On a visit to the Flemish town of Lier, British journalist Derek Blyth discovers a wedding that changed history, the world’s most complex clock and some of life’s sweet pleasures.

How to translate Lierke Plezierke, I wondered, as I wandered through the little town of Lier. The sweet little pleasures of Lier, I thought might do.

I had come across the term in the reopened town museum where a large room is devoted to Lierke Plezierke. The displays included a cheerful collection of giants, a wall of folklore posters, and a local game called Struifvogelspel that involves hurling a wooden bird with a sharp beak at a target.

Since the 19th century, Lier has put on the St. Gummarus jubilee celebrations every 25 years. The highlight is the Lier Ommegang with the historical giants float.

Since the 19th century, Lier has put on the St. Gummarus jubilee celebrations every 25 years. The highlight is the Lier Ommegang with the historical giants float.© Visit Lier

The phrase Lierke Plezierke first appeared in the title of a 32-page pamphlet by the writer Felix Timmermans. In it, he described a folk procession organised in 1929 to celebrate a local couple’s wedding anniversary. The term was eventually taken up as Lier’s unofficial slogan.

The Sheep Heads Monument refers to the nickname of the inhabitants of Lier.

The Sheep Heads Monument refers to the nickname of the inhabitants of Lier.© Visit Lier

It’s a definite improvement on Schapenkoppen (Sheep heads), an insult that goes back to 1309. When Duke Jan the Second of Brabant wanted to thank the people of Lier for helping him win a battle, he said they could have a university or a market. They went for the market, and so Leuven got the university. Oh, die Schapenkoppen – Oh, those sheep heads, the duke sighed.

You might have thought that after more than seven hundred years the locals would want to forget the insult. But no, they have done the opposite, and embraced the sheep’s head. On a brief walk around town, I passed a sculpture showing a flock of sheep running down a hill, a sheep mural and a sheep head on a pedestal. Even more strange still, the town council recently decided to rebrand with a sheep’s head as its logo. Plezier op kop (a head for fun), is now Lier’s cheerful motto.

You get the message. Lier is a town that likes to enjoy life. Even the municipal website is a pleasure to explore with its cute graphic artwork that neatly captures Lier’s upbeat spirit. A recent campaign to promote a new bike-friendly policy is wittily illustrated with three cartoon elephants riding bicycles.

It’s easy to fall in love with this cheerful town with its meandering river, quiet lanes and friendly cafes. It welcomes tourists in a magnificent room inside the town hall decorated with a painted ceiling from the bishop’s palace in Antwerp.

Ceiling of the tourism office in the town hall

Ceiling of the tourism office in the town hall© Raymond Rottiers / Visit Lier

While it is sometimes called the Bruges of the Kempen, Lier doesn’t suffer from the modern hell of overtourism. Yes, you can do a boat tour, but it’s in a strange river barge with a net at the front once used for eel fishing. Yes, it has a beguinage, but the walled religious community is a hidden, sleepy neighbourhood of cobbled streets and houses with quirky names like De Gestolen Lieve Vrouw, The Stolen Madonna.

The beguinage in Lier has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.

The beguinage in Lier has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998.© Visit Lier

Nothing symbolises local pride more than the massive mammoth skeleton dug up in 1860.

The bones were long ago carted off to Brussels to be displayed in the Natural History Museum. But in 2018 the town commissioned Leuven-based tech firm Materialise to create a full-scale 3D printed replica. This unique structure is a highlight of the town museum.

Mammoth skeleton in the town museum

Mammoth skeleton in the town museum© Jeroen Broeckx / Visit Lier

*

As I sat on the slow train from Antwerp, I was expecting Lier to be one of those small Flemish towns where nothing ever happens. It lies somewhere off the main routes in rural Antwerp province. It doesn’t have a beautiful cathedral or a great art museum. And, of course, it doesn’t have a university. But then I was surprised by a sentence in Bart Van Loo’s book De Bourgondiërs (The Burgundians) where he describes ‘a forgotten day in Lier …when Western civilisation changed course.’

I must have read it wrong, I thought. It was more likely to be Lille. Or maybe Liège. But no. It happened in Lier on 20 October 1496. The young Joanna of Castile and Aragon had travelled to Lier to marry Philip the Handsome in an arranged marriage crafted to bring together the Burgundian Netherlands and Spain.

© Lier Archives

A fleet of 130 ships had set sail in July carrying 20,000 Spanish nobles, along with their wives, officials and servants. The ships were stocked with enough food and drink to last the two-month voyage, including 85,000 pounds of cooked meat, 1,000 chickens, 50,000 herring and 400 vats of wine.

The couple were due to marry in Lier in a spectacular ceremony. But they fell in love the moment they met, despite the awkward silence as they didn’t have a word in common. The royal couple tracked down a local priest who agreed to marry them in a nearby house and they then spent the night together before emerging the next day for the official wedding.

A large crowd had gathered on a nearby wooden bridge to watch the romantic wedding. Too many people, it turned out. The bridge collapsed, plunging dozens of sheep heads into the River Nete.

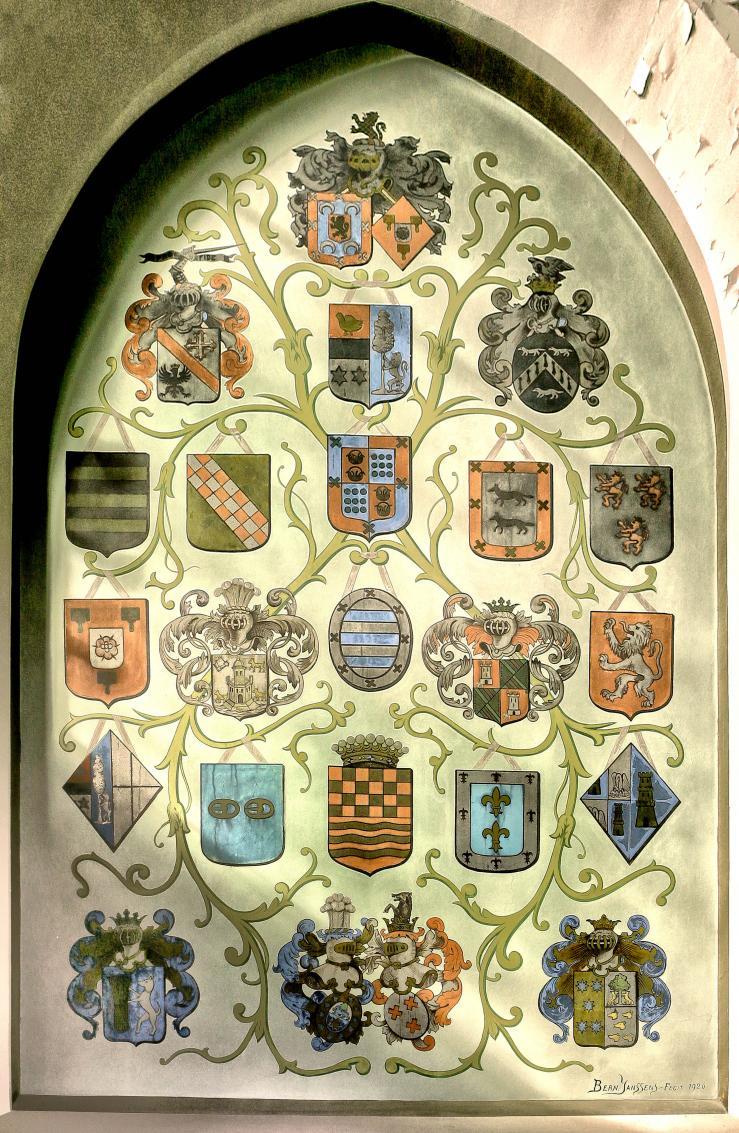

Coats of arms of the Spanish governors inside the St Jacob's Chapel or Spanish Chapel

Coats of arms of the Spanish governors inside the St Jacob's Chapel or Spanish Chapel© Mon Rottiers / Visit Lier

The tourist office has produced an online walking trail that takes you to some of the spots linked to this fabulous wedding. There is even a version for Spanish-speaking tourists who want to know about the young Joanna (before she became Joanna the Mad).

The walk begins in a Spanish chapel that once welcomed pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostella. Then you are taken to look at the bridge that collapsed in 1496, or at least the reconstructed version. There is a hotel near the bridge called Hof van Aragon that stands on the site of the religious building where the royal couple spent their first night together. It is still popular with honeymoon couples.

The walk also guides you to the St Gummarus Church (nicknamed De Pepperpot because of its odd tower) where the couple officially married. The delicate Brabant Gothic church (currently closed for renovation) is dedicated to a local saint who tied his belt around a fallen tree that had split in two, restoring it to life. He became famous for healing almost anything, from broken bones to broken marriages. He also helped childless couples, the deaf and dumb, woodcutters, lumberjacks and glovemakers.

The St Gummarus Church is dedicated to a local saint who was famous for his healing skills.

The St Gummarus Church is dedicated to a local saint who was famous for his healing skills.© Visit Lier

The versatile Gummarus turns up again on another walking tour. This one (available in Danish) takes in places with a link to Scandinavia. It tells the story of Viking raiders, a Danish king exiled in Lier, and the last Catholic archbishop of Norway, who also ended up here. But the Scandinavians didn’t always get a warm welcome. A 17th-century painting in a small chapel reveals how Gummarus inflicted a horrific punishment on the Vikings after they murdered a priest.

I was about to set off a third walk dedicated to the war years. But then I noticed the time. I had an appointment that couldn’t wait.

*

A small crowd had gathered in front of the Zimmertoren, a mediaeval stone tower. They had come to watch a mechanical clock that performs every day at twelve on the dot. The Jubelklok, or Jubilee Clock, was constructed by Lodewijk Zimmer, a local watchmaker and amateur astronomer. He took over the abandoned 14th-century tower to display his astronomical clock. It is a fabulous construction that incorporates two globes decorated in blue and gold, along with ten clock faces that indicate signs of the zodiac, tides in Lier, phases of the moon, days of the month, months of the year and other arcane natural cycles.

Local watchmaker Lodewijk Zimmer constructed an astronomical clock in an abandoned 14th-century tower, now known as the Zimmer Tower.

Local watchmaker Lodewijk Zimmer constructed an astronomical clock in an abandoned 14th-century tower, now known as the Zimmer Tower.© Visit Lier

The clock chimed gently at noon as four mechanical figures struck the bells. The figures represent fictional characters and writers chosen to symbolise the four ages of man. After a pause, two red shutters flipped open, revealing the dates 1830-1930. Then a portrait appeared. ‘That’s the first burgomaster of Lier,’ a father told his daughter.

‘No, it’s not,’ his wife said, a little sharply. ‘It’s the first king. Leopold.’

Another portrait appears. ‘And that’s the second king,’ the wife explained in the manner of a strict schoolteacher.

‘He looks more like a burgomaster,’ the husband insisted.

‘It’s Leopold the Second,’ the wife said. ‘And that’s Albert,’ she stated as the third figure appeared.

‘And so is that Leopold the Third?” the husband asked, when the next figure showed up.

‘It can’t be,’ the wife stressed, firmly. ‘The clock was made in 1930 to mark the one hundred anniversary of the Belgian revolution. And Albert reigned until 1934.’

‘So this one is a burgomaster.’

‘Yes, and so is the next one.’

I watched the slow procession of solemn and bearded sheep heads. And then the flaps suddenly slammed shut. It was all over for another day.

Most people walked away, looking for a restaurant no doubt, but I wanted to visit the Zimmer Museum next to the tower. The highlight is the Wonder Clock that Zimmer exhibited in 1935 in Brussels and four years later at New York’s World Fair. It’s not really a clock. More like some weird contraption in an early science fiction movie. It took Zimmer three years to build it in his workshop. It was admired by Albert Einstein, and described by the New York Museum of Science as ‘the outstanding wonder of the age’. Now it belongs to Lier.

The Wonder Clock was admired by Albert Einstein.

The Wonder Clock was admired by Albert Einstein.© Visit Lier

The clock incorporates 93 small dials that display time divisions of the world, movements of the planets, high and low tides in the world’s principal ports and dozens of other details. One clock face marked with Chinese characters adds to the general sense of disorientation by running anticlockwise.

Zimmer even added a dial that gives the date according to the abandoned Cotsworth calendar. Invented in 1931, it divided the year into 13 months of 28 days. But it was a flop, unlike the Gregorian calendar imposed upon mainland Europe in the 16th century and represented by another dial. There is also a decimal clock based on an abandoned timekeeping system that used 100-minute hours and ten-hour days.

Louis Zimmer (1888-1970) in his workshop

Louis Zimmer (1888-1970) in his workshop© famousbelgians.net

Every hour, on the hour, the clock chimes. And then you are treated to a strange mechanical demonstration involving seven tiny spinning dancers in swimming costumes and a miniature man wearing hiking shorts. As the dancers rise and fall to represent the position of the planets, the hiker stands on a set of scales that indicate his weight on different planets – 70 kilos on earth becomes 177 kilos on Jupiter. At which point, a dancer shoots up in the air to symbolise weight gain.

Zimmer added two more dials that reveal his astonishing skill as a clockmaker. The fastest clock has a hand that revolves once around the dial in one-hundredth of a second, while the slowest rotates once every 25,800 years to represent the precession of the Earth’s axis. The museum claims it is the slowest moving mechanism in the world.

There is more to admire when you climb the ancient stone tower next to the museum. Up in the rafters, Zimmer installed the complex mechanism to control his Jubilee Clock. A stern notice warns visitors to keep well clear when the bells are about to strike.

Despite his fame, Zimmer spent his entire life in Lier

Despite his fame, Zimmer spent his entire life in Lier. And he died in the house where he was born. I set off to find it, expecting something impressive. He was a celebrity clockmaker after all. But the house is tiny. This can’t be it, I thought, until I read the name ‘L. Zimmer-Dirckx’ above the door.

Looming over the narrow front door, a huge 18th-century religious shrine. Next door, an abandoned house waits to be turned into luxury apartments. It was hard to believe that Zimmer sold his clocks in the tiny ground-floor shop and created his fabulous timepieces in a workshop at the back.

*

Lier’s Four-Leaf Clover

Lier’s Four-Leaf CloverSome years ago, Lier tried to forge an identity by promoting its four most famous residents. They were called het Klavertje Vier van Lier – Lier’s Four-Leaf Clover. Louis Zimmer was an obvious candidate. And Felix Timmermans also made the list, along with Isidore Opsomer (an artist) and Louis Van Boeckel (a blacksmith). No women, you might complain. And why the blacksmith?

I already knew about Zimmer, but I wanted to know more about Felix Timmermans. He has a square named after him, as well as a bronze bust placed next to the pretty little river that runs through Lier. The sculptor shows him dressed in a suit and tie, with a wild crop of hair parted in the middle. I was reminded of Dylan Thomas in his handsome youth.

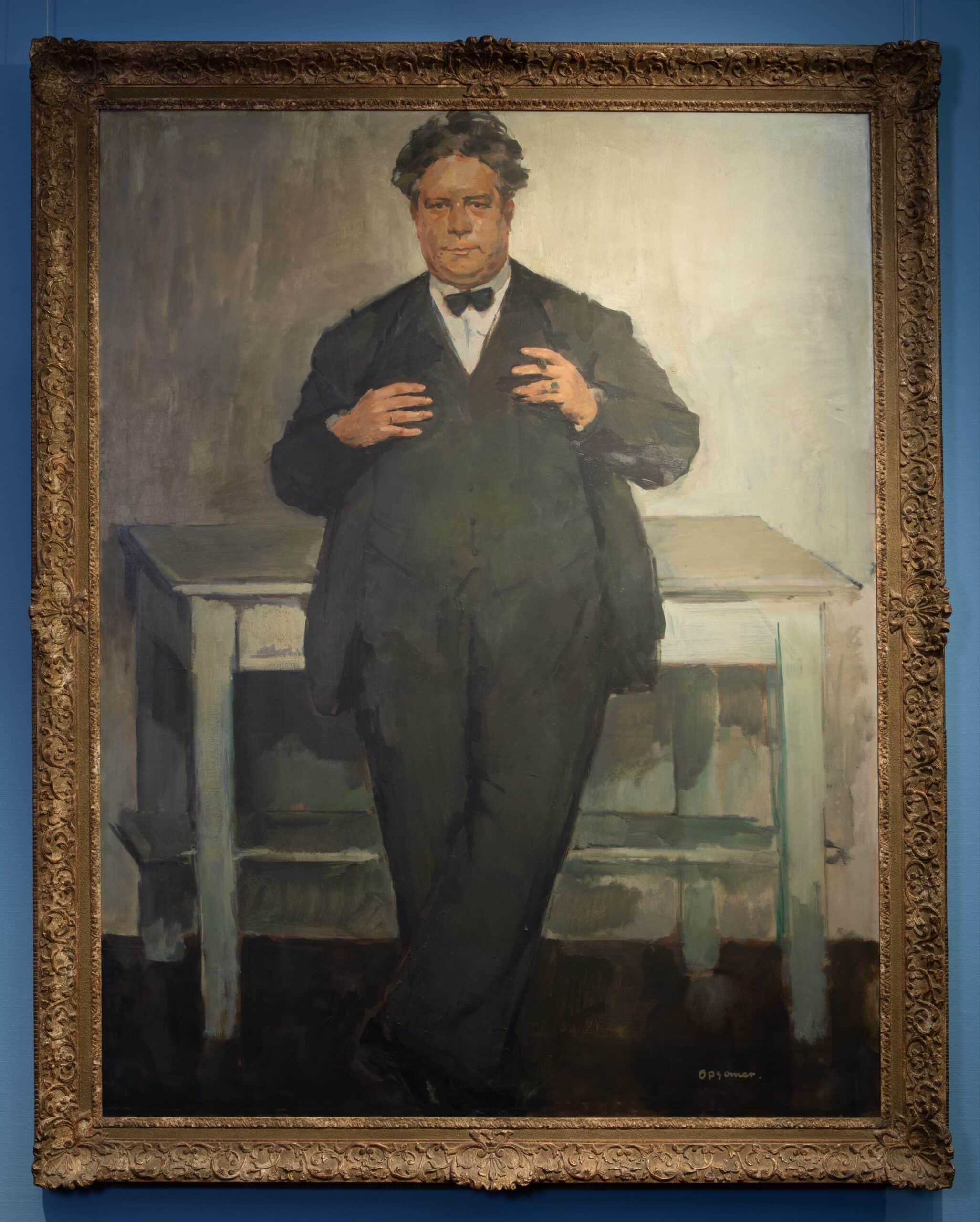

The town used to have a museum, the Timmermans-Opsomerhuis, but the museum had closed down and the collection moved to the city museum. This is where you have to go to admire works by the local artist Isidore Opsomer, including his astonishing portrait of Felix Timmermans, which shows the oversized writer barely fitting in the picture frame.

Portrait of the writer Felix Timmermans by local artist Isidore Opsomer

Portrait of the writer Felix Timmermans by local artist Isidore Opsomer© Visit Lier

The museum also displays a charming series of paintings by Timmermans inspired by the Flemish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Timmermans is credited with inventing the romantic image of Bruegel as a painter of Flemish rural life. The museum has the good luck to have its own Bruegel, although it is a copy by the artist’s eldest son Pieter of his father’s famous ‘Dutch Proverbs’.

And what about the blacksmith? The fourth important figure in the history of Lier. Louis Van Boeckel. His bust stands on a pedestal in the city park. With his long hair and thick moustache, he looks a bit like Gerard Depardieu in the Asterix films.

Bust of Louis Van Boeckel

Bust of Louis Van Boeckel© Visit Lier

Now almost forgotten, Louis Van Boeckel was quite a celebrity in his day. A blacksmith by trade, he was famous for his elegant wrought iron decoration. After he won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris World Fair, his studio in Lier was inundated with commissions from all over the world. He supplied ornamental ironwork for the grave of Czar Alexander III in St Petersburg, the National Bank in Athens and the Cathedral in Buenos Aires. He is also credited with creating an ornamental iron fence to surround the White House in Washington. But it is now concealed behind a ring of more modern, less elegant, security fences.

A blacksmith by trade, Louis Van Boeckel was famous for his elegant wrought iron decoration

The blacksmith workshop where Van Boeckel worked has gone. A sign on a modest house near the Hof van Aragon marks his former home. It used to have an ornate iron bell pull in the shape of a small tree branch to impress visitors. One guest wrote in 1907 that Van Boeckel’s handshake made ‘the visitor feel that he is grasping the only hand in the world that can transform a piece of scrap iron into an art object the equal of any a jeweller has ever produced.’

Town hall of Lier

Town hall of Lier© Visit Lier

Van Boeckel has left behind some examples of his work in Lier. The beautiful railings in front of the town hall were created in his studio in the late 19th century. He also shaped the elaborate ironwork on the bank building at Grote Markt 3. You might also spot a garland on a monument or some other detail he produced.

The Lier Four belong to the past. But other remarkable people have been born in Lier. More than you might expect for a modest town of 36,000 sheep heads. The list includes former prime minister Gaston Eyskens, singer Eva de Roovere and tennis star Yanina Wickmayer. The Belgian rock band Triggerfinger also emerged in Lier back in the 1980s.

The Hof van Ringen, the home of fashion designer Dries Van Noten, on the edge of town

The Hof van Ringen, the home of fashion designer Dries Van Noten, on the edge of town© Visit Lier

You might also want to add the reclusive fashion designer Dries Van Noten who lives in the impressive Hof van Ringen on the edge of town. With the help of interior designer Gert Voorjans, Van Noten has created a little palace filled with colourful fabrics and antiques, along with a sumptuous garden where he can retreat from the pressures of the fashion business.

Van Noten brought a hint of high fashion to Lier in 2015 when he designed costumes for the town’s historical St Gummarus procession. Dating from 1417, the annual procession features a horse dressed by the Flemish designer in a costume of expensive Italian leather and Indian silk.

The street artist Joachim has livened up some of the town’s neighbourhoods with his murals.

The street artist Joachim has livened up some of the town’s neighbourhoods with his murals.© Visit Lier

One more name needs to be added to the list of Lier celebrities. The street artist Joachim has livened up some of the town’s neighbourhoods with his murals. ‘I found that Lier was missing something contemporary, an urban feel,’ he explained in an interview. Joachim launched a street art project in 2015 titled Lier UP which has resulted in bright, fun street art on blank walls. One of his works represents characters from a Felix Timmermans’ novel. Another of his creations features sheep heads. Oh please, not more sheep, I am thinking.

Mural by Joachim

Mural by Joachim© Visit Lier

*

‘You need to read Pallieter, if you want to understand Lier,’ my Flemish friend had advised. Hermann Hesse and John Muir were fans of the book. So was the poet Rainer Maria Rilke. ‘Read it,’ Rilke urged. ‘You will laugh. And you will cry as well.’

Published in 1916, Timmermans’ gentle rural tale tells the story of a young man with an enormous appetite for life. The novel portrayed Lier as a town where people knew how to have a good time. It was, Timmermans once said, the promised land. Ei, het is hier schooner dan schoon – ‘My, it’s impossibly beautiful here,’ he exclaimed.

People loved the book. It was the most popular Flemish novel of the 20th century. The word Pallieter entered the Dutch language – een levenslustige kerel, is how the Van Dale dictionary defines it. A guy with a lust for life, you might say.

Statue of Pallieter looking at the sky

Statue of Pallieter looking at the sky© Visit Lier

The novel included a notorious scene in which Pallieter rescues a naked girl from a pond and carries her off on his horse. The Catholic church did not approve. Timmermans hastily deleted the scene to avoid his novel landing on the index of prohibited books. But morals have changed and there is now a bronze statue on the edge of town that illustrates the forbidden episode.

I set off to look at the cafe in the Begijnhofstraat where Timmermans found inspiration for his characters. The name Het Belofte Land (The Promised Land) is written on the front of the building in large red letters. A relief above the door depicts two men carrying a huge bunch of grapes. But the curtains were pulled shut. The Promised Land had shut down.

The image of the two carrying men was also used by Timmermans as a cover image for the first edition of 'Pallieter'.

The image of the two carrying men was also used by Timmermans as a cover image for the first edition of 'Pallieter'.© Wikipedia

All over town, you find references to Pallieter: there is a Pallieter park, as well as a Pallieter travel agency and a Pallieter jogging group. There is even a Pallieterplekken map that takes you to 25 spots selected by local people as their Pallieter spots. It is a fascinating way to discover some hidden places, like the kiosk in a park where kids hang out after school and a bench on the river where locals like to sit eating fries.

You are also offered a cycle route called Pallieteren langs de Nete, which takes you out into a peaceful rural landscape formed by the meandering rivers Grote and Kleine Nete. And on the way back you can stop for fries at the Pallieter frituur.

The landscape around the River Nete in Lier forms the backdrop for the novel 'Pallieter'.

The landscape around the River Nete in Lier forms the backdrop for the novel 'Pallieter'.© Visit Lier

Before leaving Lier, I had one little pleasure still to experience. ‘You have to try a Liers Vlaaike,’ my friend insisted. She sent a text message with an address.

The famous Lier tarts were invented in the 19th century by a local baker whose shop stood on the corner of the Grote Markt. Once a closely guarded secret, the recipe is now known to involve a blend of cinnamon, coriander, cloves and candy syrup.

The famous Lier tarts 'Lierse Vlaaikes'

The famous Lier tarts 'Lierse Vlaaikes'© Visit Lier

I eventually found the shop near the Zimmertoren that sold authentic Liers Vlaaike. And then I tried to think of a Pallieterplek, a pleasure spot, where I could sit down to eat the local treat. I remembered the bridge across the little River Nete next to the Hof van Aragon. What could be more Pallieter than this achingly romantic spot shaded by old trees?

I sat down and took a bite of the little Lier cake. ‘It’s the perfect combination of hard crust and soft interior,’ my friend had said. It set me off thinking again about Lierke Plezierkes. Those sweet little pleasures of Lier. I was beginning to understand what they meant.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.