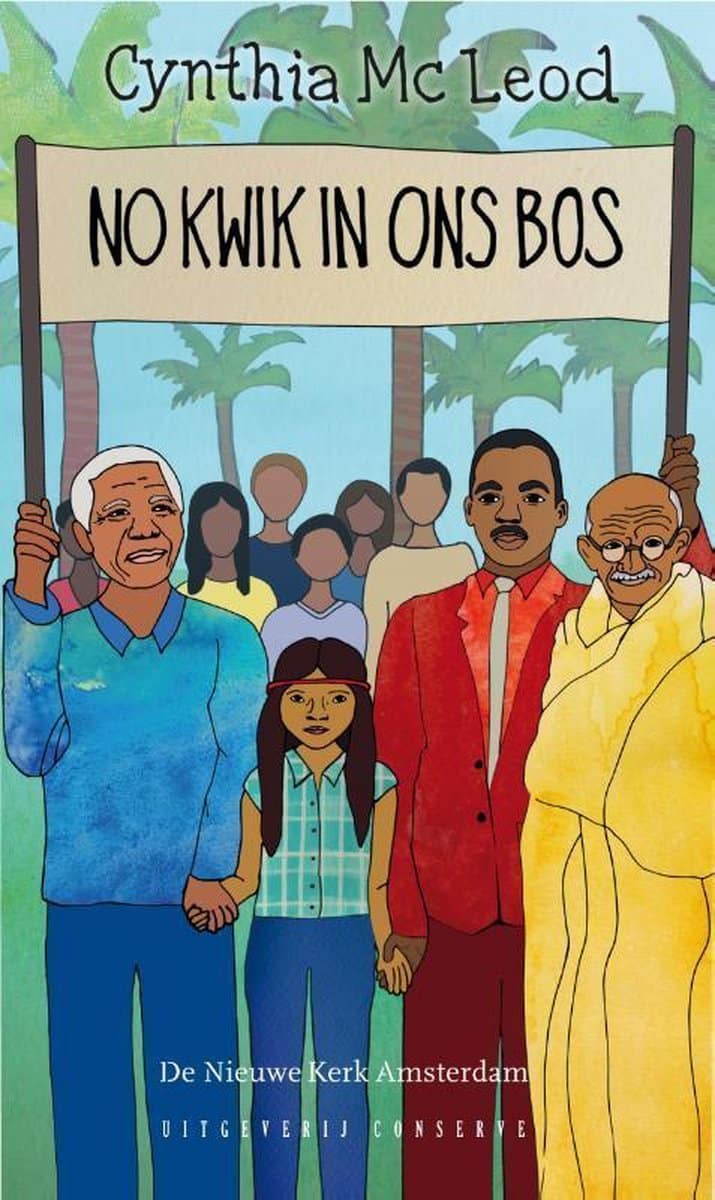

This mixed background is also a theme in the autofictional novels for young adults by Simone Atangana Bekono, Johan Fretz, Raoul de Jong and Etchica Voorn as well as in children’s literature ‒ besides Het werkstuk, see also Otis (2017) by Martijn Niemeijer. Children’s literature in the Dutch-language region is in fact still primarily written by white children’s authors. An exception is No kwik in ons bos (‘No mercury in our forest’, 2017) by Cynthia McLeod, although there the heroine is emphatically in service to the thematic and cultural message: how do native Surinamese people live?

Young readers wishing to read about role models of colour shaped by authors of colour now often turn to American and British young adult literature. The Hate U Give (2017) by Angie Thomas, Felix Ever After (2020) by Kacen Callender and Aces of Spades (2021) by Faridah Àbíké-Íyímídé are popular English-language young adult novels which are also devoured by young Dutch readers. The heroes are not only non-white but also for instance homosexual or transgender and champion athletes. On TikTok enthusiastic readers record review videos under the hashtag #boektok and exchange tips about their favourite books.

Today’s heroes

These hyper-topical books which engage with current debates in society do not automatically appear on the radar of adult readers who are not on TikTok because they are not discussed in the newspaper literary supplements. Nevertheless, it is of great importance to keep up with what good writing is being produced. Not that there is anything wrong with Otje, but, as writer Bibi Dumon Tak convincingly argued in her Verwey lecture (2021): both teachers and parents are rather too keen to recommend titles from their own childhood, as well as to read them to children. Carers and teachers must take responsibility when it comes to diversity and topicality in the choice of books.

Young readers wishing to read about role models of colour shaped by authors of colour now often turn to American and British young adult literature

Recently a parent on Facebook asked which books were suitable for her nine-year-old son, and in the responses there followed forty-eight titles of which five had girls as main characters. Only one of the recommended books had a non-Western main character.

If we really want to encourage pleasure in reading as a source of literacy, then writers, parents, teachers and librarians must get down to work: create, search for and promote Today’s Heroes.