On a visit to the Flemish city of Ypres, Derek Blyth discovers a museum dedicated to the horror of war, a beer brewed in an underground fortification and a nightly ceremony that might go on for ever.

‘Two portions of chips and two beers, mate,’ the man said. The owner nodded. He tossed the chipped potatoes in the bubbling fat and pulled two cans of beer out of the fridge. ‘Here you go,’ he said.

I might have been in a small town in England. But Frituur De Leet is in the ancient Belgian town of Ypres. The houses all around the square are neat Flemish brick buildings. The traffic signs are in Dutch. But Ypres, (or Ieper, in Dutch) feels very British.

Everywhere you look, there are signs in English, cars with UK number plates, tour buses run by British companies. They have all come for one reason.

Great Market Square of Ypres

Great Market Square of Ypres© Reisroutes

The First World War may have ended over a century ago, but it is still part of everyday life in Ypres. No matter where you look, there are photographs, memorials, cemeteries, and souvenirs. The streets are crowded with war tourists who come from all over the world, but mostly from the United Kingdom.

Something like 70 percent of visitors to Ypres are war tourists and many hotel rooms are booked by the British. They can spend the night at the Albion Hotel, shop for tobacco at Tommy’s Souvenir Shop, and book a battlefield tour at The British Grenadier Bookshop.

The St George's Memorial Church is modelled on a traditional English parish church.

The St George's Memorial Church is modelled on a traditional English parish church.© Visit Ieper

When you step inside the St George’s Memorial Church, you could almost be in England. The church in the heart of Ypres was built in 1928 for the thousands of war pilgrims visiting Ypres. Designed by Reginald Blomfield, it is modelled on a traditional English parish church. The interior is crammed with brass memorials with names of schools, regiments or individual soldiers.

A narrow path next to the church leads to a hidden garden with a few wooden benches. This was once the schoolyard of the tiny Eton Memorial School. It was founded by the elite British school in 1929 in memory of 342 former students who died during the war.

The school served the small British community that had settled in Ypres after the war, including the children of the many gardeners who looked after the war cemeteries. But it was evacuated in 1940, just before the German army arrived for the second time in Ypres.

The school never reopened. The former playground is now a silent and deserted spot in the heart of Ypres. I sat on a wooden bench trying to understand the meaning of this ancient city.

The St George's Memorial Church was built for the thousands of British war pilgrims visiting Ypres.

The St George's Memorial Church was built for the thousands of British war pilgrims visiting Ypres.© St George's Memorial Church

*

‘No tooting between here and Ypres,’ Edith Wharton was told as she drove towards the Flemish city in 1915. The American writer had set off from Paris by car with a free pass to tour the war zone and write about what she saw. She arrived to find the ancient cloth town in ruins. ‘Not a human being was in the streets,’ she wrote. ‘We had seen other ruined towns, but none like this.’ As she approached the ruined Cathedral, the German guns began shelling the city, and she quickly drove off to the relative safety of Poperinge.

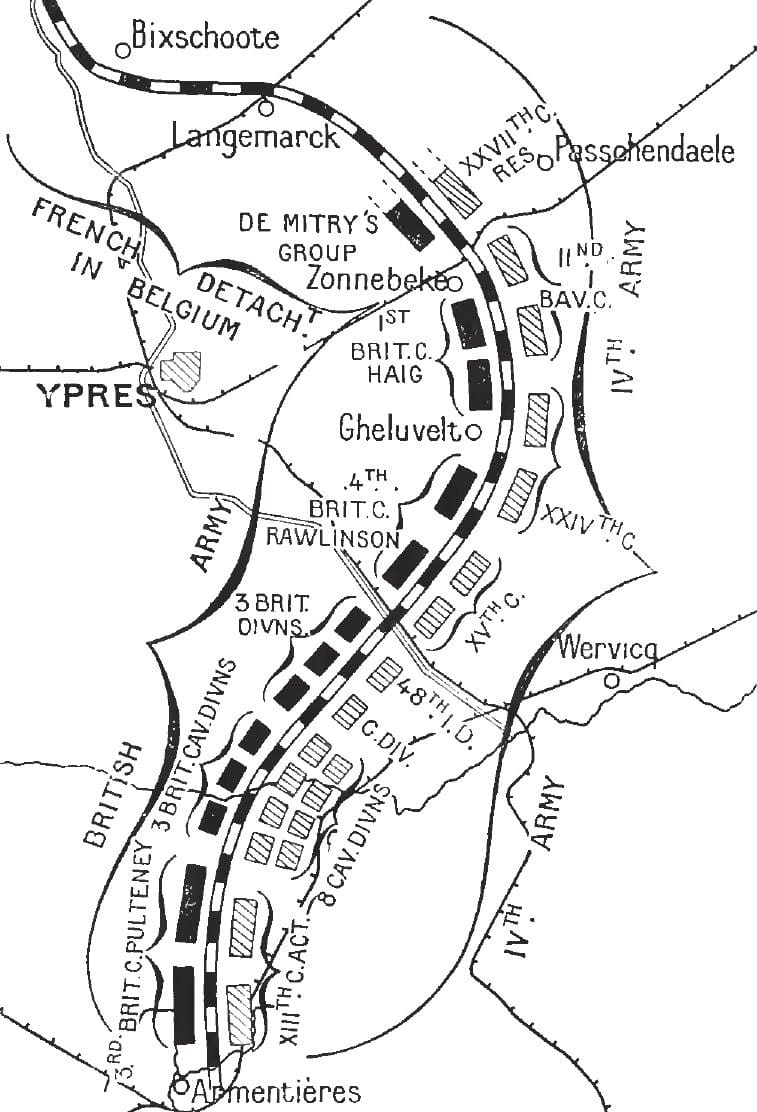

The German cavalry had entered Ypres in the early months of the war, on 7 October 1914, but they left within a few hours carrying off 8,000 loaves of stolen bread. For the next four years, they tried desperately to capture the town. But they faced fierce resistance from the British army, which had dug a protective line of trenches that became known as the Ypres Salient.

Diagram of French and British forces (left) and German forces (right) near Ypres, October 1914

Diagram of French and British forces (left) and German forces (right) near Ypres, October 1914© Wikimedia Commons

Located on the high ground around Ypres, the German guns bombarded the city incessantly, with an estimated 20 shells exploding every minute. The slow destruction of Ypres set a precedent that would be repeated later in Rotterdam, Dresden, Tokyo and, most recently, the cities of Ukraine.

The destruction of Ypres was captured on camera by two local photographers, Maurice and Robert Anthony. They began their careers in the early 20th century taking photographs of Ypres and its well-off citizens. Then war came. The brothers stayed on for a few months. Robert photographed the cloth hall in flames. His dramatic shots were reproduced in newspapers across the world, strengthening the case for war in Britain and America.

Soldiers on their way past the remains of the Cloth Hall in the destroyed centre of Ypres.

Soldiers on their way past the remains of the Cloth Hall in the destroyed centre of Ypres.© Australian War Memorial

I met Anthony’s three daughters once at an exhibition in Ostend. They explained how their father kept a unique record of each photograph, marking it in white ink ‘Photo Anthony d’Ypres’ followed by a seven-digit number.

Australian soldiers on a duckboard track passing through Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres salient, 29 October 1917.

Australian soldiers on a duckboard track passing through Chateau Wood, near Hooge in the Ypres salient, 29 October 1917.© James Francis Hurley / State Library of New South Wales

Maurice Anthony returned after the war was over to photograph the destroyed city as it slowly returned to life. One of his photographs shows a tourist bus parked in front of the ruined cloth hall with a sign announcing ‘Excursions to the Battlefields.’

By the end of the war, the city lovingly photographed by the Anthony brothers was almost totally destroyed. Winston Churchill, who was the British Secretary of State for War, wanted it permanently left in ruins as a memorial. ‘I should like to acquire the whole of the ruins of Ypres,’ Churchill declared in 1919. ‘A more sacred place for the British race does not exist in the world.’ But local residents had other ideas. They were reconstructing their city even as Churchill spoke.

This photograph depicts the devastation of Ypres during the first years of the First World War. The fortifications can be observed very well. In the middle of the doomed city, the Hall Tower still stands out. German shelling would later bring everything down.

This photograph depicts the devastation of Ypres during the first years of the First World War. The fortifications can be observed very well. In the middle of the doomed city, the Hall Tower still stands out. German shelling would later bring everything down.© Westhoek Verbeeldt

Ruins of Ypres in 1919

Ruins of Ypres in 1919© Wikiwand

Several local figures shaped the future identity of Ypres. One of them, René Colaert, served as burgomaster of Ypres from 1900 to 1921. While Churchill urged him to leave his city in ruins, like Pompeii, Colaert took the side of local citizens who wanted to rebuild their homes as quickly as possible.

The city architect Jules Coomans had worked on the restoration of several historic buildings before the outbreak of war, including the cloth hall and belfry. He returned to Ypres once peace had been restored to work on the reconstruction. He used old plans and photographs to get every detail right. The houses were carefully rebuilt in their original style, as if the war never happened. But if you look closely, you can sometimes spot shell holes in the old stone foundations.

The only place where there is any evidence of the destruction is in the ruined cloister behind St Martin’s Cathedral. The abandoned garden is strewn with fragments of architecture and sculpture from buildings destroyed in the war. Nothing is labelled. This collection of unidentified rubble is all that is left of a lost city.

Just after World War I, emergency housing was built on the Minneplein. It served as the temporary centre of the city.

Just after World War I, emergency housing was built on the Minneplein. It served as the temporary centre of the city.© Westhoek Verbeeldt

The reconstruction took many decades to complete. Meanwhile, the local population had to live in temporary houses built on a field called the Minneplein (Love’s Place) outside the city walls. This gradually evolved into a small town, with its own town hall, church and schools.

I had read about one surviving temporary house from 1919. It was down one of the town’s many narrow brick-paved lanes, next to Slachthuisstraat 20. The modest wooden house constructed in 1919 is still standing as a reminder of the difficult years after the war ended, although it looks as if it might collapse one day soon.

The only surviving temporary house from 1919

The only surviving temporary house from 1919© Discovering Belgium

Within a decade, most of the brick houses had been rebuilt. But the work wasn’t done. The Gothic Cloth Hall was a much longer project. Built in the 13th century, it was the largest secular Gothic building in the world. The reconstruction called for skilled craftsmen who could replicate the delicate stonework carved by mediaeval masons.

The workmen were still toiling away on the project in the 1950s and 1960s. The last of the scaffolding was finally removed in 1967. The building exact in every detail, apart from the modern figures of King Albert and Queen Elisabeth placed in a niche at the foot of the belfry, next to the mediaeval figures of Boudewijn IX and Margaret of Champagne.

The Cloth Hall was the largest secular Gothic building in the world.

The Cloth Hall was the largest secular Gothic building in the world.© Flanders Fields

Once it was restored, the Cloth Hall had to be given a purpose. A war museum was the obvious answer. It was originally called the Ypres Salient Memorial Museum. A traditional war museum, filled with weapons, equipment and military maps. But then it changed. In 1998, it was renamed In Flanders Fields Museum, after the famous poem by the Canadian doctor John McCrae. The weapons were mostly cleared out. The museum adopted a more critical approach that focused on the literature, poetry and music that had come out of the war.

The new museum was largely shaped by the coordinator Piet Chielens. He grew up in the West Flanders village of Reningelst surrounded by war cemeteries and shell craters. An expert on the history and poetry of the Ypres Salient, he gave the new museum its unique identity. Not so much a military museum, more a peace museum.

The museum changed again in 2012 as plans were being laid to mark the 100th anniversary of the war. The music and poetry were given a smaller part in the story, as the focus shifted to the gentle hilly landscape around Ypres where the trenches were dug and the battles fought.

The British indie band Tindersticks was commissioned to compose a soundscape to accompany visitors as they moved through the museum. After a visit to Vladslo German Cemetery, the band produced a haunting, sombre soundtrack. It is no longer played due to negative reviews, a museum employee told me.

In Flanders Fields Museum is a peace museum rather than a war museum.

In Flanders Fields Museum is a peace museum rather than a war museum.© Visit Ieper

The museum’s changing focus reflects a change of mood. It was originally about weapons, and ways of killing. Then it got into literature and music. Now it is about the lives that were destroyed by the weapons. There is more information about Belgians caught up in the war. Less about the battles. And, if you want to hear the Tindersticks soundscape, you can always buy the CD in the shop.

When you enter the museum, you are given an electronic bracelet that lets you follow the stories of two of the many millions whose lives were destroyed by the war. It might be a soldier from Australia, or a nurse from Ireland, or a Belgian mother forced to flee her home.

In Flanders Fields Museum tells the story of the lives that were destroyed by the weapons.

In Flanders Fields Museum tells the story of the lives that were destroyed by the weapons.© In Flanders Fields Museum

As you walk around, you are confronted with screens that tell the stories of your random victims. Other screens show actors who play the part of soldiers, nurses or refugees. On one, actors recreate the Christmas truce of 1914 when soldiers from the two sides briefly laid down their weapons to sing songs. On another screen, doctors and nurses speak of the horrors they experienced.

It is now possible to climb the steps of the belfry

for the first time. The winding steps take you up to a narrow platform where you can look out on the hills and woods where the fighting happened. It reminds you that there is a lot to discover beyond the city walls.

The story doesn’t end in 1918. The final exhibit features two old wooden chairs. Each one has a label attached. Ukraine, it says on one. Russia, on the other. They come from a collection of 120 ‘memorial chairs’

assembled by the artist Val Carman. Sent from all over the world, the chairs were displayed in the museum during the ceremonies to mark the 100th anniversary of the end of the war. The message is obvious. Come on, sit down and talk.

*

St Martin's Cathedral

St Martin's Cathedral© Visit Ieper

I was beginning to understand the history of Ypres. It is a city that had been attacked many times in the past, long before the Germans arrived in 1914. A huge painting in St Martin’s Cathedral

illustrates the Siege of Ypres back in 1383. Painted in 1667 by Joris Liebaert, it shows the city under attack from an army composed of troops from England and Ghent. The siege failed after local people prayed for help from the Madonna of Thuyne, but it ruined the town.

The city ramparts

The city ramparts© Visit Ieper

A walk around the city ramparts is a good way to understand the many layers of history. These massive brick walls have been attacked, destroyed and rebuilt many times, leaving behind traces from every period. The massive stone Poedertoren near the railway station was once used to store gunpowder. The Predikherentoren further around the walls is all that survives of a massive round tower built in the 14th century during the Burgundian period. And the hidden Poterne Staircase runs down from the ramparts to the city moat. Built in the 17th century, it formed part of a secret network of tunnels and stairs used to defend the city.

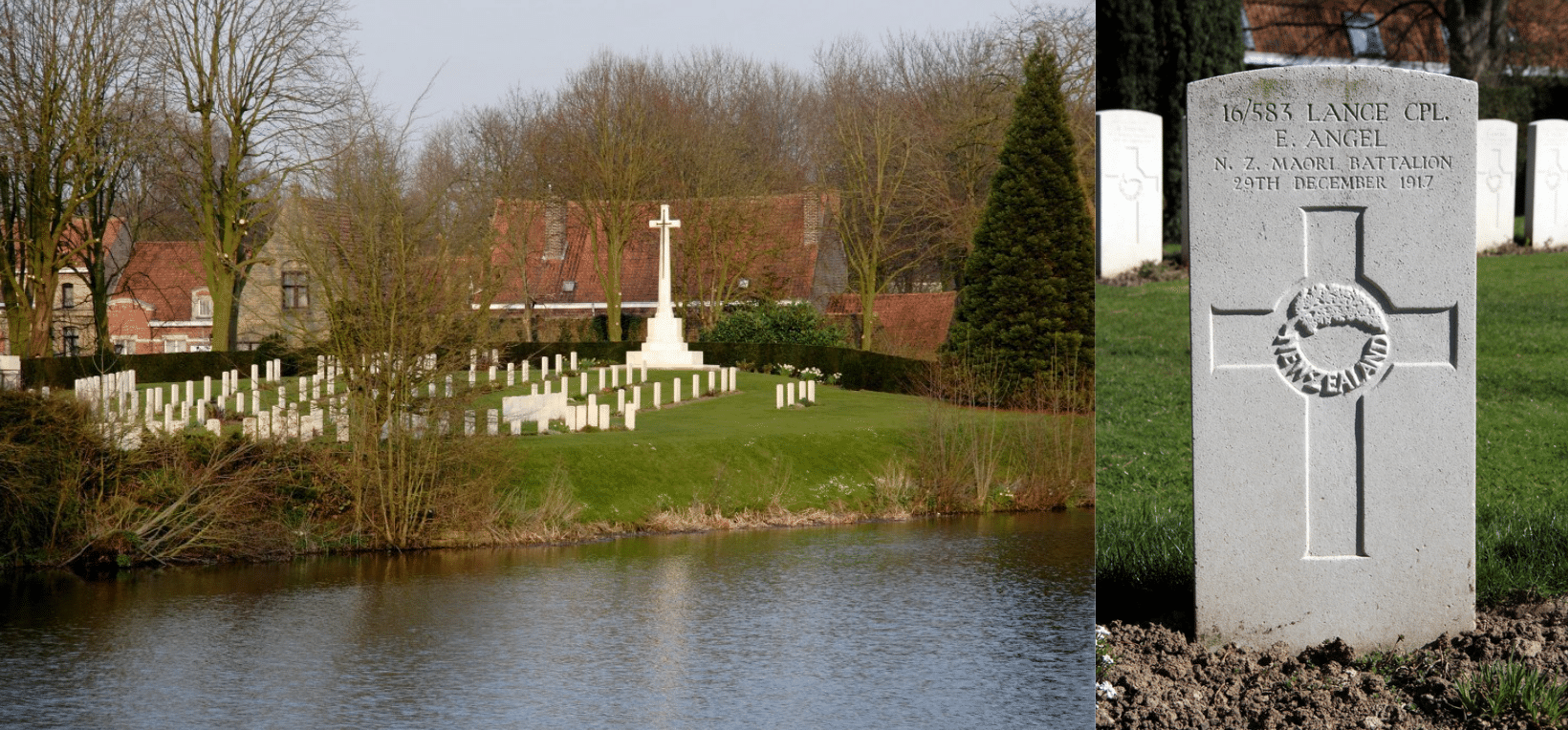

The Ramparts Cemetery is the most haunting spot. Built on sloping land on the edge of the moat, this hidden cemetery has just 193 graves, including six from the New Zealand Maori Battalion and six Australian soldiers killed by a single shell. The writer Rose Coombs, who wrote a guide to the Ypres battlefields in 1976, was particularly fond of this cemetery. Her ashes were scattered here after she died in 1991.

The Ramparts Cemetery is the final resting place of 193 killed soldiers.

The Ramparts Cemetery is the final resting place of 193 killed soldiers.© Commonwealth War Graves Commission

There are other hidden places that lie buried deep below ground. The Kazematten brewery occupies ancient 17th-century casemates below the city walls where British troops printed a humorous trench newspaper called The Wipers Times. The brewhouse was launched here in 2014 by the famous Sint-Bernardus brewery in Watou. It produces a golden ale called Grotten Santé and a light beer called Wipers Times.

The Kazematten brewery occupies ancient 17th-century casemates below the city walls.

The Kazematten brewery occupies ancient 17th-century casemates below the city walls.© Visit Ieper

It sometimes seems as if Ypres has no history apart from the war. Yet this was one of the great cloth-producing towns of the Middle Ages. ‘It was an economic powerhouse in the 12th and 13th centuries,’ argues Bart Lambert, an expert in mediaeval history. Its cloth was sold in England, Italy and even Russia. The skill of its cloth makers was praised in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

The city finally got its own museum in 2018 when the Yper Museum

opened in a wing of the cloth hall. It sets out to tell eleven centuries of history from the small collection of fragments salvaged from the ruins. Some of the exhibits were moved here from a School Museum when it closed down. Others were saved from a folklore collection.

The Yper Museum tells eleven centuries of city history.

The Yper Museum tells eleven centuries of city history.© Visit Ieper

The new museum doesn’t get many visitors compared to In Flanders Fields. Yet it is an interesting place to spend an hour with information panels in four languages. It is good on the violent history of Ypres which began with a Viking invasion in 800. You discover that the city had reached its peak as long ago as 1385. And you learn about a weird local festival that involves throwing cats from the top of the Belfy. Live cats, in the Middle Ages. Stuffed toys now, I should add.

The museum has filled an entire room with its collection of mediaeval badges. No one knows exactly the significance of these tiny metal tokens, which are decorated with saints, professional tools, or sometimes erotic symbols. But that just makes them all the more intriguing.

The museum’s main attraction is a film room where they screen a dramatic history of Ypres. This will be interesting, I thought. But it was rather strange, more like a Monty Python sketch. A giant human foot stamping on Napoleon’s head, that sort of thing.

The silly film soundtrack spills over into rooms dedicated to the golden years just before the war. Some quiet piano music might better fit the collection of period photographs by Maurice and Robert Anthony. They capture the gentle, contented mood in Ypres, with families strolling in the meadows outside the city walls, and farmers selling their vegetables outside the cloth hall.

Self portrait of Ypres artist Louise De Hem (1866-1922)

Self portrait of Ypres artist Louise De Hem (1866-1922)© Ypres Museum

The museum also displays paintings by the Ypres artist Louise De Hem. She became a successful artist at a time when Belgian women were banned from art school. Her gentle pre-war portraits capture a lost world of bourgeois wives and rural girls.

While most of the city was destroyed above ground, there are layers below the foundations that survived the shelling. During building work next to the St Nicholas’ Church, researchers uncovered a huge mediaeval cemetery containing at least 1,200 skeletons. The remains are now being examined by a team that plans to release its findings in 2024.

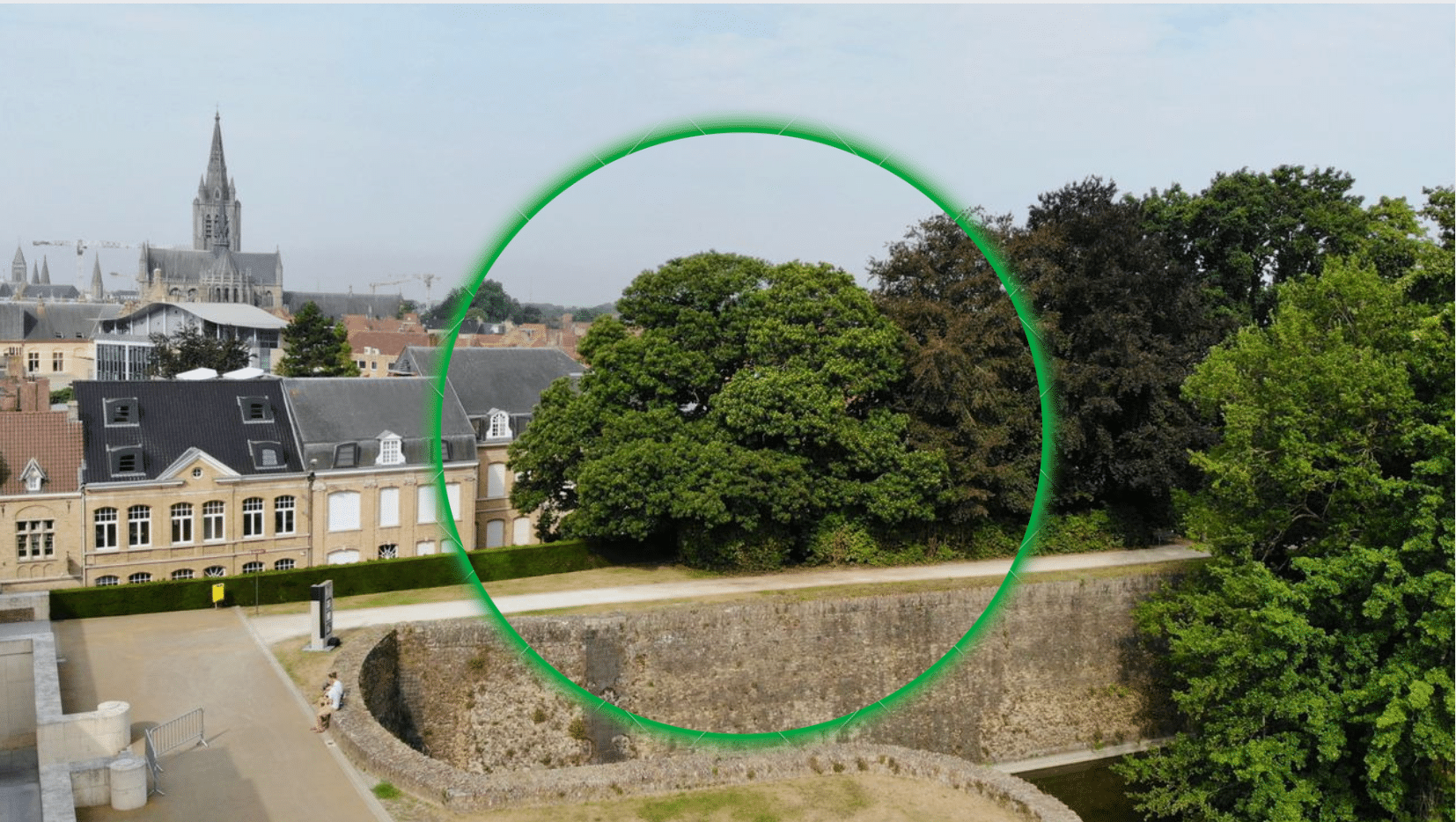

And there is a solitary tree that somehow managed to stay alive during four years of shelling. I found it eventually growing on the ramparts just north of the Menin Gate. The Chestnut tree was part of an avenue of trees planted on the ramparts in 1860. Every other tree died in the bombardment, or in the desperate search for fuel during World War Two. In 2020, it was voted Belgian tree of the year. ‘The Chestnut tree illustrates Ieper’s power to survive,’ explained the city environment councillor Valentijn Despeghel.

The Belgian tree of the year 2020 just after the First World War and today

The Belgian tree of the year 2020 just after the First World War and today© City of Ieper

With all the destruction in its history, Ypres has decided to call itself a city of peace. It has even developed a city logo

that features a red letter I (for Ieper) and the word Vredesstad (City of Peace). And they mean it. When Belgium’s War Heritage Institute announced plans to create a tank museum in a former barracks in Ypres, many local people were not thrilled. ‘Let us talk about the history, and the human suffering, and not the tanks,’ argued councillor Jan Breyne. But the first tank has already rolled into the city.

*

Ypres used to be a rather sad city to walk around. It could hardly be anything else. But it is slowly changing. It has several attractive squares like the Vismarkt where fish was sold, and the shady Veemarkt which was once a cattle market. You can easily find a stylish hotel, an interesting cafe or a lively music bar. Not far from the cloth hall, a coffee shop called ’t Binnenhuys occupies one of the few buildings that wasn’t totally destroyed. Dating back to 1772, the rambling mansion is now occupied by an interior design shop. The café takes up two small rooms at the back furnished with old leather sofas, antique lamps and faded photographs. Locals come here in the afternoon for coffee and cake sitting next to the old iron stove, or, if the weather is at all warm, sitting outside in the walled garden.

The city has a good number of bars where you can track down outstanding West Flanders beers like Westvleteren 12 and Omer. The Kaffee De 12 Apostels has a dark interior crammed with religious statues, paintings of Jesus and faded LP covers. It attracts a friendly mix of local musicians, teenagers drinking Mojitos and tourists who have strayed from the main square. Sometimes you might be lucky and hit the place on an evening when a folk band is on stage.

*

The tourist office has a new plan. It wants to encourage people to explore the landscape around Ypres. Before the war, this was a hilly region of castles, woods and fruit farms. But the war destroyed everything. ‘The Westhoek is a silent witness to what happened there in the First World War,’ explained Flemish tourism minister Zuhal Demir. She recently commissioned 25 small projects in 2023 to highlight the war landscape around Ypres.

From flat roads to steep hills, it is pleasant cycling in the region around Ypres.

From flat roads to steep hills, it is pleasant cycling in the region around Ypres.© Westtoer

Let’s take a look, I decided. I just had to rent a classic Belgian bike. And work out a route. The tourist office has mapped out several trails that roughly follow the front line. But you can easily create a customised route using the knooppunten network of numbered cycle points.

I set off down the Menin Road in the direction of knooppunt

32. It wasn’t long before I passed a war cemetery. Then another. And a third. There are more than 150 cemeteries around Ypres. Some are enormous, like Tyne Cot Cemetery, others are intimate burial grounds hidden in the woods. Each one is a unique experience.

Tyne Cot Cemetery in Zonnebeke, near Ypres. With nearly 12,000 buried soldiers, this memorial is the largest Commonwealth cemetery in the world, for any war.

Tyne Cot Cemetery in Zonnebeke, near Ypres. With nearly 12,000 buried soldiers, this memorial is the largest Commonwealth cemetery in the world, for any war.© Visit Flanders

The landscape has largely recovered from the war. But not entirely. I sat down under a tree in Bellewaerde wood to eat a tuna sandwich. Then I noticed an enormous crater created in 1915 by an underground mine explosion. And then I heard a scream. It came from the Bellewaerde theme park, built nearby on the site of a lost country house. But the sound felt as if it came from deep below the ground.

I had found the woods by following a trail that begins at the Hooge Crater Museum. The tourist office has created an information centre in a small building that was once the toilet block of the local school. It is one of three ‘entry points’ along the former front line that tell what happened during the war using photographs and film footage.

The Hooge Crater Museum in Zillebeke is a private museum about the First World War.

The Hooge Crater Museum in Zillebeke is a private museum about the First World War.© Visit Ieper

The trail led across the fields and around the woods. Along the way, I came across young trees that were recently planted at intervals along the former line of trenches. I slowly got to understand the landscape that shaped the course of the war. I saw the ridges that had to be captured. The gentle slopes where so many died for so little gain. The distant spires of Ypres that were slowly destroyed by shellfire.

I had planned a 25km cycle trip through the battlefields. It took in historic spots like Sanctuary Wood, Hill 60 and the Ypres-Comines Canal. On the way, I learned the story of a Canadian regiment that was almost wiped out on Frezenberg Ridge and read in a visitors’ book the names of three Canadian families that had visited during the past week. It struck me then that this war was long from being forgotten.

To the north of the former Ypres-Komen canal, in the provincial domain De Palingbeek, various landscapes can still be seen, which bear witness to the turbulent war years with their bomb and mine craters.

To the north of the former Ypres-Komen canal, in the provincial domain De Palingbeek, various landscapes can still be seen, which bear witness to the turbulent war years with their bomb and mine craters.© Visit Ieper

The route around the Salient takes in some beautiful spots, like the Palingbeek nature reserve and the Groenenburg woods. It is an enjoyable ride past farmhouses where you can stop for homemade ice cream, and spots where you can see the distant spires of Ypres. Back in the city, I followed a meandering trail around the ancient fortifications and stopped off at the café-restaurant Pacific Island. Located on an island that formed part of the 17th-century fortifications, it’s a friendly, relaxed spot on the water’s edge. A reminder that Ypres is more than just a destination for war tourists.

*

It was almost time. Every evening at just before 8 pm, a local police officer stops the cars on Menenstraat. Two local firemen raise their bugles to play the Last Post below the huge Menin Gate war memorial.

The sad military call known as the Last Post was first performed in Ypres by British buglers at the unveiling of the Menin Gate on 24 July 1927. The local police chief was so moved that he set up a committee to ensure it was played every day by local volunteer firemen.

The ceremony commemorates the 54,393 missing soldiers from the British Empire listed on the Menin Gate memorial. The firemen have played every day since 2 June 1928, more than 32,000 times, apart from the period under German Occupation, from 1940 to 1944. There is nothing like it anywhere in the world.

Every evening, at 8pm, a group of buglers sound the Last Post under the Menin Gate Memorial. The ceremony, founded in 1928, honours soldiers who fought and fell for the restoration of peace and the independence of Belgium.

Every evening, at 8pm, a group of buglers sound the Last Post under the Menin Gate Memorial. The ceremony, founded in 1928, honours soldiers who fought and fell for the restoration of peace and the independence of Belgium.© Visit Ieper / photo by Jan D'Hondt

Just a few hours after Polish troops liberated Ypres on 6 September 1944, Jozef Arfeuille grabbed his bugle and went to the Menin Gate with a group of friends. According to witnesses, he played the Last Post six times that evening to celebrate the liberation.

Sometimes, when it is raining, the buglers play to one or two tourists. Other nights, huge crowds gather under the gate. Important anniversaries can draw thousands of people. One hundred years after the end of the First World War, on 11 November 2018, some 10,000 people from across the world gathered to hear the Last Post.

Several years ago, I met some of the Ypres volunteer firemen in Brussels at a ceremony in the Canadian embassy. Their organisation, the Last Post Association, was being presented with a medal. The wives had come along. I asked one of the firemen if they ever talked about ending the ceremony. He shook his head. ‘It is our intention to go on for ever,’ he told me.

I realised then that Ypres is a special place. It is like nowhere else.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.